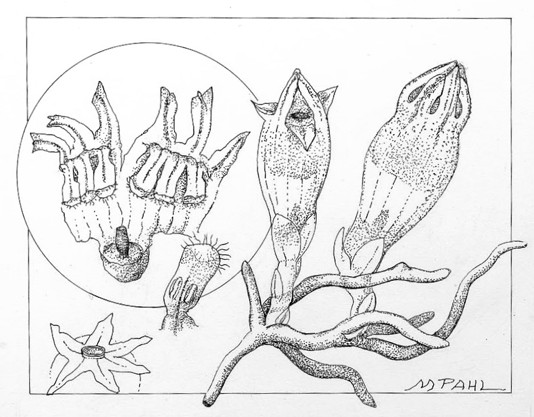

On a summer collecting trip in Northern Illinois, a botanist made “a most remarkable find” near Lake Calumet in Cook County. No, it wasn’t gold or platinum . . . . It was something far more rare. A diminutive flower of the Sand Prairie – unique in all of the world – known only as Thismia americana.

That was 1912. A one of a kind plant in a one of a kind place. There are eight known species of Thismia in the world. Thismia americana is the only one known to grow in the north temperate zone. All others grow in Indo-Malaya and south to Tasmania. A tiny flower precariously perched upon the sandy shores of Chicago, growing nowhere else on the planet. The last year it was seen was 1916.

The problem with being such a rarity is that it is very easy to become extinct. Such was the fate of Thismia americana. The wet, sand prairie soon became the intersection of 119th Street and Torrence Avenue, a growing industrial neighborhood in South Deering. The shores of Lake Calumet have been transformed into a succession of industrial redevelopment and decay. The home of this long extinct plant is now a cluster of sites designated by the EPA as “The Lake Calumet Cluster,” a Superfund Site where excavation workers must wear self-contained breathing apparatus just to dig a hole . . . . A real testament to ability to create hell on earth.

Extinction effects mankind in a couple of ways. First and foremost is the ethical nature of the problem. We often rationalize modern extinction by believing that the human race does not maliciously strike out at nature with the sole intent of causing extinctions. Extinction then becomes a byproduct of our efforts to expand industrialization and spur economic growth. However, be it malicious or merely an after effect, the bottom line is the same. Something precious is gone forever. How long will we be content with pleading ignorance? How many ghosts will it take to keep us up at night? If history is a guidepost, there will be many more living things gone before we even start to think about the ramifications of our actions.

Western culture has a hard time feeling the sting of an ethical debate. While some in our society are disturbed by the prospects of extinction, collectively, as a society, our hide is much too thick. But extinction goes beyond the intrinsic or ethical view. It can effect our daily lives in a much more perceptible way. Ways our current knowledge base cannot even fathom. Take a look at the tropics for instance.

Plants and animals are becoming extinct there faster than people can discover them. In Hawaii alone 12.3 percent of the known native vegetation is now extinct, another 29.4 percent is endangered and 8.9 percent is threatened.

This is a scary thought when you realize that when you buy a drug or any other pharmaceutical, there is almost a 50:50 chance that we can thank the genetic resources of a wild species for the medicinal qualities. The value of medicinal products derived from wild plants and animals now approaches $40 billion every year.

You might remember that if you had leukemia as a child in the early 1960s you had a 1 in 5 chance of long-term survival. Now, thanks to two drugs developed from the Rosy Periwinkle, a tropical plant, you now have a 4 in 5 chance.

They say that about 10,000 plants and animals become extinct each year. We do know that in the early 1900s Thismia americana was one of them. Extinction is forever. There is no turning back.

We can only ponder if this plant was one of those living things that in some way could have helped fight the ever-growing onslaught of disease and suffering that plague our society. A tiny plant in the sand has become another ghost to weigh on our conscience. Unfortunately, it is not the last. Ten thousand species will join it this year. Soon the ghosts will outnumber the living.

Recent Comments