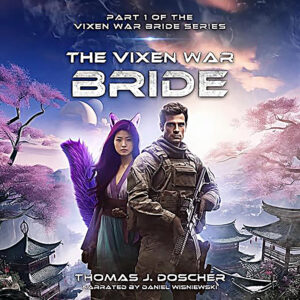

Army Ranger Captain Ben Gibson is in charge of Forward Operating Base Leonard outside the farming community Pelle.

Though Gibson has been tasked with “winning the peace,” the terrified residents of Pelle abandon the town, and the occupiers struggle with only a rudimentary understanding of Va’Shen language and culture.

A local priestess, Alacea, hopes that sacrificing herself might spare her people from the cruelty and death anticipated from the humans, whom they call the “Dark Ones.”

As misunderstandings multiply, the priestess and captain both lead their followers in a good-faith effort to find understanding and peace where mistrust threatens to reignite the war.

JS: How did you come up with this idea?

TD: So more than 15 years ago I was studying the [WWII] Pacific War, and I came upon an anecdote about an officer during the occupation of Japan. I don’t remember where I read about it, and I’ve looked for it since but couldn’t find it. But it always stuck with me.

This Army officer was in charge of an area where kamikaze pilots were trained and from where they deployed on their final missions. And shortly after (his) arriving, this woman marches into his office with the mayor right on her heels, basically begging her to shut up. She tells the officer that she’s there to turn herself in because she heard the Army was looking for possible war criminals.

It turned out that she ran the local inn where kamikaze pilots, who were mostly young men fresh out of flight school — practically kids — would spend their last night before their final missions. She and her staff would serve them a meal, drink with them, sing songs and pray with them. Then the pilots would leave, and they’d never see them again. That was her involvement in the quote “kamikaze program.” Well, obviously the Army was not looking for her and did not consider what she did as a crime, but the officer felt that telling her to just leave would be insulting, so he had her locked up in the town jail for a few hours and then let her go.

She walked out with her head high, and they never had any issues with her again. I always wondered if they had any interactions after that, and it just seemed like such a good setup for a story.

JS: So does that explain the Asian cultural themes and references?

TD: Yes. So my focus on my history studies is the Pacific War. I spent a year in Korea with the Air Force. The more I studied about the war, it just seemed to me that it was a clash of cultures, and it wasn’t just a war between military powers.

If you look at how the war in Europe and how the war in the Pacific were fought, they’re very different, and a lot of it has to do with the way the two cultures interacted.

Today, if you want to learn about Japanese culture or you want to watch a Japanese movie or a Korean movie, you could just go to Netflix, and you can get whatever you want.

Back then, however, unless you were well-traveled, you may never come across someone from Korea or Japan, and these farm boys coming into the military to fight, for all intents and purposes, they may as well have been fighting people from the moon.

I guess in answer to your question, yeah, I used the Asian aesthetic, I think, as part of the background for the culture mostly because of where the original idea came from.

JS: How did you come up with the description of the Va’Shen?

TD: I’m a nerd. I like anime. The kitsune fox girl is a popular anime archetype. For the Va’Shen, I needed something close enough to human to make interpersonal relationships possible while still making them alien. So I couldn’t just make Alacea like a Vulcan from “Star Trek” with long ears. No one would care.

But with a kitsune, you end up with two camps: People who see them as like humans but a little different, and people who see them as animals who talk. I cannot tell you the number of people who have accused me of being a furry. But there are also a lot of people who think it’s not an issue. And that’s exactly the kind of divide I was going for, and it’s the kind of divide that exists in \ the story.

JS: How does your military background contribute to your work?

TD: I served 20 years in the U.S. Air Force as a public affairs writer so I had the military version of your job. I deployed four times, three of which were alongside Army units where I learned a little bit of what their life was like.

I guess one thing I should probably point out is that on one hand, yes, the Va’Shen culture is something I had to be careful of, but I also wanted to be very careful of the Army culture because it is very different from what the Air Force culture is. So I have to be very careful about that as well. There are parts of the books that are inspired by actual events that happened to me and to a lot of the people I served with and talked to. So my military background has contributed a lot to these books.

One of the things I really wanted to do was give readers a feel for what the military is like on the inside. So much of what people see in popular media about the military is colored by two opposing cultural narratives.

Either the military is filled with nothing but brave heroes, paragons of virtue who are wise and gentle and just, or it is filled by slack-jawed morons who are trapped there because they’re not smart enough to do anything else or they just like hurting people.

This happens because of a couple of reasons. On one side, the military will offer a movie producer assistance and vehicles and advisors but in exchange they get a say in how the military is presented in the final product. The military will not help someone crap on itself.

On the other, a producer may not want to be subject to those restrictions but doesn’t know anything about the military other than what their non-military friends have told them and movies they’ve seen like “Full Metal Jacket.” This is why you often see people in the military in movies and TV shows yelling “Sir, yes sir!” during a regular conversation or you have formations of troops running down the road every 10 minutes singing cadence.

The truth encompasses both extremes but mostly in the middle. Most people in the military are professionals doing their jobs as best they can. Some are great people and some are the absolute worst humanity has to offer. But most are just folk getting through the day. Just like everywhere else.

JS: What informed the intercultural difficulties and understanding in the books?

TD: So some of it’s from studies, and some of it’s from personal experience. So little things can have large impacts on the relationship between two people. Things one considers normal or right can seem the exact opposite to someone else, where you walk in relation to someone else, which way your hand waves, whether the bottom of your feet are showing. For some, it’s nothing, and for some, it’s everything, and that’s just between humans. You know, I can’t imagine what it’s going to be like when we actually do make contact with aliens some day.

I think Americans, maybe because we’re such a relaxed or liberal or casual culture, sometimes it’s harder for us to understand more traditional or restrictive cultures, right?

JS: Most of your main characters are trying to understand each other.

TD: That was the thing I wanted all my characters (to do), but they’re all trying to do the right thing. And even some of the villains, you know, are — in their mind — doing the right thing.

Major Keyes, just for example, you know, we look at that guy, and he’s an obvious villain, he’s a monster. But, you know, you look at things from his perspective, and he is doing the things he thinks are right.

So it’s always a little more complicated than right or wrong, yes or no, good or bad. Communication is hard.