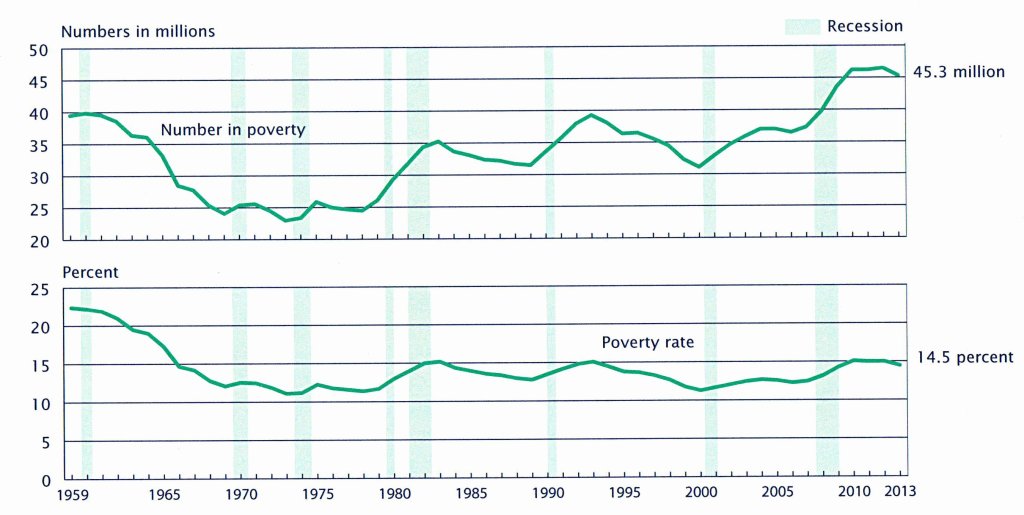

Americans in poverty and U.S. poverty rate, 1959-2013 SOURCE: U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population survey, 1960-2014 Annual Social and Economic Supplements

As winter temperatures drop, homeless people may be more visible, either scrambling on the streets to find emergency shelter or seeking momentary refuge in public spaces like libraries.

Homelessness and the poverty that can drive it continue. In a 2014 report, the U.S. Census Bureau said:

* The official poverty rate was 14.5 percent, with 45.3 million people living in poverty. “For the third consecutive year, the number of people in poverty at the national level was not statistically different from the previous year’s estimate,” the Bureau said.

* The 14.5 percent rate was 2 percentage points higher than in 2007, the year the Great Recession started.

* The poverty rate for children younger than 18 was 19.9 percent in 2013, for people 18-64 13.6 percent, and for people 65 and older 9.5 percent.

* More than 578,000 people are homeless in America, according to a recent count by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD).

In Peoria, “poverty has increased. Homelessness continues to rise as well,” said Don Johnson, vice president for community investment at the Heart of Illinois United Way, which funds more than $300,000 in competitive grants to help with issues surrounding homelessness, such as food and shelter.

“We went from 304 cases in 2011 to 370 last year,” he said.

Kristy Schofield, director of homeless & housing at Dream Center Peoria downtown agreed.

“Last year in our emergency overnight shelter we served 365 individuals and families,” she said. “This year [2014] we have served over 400 already. So I have seen an increase.”

Given Peoria’s population of about 116,000, that means the “homeless rate” is about 34 per 10,000 people. That compares to bigger cities, such as Boston (25/10,000) and Jacksonville, Fla. (33/10,000), according to the National Alliance to End Homelessness.

There are 316 emergency beds in Peoria, advocates say.

“We have 65 emergency overnight beds in the [Dream Center] shelter,” Schofield said. “We have 21 apartments in the transitional housing program serving homeless women, children and families in a two-year program. The transitional program is always full with a long waiting list.”

Various local agencies help alleviate the effects of poverty, from the Dream Center and the Peoria Rescue Mission to Friendship House and Neighborhood House, the South Side Mission and the South Side Office of Concern, plus the Salvation Army, Common Place and more. Many get some funds through HUD’s Continuum of Care program.

“We receive city, state and federal funding as well as private donations to keep us serving those in poverty,” Schofield said. “We never have all the funding we need.

“The biggest difference this year in the homeless world as compared to last is that last year most came to us unemployed,” she continued, “while this year I have many more that have jobs – they are just under-employed.”

The causes of homelessness include a lack of jobs that pay enough to make available housing affordable; a shortage of such housing; mental, physical and financial problems ranging from psychological disorders to divorce; and poverty, period.

Indeed, it may seem that in the long War on Poverty, the nation lost. Nevertheless, government programs have proven effective – especially after 1964’s Economic Opportunity Act, which until 1980 made dramatic gains in alleviating poverty. (See chart.) A 2014 study for the National Bureau of Economic Research, “Waging War on Poverty: Historical Trends in Poverty Using the Supplemental Poverty Measure,” showed the effectiveness of government anti-poverty policies. Further, research by the U.S. Department of Commerce and the Census Bureau, said, “Government household resources such as the Earned Income Tax Credit and SNAP [food stamps] lifted nearly 2 percent of recipients out of poverty.

“Without government programs, poverty would have risen from 31 percent, while with government benefits poverty has fallen,” it added.

However, dealing with homelessness has been such a struggle that some areas are resorting to other responses. According to “No Safe Place,” a study by the National Law Center on Homelessness and Poverty (NLCHP), homeless people are increasingly punished despite poverty limiting victims’ alternatives.

“The contemporary way to criminalize homelessness was established in the 1990s in New York and San Francisco, where advisers pressed the city to clear out street people for fear they’d deter developers’ investments,” reported journalist Aaron Cantu.

Criminalizing homelessness or poverty is reminiscent of the comment from 19th century journalist and author Anatole France, who said, “The law in its majestic equality forbids the rich as well as the poor to sleep under bridges, to beg in the streets, and to steal bread.”

At least 21 U.S. communities have passed measures targeting homeless people and those who try to help them, according to the National Coalition for the Homeless (NCH), which in a new study documented cities’ bans on feeding the homeless, sleeping on sidewalks or in cars, even lining up for soup kitchens.

Cities are “criminalizing being homeless or helping the homeless,” said NCH’s Michael Stoops. “Cities’ hope is that restricting sharing of food will somehow make [the] homeless disappear and go away. Even if these ordinances are adopted, it’s not going to get rid of homelessness.”

The NLCHP lists other ordinance violations – sleeping or “camping” in public; begging in public; loitering, loafing and vagrancy; sitting or lying down in public – and concludes that such criminalization “violates the civil and human rights of homeless people.”

In the Midwest, for instance, Davenport, Iowa, words its sleeping restrictions a “misuse of park property.” Evanston, Ill., has bans on panhandling, loitering and, through “health and sanitary provisions,” sleeping in public. South Bend, Ind., also prohibits panhandling, plus loitering at bus or railroad stations, all according to NCH’s report “A Dream Denied: The Criminalization of Homelessness in U.S. Cities.”

But in Peoria, the City has not targeted homeless citizens, according to Peoria’s Corporation Counsel Don Leist, who said “We try to handle ‘aggressive panhandling’ and loitering – especially in the context of gang activity – but that’s about it. If we choose to, we could enforce the law about obstructing the public way, but that’s very rare.”

Such ordinances and the law enforcement approach are expensive, which leads to a solution that may seem obvious; housing. Salt Lake City had been spending about $20,000 per homeless resident per year – paying for policing, arrests, jail time, shelter and emergency services. Homelessness didn’t fall, so for $7,800 a year through a new program, Housing First, Salt Lake City started providing people with apartments and case management services, and chronic homelessness declined more than 70 percent.

Meanwhile, there’s some concern about the stability of the government safety net that can help.

“It will be interesting to see what happens t federal funds over the next 18 months due to the changes happening in Washington, D.C.,” said Johnson, from the United Way. “I think public perception has changed over the past 10 years. Funders want to see more outcomes to help individuals/families become self sufficient.”

2 comments for “Poverty and homelessness up, but not ‘criminalized’ here”