Just as health-care costs remain a dilemma despite better insurance coverage, college costs aren’t being addressed much in discussions of education in general and student loans in particular.

Students’ loans and the enormous debt they create are a problem, but they’re tied to costs that too much of higher education is ignoring, almost like science deniers burying heads in sand at facts about climate change.

Locally, there’s concern about enrollment at Bradley University, which reports a 4.4 percent drop in freshmen since 2010, and a 4.7 percent decline in overall undergraduate enrollment over the same period.

Faculty members face more belt-tightening, but few administrators talk about rising tuition costs (see box), much less consider pay cuts, furloughs or layoffs at the top.

For example, Bradley reports having raised tuition and fees from $25,150 in 2010 to $29,320 last year – a 16.7 percent increase.

Of course, such price hikes add to many graduates’ debt, at best; at worst, it limits access to higher education, adversely affects enrollments, and hurts the U.S. economy.

It’s a vicious cycle in both private and public institutions: Enrollments are falling; legislatures are cutting funds to public-supported schools; and families are further held back or financially burdened.

And college employees are increasingly expected to shoulder an escalating amount of that load.

On campuses, too many college teachers are now badly paid part-timers working without benefits – 30 percent of today’s college professors are on “tenure-track” (meaning with decent pay and benefits, with job security), compared to about twice that number 40 years ago.

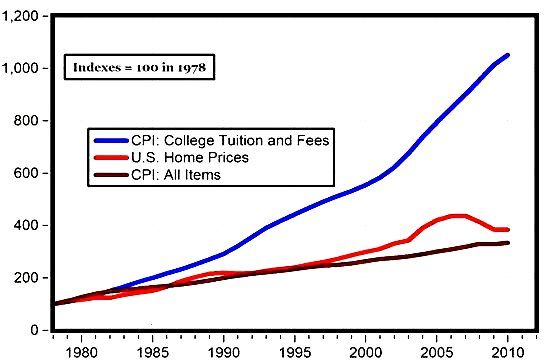

Thomas Frank – author of “One Market Under God,” “Pity the Billionaire” and “What’s The Matter with Kansas?” – reported that U.S. college costs are up more than 1,000 percent since the 1980s – twice the exorbitant inflation of health-care costs.

About 40 million American borrowers owe more than $1.2 trillion from going to college; the average is $27,000; new graduates are trying to join the labor force with an average of $33,000 in loans, according to the Wall Street Journal; and government efforts to help have had mixed results.

The college loan debt is the largest ever for the Class of 2014 – not only much higher than previous generations, but much less than students in France, Germany, even Argentina and Mexico.

As part of President Obama’s “Fair Shot for Everyone” agenda he recently announced new loan forgiveness terms. First, he ordered the Education Department to make lower annual student-loan repayments available to students and graduates who borrowed money before October 2007, not just after that, plus renegotiate with companies that service federal student loans.

His Executive Order targets 5 million Americans not able to take part in the federal Pay as You Earn program, which had capped monthly payments at 10 percent of borrowers’ income.

American Federation of Teachers President Randi Weingarten endorsed both the Executive Order and a bill introduced by U.S. Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.).

“No student should have to face the triple threat of skyrocketing higher education cost, high interest rates and crushing student loan payments,” Weingarten said. “We must reclaim the promise of higher education by making college affordable and accessible to all Americans.”

Senate Republicans disagreed, as the GOP (except for three: Maine’s Susan Collins, Tennessee’s Bob Corker and Alaska’s Lisa Murkowski) last month blocked the Bank on Students Emergency Loan Refinancing Act (S. 2432).

Warren’s measure would have let students refinance loans with interest rates of up to 7 percent to rates as low as 3.68 percent. It would not have erased the debt, but made loans more manageable, as consumers often do in refinancing.

The act would have paid for itself by implementing the “Buffett Rule,” which closes tax loopholes for people who make more than $1 million a year.

The vote was 56-38, but 60 votes were needed to break a filibuster and debate it.

This would have let the nearly 40 million Americans – including thousands of borrowers in their 60s who still collectively owe $43 billion, Warren said – save hundreds to thousands of dollars a year and in turn stimulate the economy.

After all, that debt hurts the economy because people weighed down with such debt starting out cannot buy durable goods, cars and homes.

Obama asked how anyone can justify letting “tax loopholes for the very, very fortunate survive while students are having trouble just getting started in their lives.”

Meanwhile, two recent reports are critical of higher education’s management and the notion that colleges should follow a business model based on corporate goals rather than academic or social ends.

The non-profit think tank Demos’ 2013 report “The Great Cost Shift: How Higher Education Cuts Undermine the Future Middle Class” shows how state disinvestment in public higher education over the past two decades has shifted costs to students and their families.

“As a result, students and their families now pay – or borrow – a lot more for a college degree or are getting priced out of an education that has become a requirement for getting a decent job and entering the middle class,” it states.

Elsewhere, the Institute for Policy Studies’ 2014 study “The One Percent at State U: How Public University Presidents Profit from Rising Student Debt and Low-Wage Faculty Labor” contrasts rising executive pay and falling support for faculty.

Also focusing on public universities, the report examines the correlation between top administrators’ salaries with rising student debt and an increased dependence on low-wage, part-time faculty workers. In public and private high ed alike, administrative positions are up, too – the number of these “dealings” has more than tripled since 1976, Frank said.

“In the public debate, these issues are often treated separately,” the report says. “Our findings suggest these issues are closely related and should be addressed together.”

Over the last few decades, there’s been a trend to operate colleges according to a management approach that’s more business-oriented (a model that’s arguably resulted in a national economy enriching elite and causing everyone else to struggle). For instance, rising administrator pay is justified as being “at market and very competitive,” echoing the rationale for excessive CEO pay in the corporate world.

It’s not always been a progressive-conservative debate either. Conservative Republican commentator and former Education Secretary William Bennett years ago said, “Colleges raise costs because they can.”

Frank, a progressive, considered why colleges for decades have continued to raise prices and saddled students with huge debts and said, “The answer is obvious. It happened because these things are all related: Deregulation, tax cuts, de-unionization and outrageous tuition inflation are all part of the same historical turn.”

Colleges’ excuses for rising tuition have ranged from higher utility costs, new buildings and libraries to amenities needed to better attract students, government regulations such as Title IX and Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) requirements and, of course, those dad-blamed faculty.

Some college administrators even blame creeping tuition hikes on falling enrollment, a counterintuitive, if not short-sighted or even false, assertion that seems to blame the victims.

Others trot out the old canard that higher prices (and the debts that pay for them) ultimately will be justified by realizing the promise of future financial returns, an oversimplification of prospects. Such returns on that substantial investment, effort and time aren’t guaranteed.

In fact, a recent Federal Reserve Bank of New York study tried to add perspective, reality even, to that claim.

“The relatively high unemployment experienced by recent college graduates should not prompt us to dismiss the value of a college education,” wrote co-authors Jaison R. Abel, Richard Deitz and Yaqin Su. “However, with the onset of the Great Recession and the sluggish labor market recovery that has ensued, there have been widespread reports of newly minted college graduates who are unsuccessful at finding jobs suited to their level of education.

With unemployment for 20- to 24-year-old college grads so high – 10.6 percent – it’s not unreasonable for students and their families to question the value of a degree and the whether it’s worth going in to such much debt to earn one.

“It has become more difficult over the past decade for recent college graduates to find jobs that utilize their degrees,” the Fed report notes.

Frank is more dismissive, saying, “College costs more and more even as it gets objectively worse and worse.”

Maybe today’s educators should stop thinking of college strictly in commercial terms and try to revive the idea that education is a social investment that helps create and maintain a public good for communities.

Recent Comments