WILLIAM RAU

Several themes guide this series. First, climate deterioration demands rapid abolition of fossil-fuel emissions. Trees cannot substitute for ending emissions. However, we must also extract LOTS of atmospheric carbon. Half of above-ground tree mass consists of carbon absorbed through photosynthesis. So, expansion and long-term preservation of trees trump other means for sequestering carbon. Next, let woodlands and forests regenerate naturally. Some massively degraded areas will need assistance, but broadcasting seeds from forest remnants may do the work better and cheaper than foolish mortals’ planted saplings.

Suburban backyards can showcase natural regeneration. After berming the bottom of my yard’s hill, I routed gutter water into a swale planted with wildflowers and prairie grasses. Midwest Permaculture taught me to plant trees behind berms (Fig. 1), but berms can also become natural nurseries where bird- and wind-tossed tree seeds flourish. Unattended, my berm grew its own +10-foot hackberry, several Illinois pecans and several redbuds. Two redbuds were moved to moist spots elsewhere and a honey locust was placed ‘upswale.’ Lots of free trees!

Desperation forced Niger farmers in dryland Africa to choose assisted tree regeneration. Population growth and dependency on wood for cooking fuel led to rapid deforestation. Without trees, 35 to 45 mile winds sandblasted crops. Sun dried out the soil turning it into hardpan. Skimpy yields and drought brought chronic hunger. Government ownership of trees strengthened famers’ beliefs that tree sprouts were weeds to be cleared and doomed efforts to protect them.

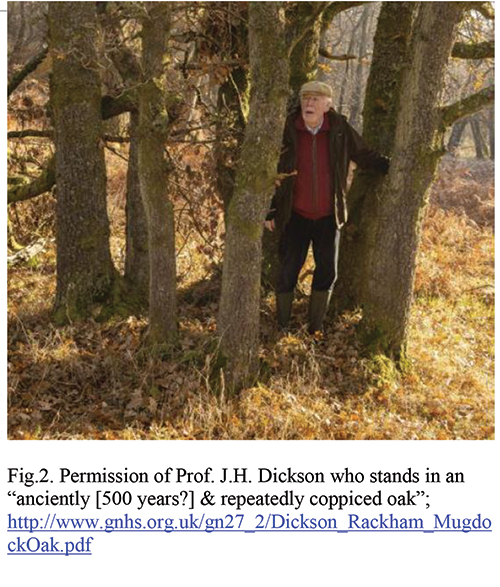

Tony Rinaudo, working with Serving in Mission, helped break the downward spiral. Finding farmers’ fields riddled with living tree stumps – an “underground forest” – he taught them to coppice and pollard trunks. Pruning shoots growing from the trunks for wood (coppicing) or for fruit or animal fodder (pollarding), keeps trees in a juvenile stage thus extending their lives many fold. Rotating areas pruned increases bio-diversity by varying the light and thus the range of plants growing under trees.

After Rinaudo’s demonstrations, and elimination of government tree ownership, innovating farmers began regenerating trees. Others improved indigenous versions of (stone) berms and swales (zaï). The innovations proved successful and spread from farmer to farmer until hundreds of thousands became involved and were soon re-sprouting over 1 million trees per year. Largely on their own, farmers regreened 12 million degraded acres in Niger’s Sahel.

Benefits were many, some immediate. Women harvested coppice firewood near their homes rather than spending hours scouring the countryside. Animal dung, previously used for fires, was now spread in swales (zaï). Trees reduced wind damage, lowered temperatures, raised humidity, improved animal health (shade and leaf fodder), increased soil fertility by adding organic residues to animal dung, and provided additional ‘fertilizer’ when nitrogen-fixing trees were regenerated. Stone berms, zaï, and trees captured rainwater for crops while recharging water wells. The latter allowed some well-adjacent vegetable gardening. Birds and wild animals also returned. Crop yields, farmer income and security (tree products) increased. The biggest gains, however, were communal. Confusion and despair, a dying environment’s handmaidens, were replaced, through collective mobilization, by farmers’ growing hope that they had regained control over their own lives, lands, and livelihoods.

Next, we turn to spontaneous forest regeneration and then on to urban tree inequality.

References

Reij, Chris, et al. 2009. Agroenvironmental transformation in the Sahel: Another kind of “Green Revolution”. International Food Policy Research Institute; https://www.researchgate.net/publication/239807425_Agroenvironmental_transformation_in_the_Sahel_Another_kind_of_Green_Revolution

Rinuado, Tony. 2001. Utilizing the Underground Forest. Springer; https://www.researchgate.net/publication/302237465_Utilizing_the_Underground_Forest

Rockham, Oliver. 2002. Ancient Forestry Practices. UNESCO-EOLSS; https://www.eolss.net/Sample-Chapters/C10/E5-01A-02-01.pdf

Weston, Peter et al. 2016. Farmer-Managed Natural Regeneration Enhances Rural Livelihoods in Dryland West Africa. Springer; https://www.researchgate.net/publication/301255005_Releasing_the_Underground_Forest

Wilson, Bill & Becky. 2021. Midwest Permaculture. Stelle, IL; https://midwestpermaculture.com/; https://midwestpermaculture.com/2012/07/hugelkultured-swale-with-linear-food-forest/

Wrench, Briana. 2012 (Nov 1). Coppicing/Pollarding. Midwest Permaculture; https://midwestpermaculture.com/2012/11/coppicingpollarding/