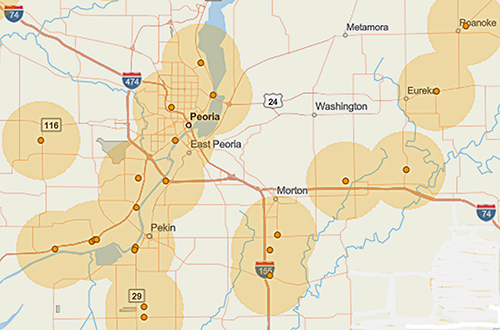

This map, referenced in the Fenceline report illustrates locations in central Illinois where toxic sites are close to people and schools.

Five years ago, a fire at a fertilizer plant in West, Texas, resulted in an explosion that created a 93-foot crater; destroyed more than 150 buildings, including an apartment building and school; killed 15 people; and injured 160 others.

In central Illinois, about 165,000 people live within a few miles of similarly risky places – more than 20 area chemical sites, according to a new study.

“Life at the Fenceline: Understanding Cumulative Health Hazards in Environmental Justice Communities,” from the Environmental Justice Health Alliance, Coming Clean and the Campaign for Healthier Solutions, notes that no accidents nor violations of existing regulations have been reported in central Illinois. However, even legal air pollution can be dangerous, and such incidents are possible, if not inevitable.

“Accidents at these facilities are fairly routine,” reported Eric Whalen in Earth Island Journal. “The EPA reports that, over the last five years, these chemical plants [nationally] have had over 1,200 accidents. Roughly 16,000 people were injured in these accidents, and 160,000 people were forced to evacuate.”

The report’s interactive map shows that 124 million Americans live within three miles of facilities that store or make large amounts of toxic gas or explosive materials, like large refineries, chemical manufacturers and even water-treatment facilities. That’s almost 40 percent of Americans living, working or playing under threat of chemical exposure, says the study, which adds that if an accident happens, people as far as 25 miles away could be affected.

In central Illinois, about 43 tons of toxic or dangerous substances and 258 tons of flammable chemicals are stored or manufactured at the 20 sites in this area, the report says.

“Peoria has environmental-justice issues such as air pollution from the Edwards coal-fired power plant and from Keystone and ADM, which prevailing winds carry to the south side of the city and minority and poverty-stricken neighborhoods,” said Joyce Blumenshine of the Sierra Club’s Heart of Illinois Group. “The historic, local grassroots effort to stop the expansion of PDC’s hazardous-waste landfill is a key example because the fenceline residents to that toxic waste site are low-income and predominantly minorities in the apartments off Reservoir Boulevard, many low-income, disabled and elderly in that neighborhood, and Pottstown and nearby mobile homes.”

Designated by the EPA as Risk Management Plan (RMP) facilities, the companies in the report must develop such plans in case of emergencies and update them every few years.

“Health impacts from the pollutants can mean major health problems such as asthma attacks and other lung conditions or simply headaches, fatigue, and less well-being because of poorer air quality,” Blumenshine added.

In the greater Peoria area, affected populations by zip codes range from 43,000 in Pekin, 31,000 in the Bellevue area and 28,000 on Peoria’s south side, to rural communities with 1,100 in both Deer Creek and Goodfield and about 300 in Kingston Mines. The median household income within the zip codes is $44,000, from the lowest on the south side to $72,000 in Mapleton.

Further, the Fenceline report says, “Compared to national averages, a significantly greater proportion of African Americans, Latinos and people at or near poverty levels tend to live in close proximity to the most hazardous facilities. Compounding these risks, a large and growing body of research has found that people of color and those living in poverty are exposed to higher levels of environmental pollution than Whites or people not living in poverty.”

Denise Moore, a City Council representative from the First District on Peoria’s south side (where the median household income is about $19,000), voiced concerns.

“It is not very often you see such companies locating in high-valued areas due to the cost of land and greater community oversight and resistance,” she said. “It becomes a matter of economics and ease-of-entry as to where these companies locate.

“The question really is who is looking out for the best interests of residents,” she continued. “Having said that, I believe that companies locate in areas adjacent to low-income residents because regulatory agencies may rely too heavily on companies’ reports of community feedback. In addition, companies [can] make an illegitimate case of bringing value to an unimproved, low-income area emphasizing the promise of jobs; that rarely materializes. If regulatory agencies believe there is no or little opposition, approval is often granted. Once constructed, actions to rein in health-threatening behavior are more difficult.”

The 60-page report’s findings note:

- Chemicals used within a few miles of central Illinois neighborhoods include ammonia and chlorine, with some companies using carcinogens, such as Archer-Daniels-Midland (hexane and acetaldehyde) and others using toxins such as Chemtura (ethyl chloride and hydrochloric acid), according to the EPA’s latest National Air Toxics Assessment.

- 45 percent of the approximately 125,000 schools in the United States are located within three miles of

RMP facilities. This puts more than 24 million children and their educators at risk. - 39 percent of almost 11,000 hospitals and nursing homes in the United States are near RMP facilities, and they could be difficult to evacuate in emergencies.

The U.S. EPA and Illinois EPA try to monitor such sites, but cutbacks have drained resources, and the Trump administration has sought to block improved safety measures for such hazardous chemical facilities. However, a lawsuit by the Sierra Club, the Union of Concerned Scientists and others forced Clean Air Act safety improvements to take effect.

“While these bolstered safety measures stand for the moment, Trump’s EPA, under Acting Administrator Andrew Wheeler, is now pursuing an effort to roll them back outright. It’s essential that the disaster-prevention measures remain intact to reduce risks in fenceline communities across the country,” Whalen wrote.

Illinois Attorney General Lisa Madigan’s office – which in September complained that the IEPA wouldn’t release emission reports from a Chicago-area plant – has described current safeguards as “alarmingly inadequate.”

As Blumenshine said, citizens’ actions sometimes work. For instance, the Illinois Pollution Control Board this fall shelved Gov. Bruce Rauner’s proposal to relax limits on pollution from some coal-fired power plants in Illinois. It affects the Edwards plant in Pekin previously operated by Dynegy and now owned by Vistra Energy. The PCB ruled that the cap be lowered to a level recommended by the Attorney General’s office, and it’s tentatively scheduled additional hearings on its decision Jan. 29 and 30 in Springfield.

“Residents can provide their representatives with power when residents organize, become familiar with the company’s organizational structure (where the ‘pain points’ may be), and understand and articulate the negative health concerns that are impacting their community,” said Moore. “In small cities, where elected representatives are part-time, have no staff and no budget, it can be a challenge to direct this type of resistance. It has been national organizations that often bring awareness and resources to assist residents in mounting a challenge to company apathy about health concerns. It can be done. However, it is not fast, cheap or easy.”

The study’s sources and recommendations

Organizations behind the comprehensive study are “Coming Clean,” a national environmental health and justice collaborative of 200 organizations working to reform the chemical and fossil-fuels industries so they are no longer a source of harm and to secure changes that allow a safe chemical and clean-energy economy to flourish [www.comingcleaninc.org]; and the Environmental Justice Health Alliance for Chemical Policy Reform, a network of grassroots environmental-justice organizations in communities disproportionately impacted by toxic chemicals.

Their report makes several recommendations, including:

- Government should strengthen the enforcement of existing environmental and workplace health and safety regulations. “Congress should increase funding to the EPA, OSHA and the states for expanding inspections and improving the enforcement of environmental and workplace health and safety laws so that problems in chemical facilities can be identified before they lead to disasters.”

- Government should require publicly accessible, formal health-impact assessments and mitigation plans to gauge the cumulative impact of hazardous chemical exposures on fenceline communities. “Federal, state and local agencies should assess, with full participation by affected communities, the potential impact of unplanned chemical releases and the cumulative impacts of daily air-pollution exposures on the health of fenceline communities.”

- Government should mandate large chemical facilities to continuously monitor, report and reduce their fenceline-area emissions and health hazards. “Unplanned, smaller releases of toxic chemicals often precede more serious incidents at chemical facilities and may directly impact the health of people. Continuous, publicly available monitoring of air emissions will improve community knowledge of hazards and potentially help prevent minor issues from leading to major disasters.”

- Government should prevent the construction of new or expanded chemical facilities near homes and schools, and the siting of new homes and schools near facilities that use or store hazardous chemicals. “The siting of new facilities that use or store hazardous chemicals, or expansion of existing ones, near homes, schools or playgrounds increases the possibility that a chemical release or explosion will result in a disaster. Similarly, new homes, schools and playgrounds should not be sited near hazardous facilities.”

- Facilities themselves must share information on hazards and solutions, and emergency-response plans, with fenceline communities and workers. “Employees and neighbors can only participate effectively in their own protection if they have full access to information and to decision-making processes. First responders must know what hazards they face.”

- Facilities that use or store hazardous chemicals must adopt safer chemicals and processes. “Switching to inherently safer chemicals and technologies – which removes underlying hazards – is the most effective way to prevent deaths and injuries from chemical disasters (as well as eliminate ongoing emissions of the replaced chemicals).”

While these may seem sensible, some may wonder whether they’re feasible – especially concerning government reform.

“The recommendations should be followed,” said State Rep. Jehan Gordon-Booth, D-Peoria. “They were recommended for a reason and that reason is the safety of our fellow citizens. The feasibility of these recommendations has everything to do with whether or not there is a political will to follow through. These recommendations will be expensive, so it will be competing with all of the other spaces that compete for a place at the local, state and federal appropriations table. It will be incredibly important for community members to continue to make their voices heard on this issue to ensure that their elected representatives know that this is an issue that they deeply care about.”

State Sen. Dave Koehler, D-Peoria, chair of the Senate’s Environmental and Conservation Committee added that they might be achievable.

“I would welcome a hearing on environmental-justice issues,” Koehler said. “Under a new Pritzker administration, the new EPA director will hopefully tune in to this.”

1 comment for “Toxins in our neighborhood”