Contamination at this Ottawa site comes from sources including radium-bearing materials from the Radium Dial Co. that produced watch dials that glowed in the dark from radioactive substances added to paint. Workers there became known as the Radium Girls as they slowly and painfully died of cancer. (Photo by Illinois Geological Survey)

A year ago this month, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Scott Pruitt, appointed by President Donald Trump, visited the USS Lead Superfund site outside Chicago. It’s still hazardous.

The EPA’s Superfund program was established 38 years ago to clean up land contaminated by hazardous waste posing risks to people and/or the environment.

Pruitt has said he supports Superfund efforts, but EPA staff has fallen to 14,162 nationwide, the lowest in decades, and funding has declined, according to the U.S. Government Accountability Office. The GAO reported, “Annual federal appropriations to the EPA Superfund program generally declined from about $2 billion to about $1.1 billion in constant 2013 dollars from fiscal years 1999 through 2013.”

Independent consultant Kate Probst, who’s studied Superfund for decades, told National Public Radio. “They don’t have the money to clean up an average Superfund site in most states. They just don’t have $25 million.”

It’s getting worse. Trump’s proposed budget for fiscal year 2018 asks Congress to cut Superfund appropriations 25 percent more, plus an additional 36-percent cut to a separate program for cleaning up contaminated former industrial sites.

“Funding is the most significant driver of sites not getting cleaned up,” Nancy Loeb, director of the Environmental Advocacy Center at Northwestern University’s Pritzker School of Law told The New Republic.

Nevertheless, last summer Pruitt said he’d come up with a “10 Most Wanted” priority list from the country’s 1,300-plus Superfund sites for aggressive attention. However, the EPA already has a National Priority List (NPL) of sites eligible for long-term remediation financed through Superfund, and the problem is so serious that Pruitt was forced to list 21 places destined for “immediate and intense action.”

Plus, the EPA itself conceded there’s no money available to deal with them, stating in December, “There is no commitment of additional funding associated with a site’s inclusion on the list.”

Further, the NPL has more than 1,100 sites, with dozens in Illinois.

“Hazardous substances are buried/stored in the area, but they also continue to be generated (and then need to be managed), so this is something everyone should be concerned about,” says Lisa Offutt of Peoria Families Against Toxic Waste. “It’s a real danger. But for the last year, so many things we rely on for a decent quality of life – health care, human rights, civil rights, basic physical safety, etc. – have been under attack, I think it’s hard to focus on one thing.

“Caps over disposal sites can be compromised, allowing rainwater to leach through the waste and into the groundwater (this has already happened [at US Ecology] in Sheffield,)” she continues. “All landfills will eventually leak, but if you have a low-quality cap and no liner, that leak will probably happen sooner rather than later. And monitoring systems may or may not be adequate to detect what is actually happening underground.”

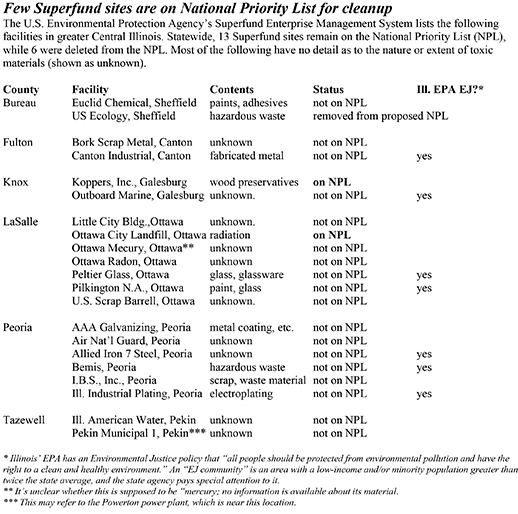

Besides the NPL, the EPA maintains a Superfund Enterprise Management System (SEMS), which lists some sites that aren’t on, or have been dropped from, the NPL. (See box.)

Illinois’ EPA – which does more than deal with leaking underground storage tanks and used tires – tries to cope where feds have failed. For example, the 65-acre US Ecology dirt-trench dump site outside Sheffield, containing some 4 million cubic feet of contaminants including radioactive carbon-14 and tritium was abandoned in 1979 despite higher-than-natural levels of tritium found to be moving about 500 feet a day, 600 times predicted speeds. The state of Illinois has been liable for the site for 20 years.

“[An IEPA] report confirmed that the trenches the radioactive waste is buried in are unlined,” Offutt says. “The site may be closed, but the fact remains that a variety of chemical and radioactive waste is sitting in unlined pits where it can leach into streams and groundwater. It reminds me of the unlined barrel trench at Peoria Disposal Company #1 here in Peoria (where we have reason to believe 55-gallon drums filled with PCBs are corroding away to leak into the aquifer and/or Kickapoo Creek.”

Meanwhile, Trump’s EPA appointments are dominated by industry figures and political allies, highlighted last month, when Dow Chemical corporate attorney Peter Wright was nominated to be EPA’s assistant administrator for Land and Emergency Management, which supervises emergency responses to cleanups at toxic sites.

Elsewhere, the independent EPA Advisory Board was disbanded, and Pruitt said his agenda includes:

- replacing carbon and clean-water regulations,

- convening a “national debate” on whether climate change is real (commenting to Reuters, “How do we know what the ideal surface temperature is in 2100?”)

- reconsidering rules he sees as “too broad” or harmful to business,

- reforming the biofuels policy in the Renewable Fuel Standard Act pass in the George W. Bush administration to help farmers with corn-derived ethanol

- reviewing vehicle fuel-efficiency rules

“The EPA can only enforce existing regulations (a song we heard many times while working against the expansion of PDC #1),” says Offutt. “So as long as you have someone like Trump in office and Pruitt heading up the agency, the regulations are going to be even less protective. Add to that a level of staffing that prevents timely inspections and a backlog of permit renewals, and ultimately many of us haven’t felt protected for a while. The current administration is not going to reverse that trend.”

Republican William Ruckelhaus, the first head of the EPA in 1970, has said, “One of the tragedies of this administration’s approach is that it is just enhancing mistrust of what government is doing.”