PAUL KRAINAK

Local artists are generally poised between the rural and the urban, craft and fine art, and often straddle two-or-more time frames. That may often be true of artists who live on the coasts but their societies are overwhelmed by institutions that manage art as a commodity and regard artists as the fruits of their transnational conventions. In the Midwest, the main constituents for local artists are university art departments, who balance tradition with experimentalism, and a community of peers that respect many domains of design and manufacture. The significance of such traditions often stand in for the relative absence of criticism and patronage.

Michael Paxton’s 1980’s performance recitations, a textured overlay of sound poetry, and trance-chanting, are links between so-called naïve art and the avant-garde. His desire to establish some fabric of Appalachian culture on a plane with contemporary urban aestheticism surfaces now as rock-hard abstraction. The new works are ethnographic impressions of a long, evolved body of work –– a secular spirituality frozen in paint.

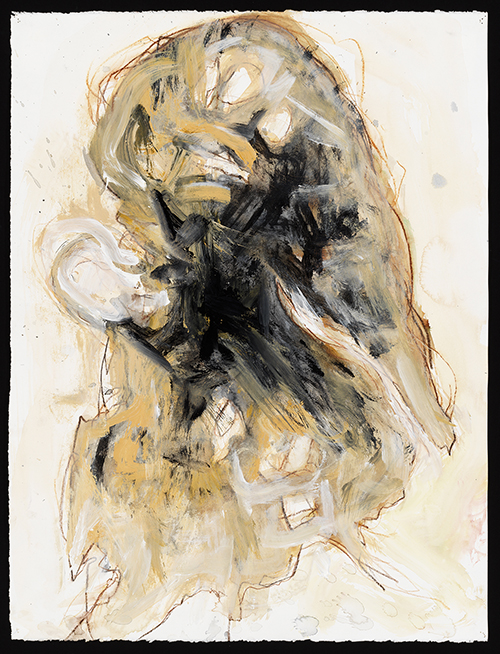

“Pillars of Dust” is constructed of paint and charcoal massaged on canvas and paper grounds. Painted forms pool like sludge in a dry creek bed or drift like dust across deer-paths. Willowy contours crowd the margins. Other pieces are scaled up to reveal cavernous interiors that appear to expose generations of land degradation. This is Paxton’s homage to one of the most beautiful, mineral rich places on the planet.

Michael’s fragmented “raw and cooked” images derive from his early life in Southern West Virginia but have commonalities between artists and critics who have extended biographical connections with place. Their observations about the ordinary and peripheral have long been framed as the other in the official art-world and in popular culture. Appalachian contemporary art is a threat to the larger monoculture which has no room for breadth and multiplicity of contemporary life. This dismisses the living art of any marginalized culture, however, whose mission is to shed light on the stylistic and conceptual models of place and identity.

For Paxton, the subject matter may be brittle but it’s also melodic. He applies the past to the present, the plain with the extraordinary, fact with mythology – resuscitating pattern, narrative and design from where they dissolve in memory. He has long seized on the value of everyday activities, labor and colloquial speech recurring like music, poetry or prayer. He embraces the grief of a historic ethnic migration, along with its nerve and world-weariness and just enough light to reconcile the veiled knowledge of a humbler birthright.

Drawing by Michael K. Paxton, “Beige and Black,” 30” x 22”

2018; chalk, ink, gesso, acrylic on paper (PHOTO BY TOM VAN EYNDE)