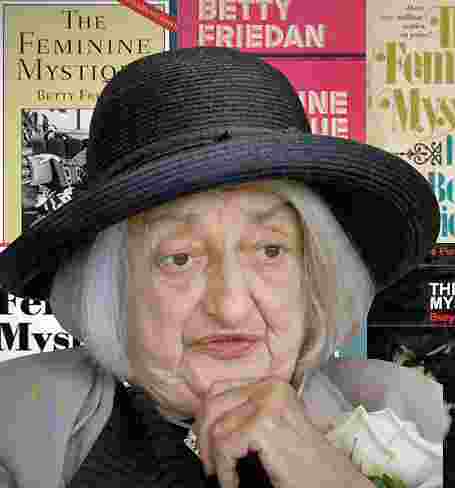

This Labor Day during the 50th anniversary year of the publication of the landmark “Feminine Mystique” by Peoria native Betty Friedan, one wonders, “What if?”

This Labor Day during the 50th anniversary year of the publication of the landmark “Feminine Mystique” by Peoria native Betty Friedan, one wonders, “What if?”

What if more people knew of Friedan’s background – especially her years as a labor journalist during the Red Scares of post-war America?

Few realize that Friedan, born Bettye Naomi Goldstein at Proctor Hospital on Feb. 4, 1921, was not only a student reporter and editor at Peoria (Central) High School and Smith College, but an advocacy journalist covering equal rights for working women and various progressive issues for years before “Feminine Mystique.”

From 1942 into 1952, Friedan was a reporter for Federated Press, which provided stories to labor unions and other clients. Then she was a staffer for seven years at UE News, a publication of the United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers of America (UE).

“It was a loss to American history that a remarkable journalist and feminist leader failed to bring forward the seminal contributions that labor ideals and struggles had made to feminism in the 20th century,” wrote James Lerner, former UE News editor, in his book “Course of Action: A Journalist’s Account from Inside the American League Against War and Fascism and the United Electrical Workers Union (UE), 1933-1978.”

Now recalled mostly as author of “The Feminine Mystique,” about the unfulfilled lives suburban women faced, and a few other titles – plus as the first president of the National Organization for Women (NOW) as a leader in the unsuccessful push for an Equal Rights Amendment, Friedan grew up in Peoria, the daughter of Harry and Miriam (Horwitz) Goldstein. Harry owned a jewelry store in Peoria, and Miriam was a journalist for a Peoria newspaper until they were married.

After graduating from the all-female Smith, Friedan studied for a year at the University of California/Berkeley, then declined an offer to remain there in order to work as a journalist in the labor movement. That led her to working with Lerner at UE.

A “memorable associate I worked alongside in my early years with UE News was Betty Goldstein, later well known as Betty Friedan,” Lernrer wrote. “At the height of the union’s growth during the war, UE News was putting out a 12-page weekly tabloid with a circulation of about half a million copies.”

The UE was the most progressive – some said “radical” – labor union in the nation, and, as such, was accused of being led by communists, a charge that was exaggerated but not altogether false.

“Goldstein and I frequently covered stories of broad national interest to union members, including equal rights for women in the workforce,” Lerner wrote. “She wrote a number of important articles on women’s wages, among them several pieces on wage discrimination against women in the electrical industry.”

In 1947, Goldstein married ex-GI Carl Friedan, who’d work public relations and advertising. Betty Friedan (she’d dropped the “e” from her first name) took maternity leave in 1949 to give birth to their first child, then returned to UE News to work three more years.

At Federated and UE, Friedan wrote articles about rank and file union members, workers in general and minorities, and she criticized conservative interests that she saw as undermining reform and progressive causes.

In 1943, she blasted a business agenda supported by the National Association of Manufacturers to weaken labor, reverse the New Deal, and let businesses operate however they pleased, all to boost profits.

One of her best pieces of journalism at UE was a 1952 pamphlet, “UE Fights for Women Workers,” outlining the exploitation of working women. In it, she foreshadowed ground she’d cover in “Feminine Mystique,” describing advertisements that show women working in GE kitchens, watching Sylvania TVs or using Westinghouse Laundromats: “Nothing is too good for her,” Friedan wrote, “– unless she works at GE, Westinghouse or Sylvania, or thousands of other corporations.”

Describing physical woes caused by factory speedups, the typical less-pay-for-equal-work and the glass ceiling shutting off promotions to better-paying jobs, the uncredited Friedan earned praise for the 39-page analysis. Historian Lisa Kannenberg, unaware of the identity of the pamphlet’s author, in 1990 said it was “a remarkable manual for fighting wage discrimination that is, ironically, as relevant today as it was in 1952.”

Ending with a 10-point program for women’s rights in the electrical industry, which included access to all skilled jobs and pay equity, the pamphlet’s recommendations were adopted at UE’s 17th convention.

“For Friedan herself, the fight for justice for women was inseparable from the more general struggle to secure rights for African Americans and workers,” wrote biographer Daniel Horowitz.

Why is that not better known?

Blame Joe McCarthy.

An onslaught of anticommunist attacks on unions by the House Un-American Activities Committee and the McCarthy Senate hearings in the late 1940s and early ’50s – plus a clause in 1947’s Taft-Hartley Act requiring union officers to sign an anti-communist affidavit – greatly weakened the UE. Its membership topped 600,000 in 1946, but by 1950 was down to 71,000, and that decline eventually forced cutbacks that resulted in Friedan’s layoff.

Further, Friedan was understandably fearful of tying her rising star in the ’60s to those dark days. Anticommunism was still being used to attack the Civil Rights, anti-war and student movements and, as Horowitz noted, “Had Friedan revealed all in the mid-1960s, she would have undercut her book’s impact, subjected herself to palpable dangers, and jeopardized the feminist movement.”

There may have been local memories that triggered concern, too, Horowitz added.

“Peoria also had a history of conflict between workers and corporations, which erupted with considerable force during Goldstein’s last two years in high school,” he wrote. “Reactionaries in the city made the absurd claim that there were 15,000 communists. In the summer between Bettye’s junior and senior years, the Peoria Journal-Transcript discharged three members of The Newspaper Guild.”

Unfortunately, had the public realized the ties between Friedan’s early work as a labor journalist and her later feminist writing and activism, there may have been a better understanding of the solidarity of those movements, and better outcomes to derailed or defeated campaigns as different (yet connected) as the Equal Rights Amendment and the Employee Free Choice Act.

2 comments for “The full story on Peoria’s Betty Friedan”