BILL KNIGHT

Given the general characteristics of status-quo Peoria and youths’ attraction to exciting punk music on both coasts, those forces were destined to Clash. (So to speak.)

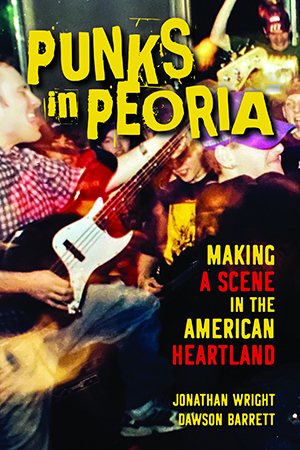

Out in June, “Punks in Peoria: Making A Scene in The American Heartland” from the University of Illinois Press shows how, looking at punk’s birth and growth here. It’s as exhilarating as a boarding down Mt. Doom.

The backdrop in the 1970s and ‘80s was an economic downturn reflected in factories closing, workers striking Caterpillar and social chaos. Like “greasers, hippies and garage rockers,” the book says, “punk rock offered a sense of belonging, a community in opposition to ‘the system’.”

Peoria’s punk scene was “an ever-changing ebb and flow of bands, friends, supporters and hangers-on – constantly turning over, and those who made up the scene were generally unaware of what came before.”

Co-written by Jonathan Wright (Peoria Magazines editor) and Dawson Barrett (author of “The Defiant: Protest Movements in Post-Liberal America”), it documents some of what came before: area musicians featured in Peoria such as Wild Child Gipson, Freddie Tieken & the Rockers, and Luther Allison, performances by James Brown, the Yardbirds, and Tina Turner, plus the Who headlining a concert opened by local bands the Coachmen (with Dan Fogelberg) and Suburban 9 to 5 (with future REO guitarist Gary Richrath). Later, the MC5 and the Runaways energized interest in high-energy rock.

Co-written by Jonathan Wright (Peoria Magazines editor) and Dawson Barrett (author of “The Defiant: Protest Movements in Post-Liberal America”), it documents some of what came before: area musicians featured in Peoria such as Wild Child Gipson, Freddie Tieken & the Rockers, and Luther Allison, performances by James Brown, the Yardbirds, and Tina Turner, plus the Who headlining a concert opened by local bands the Coachmen (with Dan Fogelberg) and Suburban 9 to 5 (with future REO guitarist Gary Richrath). Later, the MC5 and the Runaways energized interest in high-energy rock.

Throughout, the illustrated book is a well-reported account of the local rise of and changes in punk music, blending overlapping histories with Barrett and Wright’s cultural commentary. They concede Peoria probably wasn’t unique, but one example of a fever breaking from the Bible Belt/Rust Belt, a timeless search for friends and fun. In fact, the search extended to Bloomington/Normal and Champaign/Urbana to the east and west to Bushnell, where the Cornerstone Music Festival for about 20 years gathered 20,000 spectators for Christian rock, metal, folk and punk groups.

Although generalized as two camps – “sex-drugs-rock ‘n’ roll” types and “straight-edge” skateboarders – people gathered together at various places for Do It Yourself/underground shows for peers listening to hardcore, indie rock, synth, thrash metal …

“It was goth kids, gay kids, punk-rock kids, nerds and dorks … music people,” remembered musician Matt Shane. ‘Totally open; really cool.”

“Peoria’s introduction to punk” may have been in 1974, when David Bowie released “Rebel Rebel” and Peoria’s Jets covered the single hours later, says Jets guitarist Graham Walker. Memories differ, but most hare recollections of places where people gathered and music(s) happened: Expo Gardens, veterans halls, Owens Center, ICC, Co-op Tapes & Records, Fulton Plaza, Airwaves Skate Park, Morton’s Optimist Club, Tiamat Records, Pizza Works and assorted church basements and barns, where onstage outrage often spilled outside or into crowds, with mayhem devolving into fights and police, like a notorious near-riot at the German-American Hall.

Wright and Barrett remember many individuals too: promoters from Hank Skinner and Jay Goldberg to James Eric Williamson and Wright himself; musicians like Planes Mistaken for Stars and Scott Ligon of Geek Love, Dollface and the River City Soul Revue, and eventually the legendary, eclectic recording artists NRBQ; punk fanzine publisher and Prairie SUN writer Jon Ginoli, founder of San Francisco’s Pansy Division band.

Mostly affectionate, the text is sometimes unsparing in its observations. Bloody F. Mess is “a strong personality” (an understated description of the confrontational character who was more of a performance artist than a talented musician). Bloody takes credit for helping “create the first punk rock scene in Peoria in the early ‘80s,” and now lives in Oregon, where he says he’s adopted Hindu ways.

Beyond name-dropping, the 231-page paperback provides revealing context and appreciation. Peoria punks defied stereotypes, adopting the once-derogatory term “corn chips” as a sign they were fine with being “different,” and sometimes standing up as Skinheads Against Racial Prejudice (SHARP) and protesting white supremacists such as Matt Hale.

Ultimately, DIY or semi-pro organizers brought in bigger, better acts, from Naked Raygun to Fugazi, achieving a sense of recognition, if not mainstream “legitimacy.”

Saying the project was “heartwarming and heartbreaking,” the authors add, “This book has given us the opportunity to visit the past, but we are glad not to be living in it.” In a nod to the Vaudeville-era phrase about Peoria being a tough proving ground for entertainment, the pair continues, “What played in Peoria, in many cases, really could play anywhere.”

Kate Dusenbery, a local musician who in the ‘90s played with Walpurgis Nacht, said, “The main thing that Peoria instilled in me is the ability to make something from nothing.” A related “soundtrack” featuring music from Caustic Defiance, Chips Patrol and 12 other acts is available with pre-orders. For details, go to www.punksinpeoria.com.

3 comments for “Bill Knight | “Punks in Peoria””