In Museums, one of the most significant roles is the curator — whose responsibilities are to create a specific collection of objects with a varied list of goals. This closely identified group becomes the exhibition. It is here where education, appreciation for content, for meaning, and — hopefully — for public discussion, originate.

Currently at the Peoria Riverfront Museum there is a curious caveat — an exhibition-within-an-exhibition. “Solitude: The Necessity of Art” is a contemplative assemblage of masterworks from the distant past to the ever present. Within its confines is a reference collection of renown Illinois artist Nicolas Africano. This very local artist from Normal is recognized as one of the most prominent Imagists, an important art movement of the 1980s and 1990s. His rise to prominence was based on his figurative works that existed in solitude unlike any of his peers in the art world at that time.

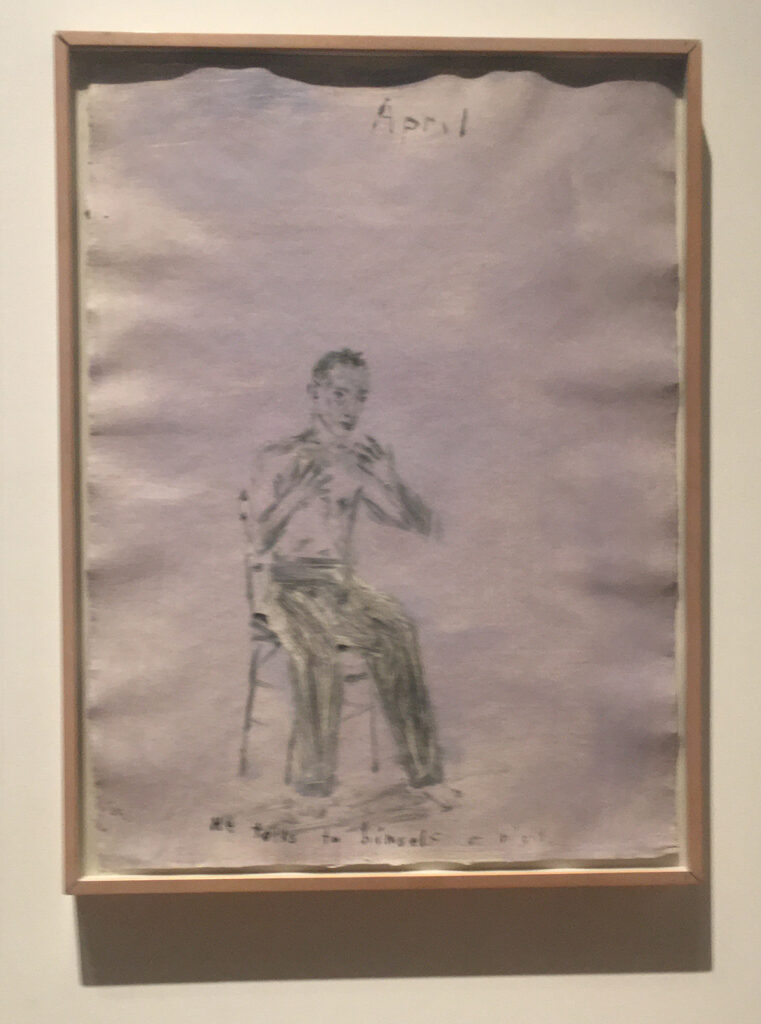

Africano is a master of materiality. Watercolor, ink or oil, all of these mediums are fluid in his hands. The brush to paper or canvas results in characters that represent mankind in typically a calm manner. Whether standing, lying or kneeling, an Africano figure commands our attention in the quietest way. Unlike a de Kooning’s thrashing of strokes which often decimates the soul, Africano takes hold of our hands and eyes, and gently guides us.

So often, interwoven into a work are words or music, any of these seemingly random scrawls insist that the viewer speak of them out loud. The melody of a floating snippet of notes or the juxtaposition of sometimes awkward gestures and/or words provide us with an introduction to his psyche.

This element of natural poetry breaks the solemn moment with contemplation of innocence or wretchedness. Angst comes into play when we realize that this insignificant pause has totally engulfed our presence before his painting. One example is “An occasion for hope” which ignites the hope in all of us. Be it as such, it demonstrates how the artist can engage our spirits with those of strangers.

“He talks to himself at night” suggests a simple human characteristic that we all indulge in — working out our own restlessness left to our own devices when we need it the most. This lone figure can be any one of us.

At times, Africano presents unanswered questions. In this exhibition, consider this temporary encounter of queries, an opportunity to appreciate the genius of the artist and seek your own answers.

The recent purchase “Daddy’s Old (Rich Lady)”— a purse which contains seven small sketches documenting random acts on any given day and a letter addressed to Holly Solomon, a gallerist in New York City. Simple, direct images of normal people constrained to a minimal space are pure Africano. His ability to remove all emotional, evocative elements from the picture plane only reinforces his independence of emotional and sentimental factors. As intruders, viewers are captivated for a moment in a life that is not their own.

Africano’s gestures and understanding of materials transcends function to become a carrier of history, space, and cultural resonance. These are a means of expressing the complexity of our own memories. His physical touch is charged with the weight of hands connecting past to present, tradition to contemporary expression.

Africano has developed the figure (which dominates his present work) through various materials which, in turn, have evolved into natural physical adaptations of his figures. The constant through decades of work is the desire to reveal personal narratives focusing on the complexities of human interaction.

Bill Conger, Chief Curator at the Peoria Riverfront Museum, explains, “Currently in the gallery are two recent museum purchases of glass busts that truly command the gallery space. With her tilted head and heavy-lidded eyes, Africano’s “Teresa,” which loosely echoes Bernini’s “Ecstacy of St. Teresa” (1652), features two scars which arrived to the piece from a flaw in the cast glass. Through this imperfection, he inevitably saw the opportunity to symbolically render wounds of the flesh. Her counterpart “Bell,” is adorned with a bell tied around her neck as Africano’s young father did when he first arrived on the foreign-speaking shores of America in assurance that he would not wander.”

Conger continues, “Devoting a large amount of his studio practice to the ineffable medium of glass for the past 25 years, Nicolas Africano’s subject matter has primarily focused on his wife Rebecca, for whom Nicolas has suspended in reverie for the near-entirety of his mature work. Africano has repeatedly sculpted, painted and drawn Rebecca singularly and as twins. The entrancing qualities of Africano’s glass work allow for individual interpretations about his figures, however they are steeped in confessional sentiment, which is rooted in both intimacy and distance.”

This exhibition is made possible through the support and generosity of Alice Walton and the Art Bridges Foundation, through a grant from the Illinois Arts Council, from Thomas Solomon Art Advisory, Inc., Andrew Muir’s collection, the Visionary Society and the Peoria Riverfront Museum’s collection.

The Peoria Riverfront Museum is located at 222 SW Washington St. in Peoria. Museum hours are 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Tuesday-Saturday and 12-5 p.m. Sunday.