TV news audiences understandably could conclude mayhem rules, but that’s a flawed impression.

Broadcasters can decide “if it bleeds, it leads” newscasts because people care, or it’s usually cheap and easy (officials comment; there aren’t “pro-crime” lobbyists or advertisers to offend), or because it’s NEWS.

Faster/better reporting can mislead when crime is covered, perhaps because journalism’s default setting is optimism. Trains are expected to arrive safely, officials are expected to honestly represent constituents, and the public is expected to be safe. So when Amtrak derails, politicians are corrupt or crimes occur, that’s unexpected: That’s news.

But transportation tragedies, lousy politicians and crime aren’t common.

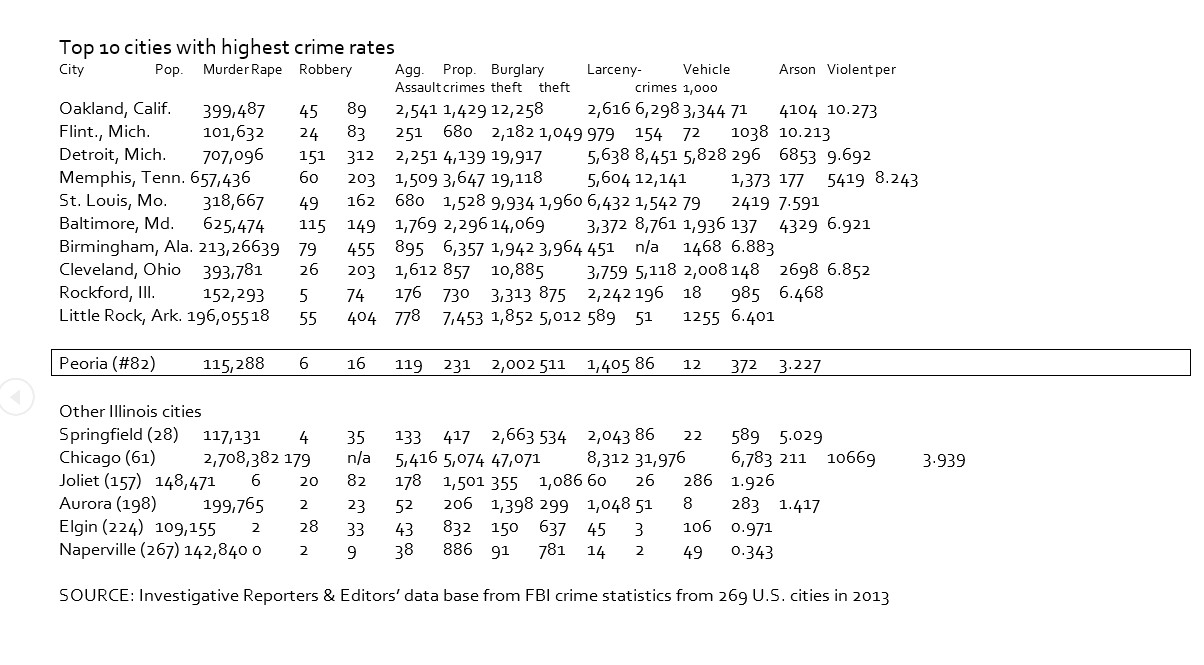

Peoria’s crime rates aren’t bad compared to the nation’s Top 10 or even Illinois cities. But public safety could be better, according to the County’s top prosecutor.

“We’re not ‘satisfied,’” said Peoria State’s Attorney Jerry Brady. “But I’m cautiously optimistic.”

In the most recent data, Peoria numbers for aggravated assault, robbery and murder are down from last year 4 percent, 17 percent and 56 percent, respectively. And details from FBI Uniform Crime Reporting records seem to be informative. But they’re also confusing. Detroit and Memphis have similar property-crime rates, but Memphis’ murder rate is less than half of Detroit’s. Rockford and Flint, Mich., are relatively small cities, but both are in the nation’s 10 worst cities for crime.

Further, New Yorkers are statistically safer than Peorians, with 2.929 crimes per 1,000 compared to Peoria’s 3.227 crimes per 1,000.

“To some extent, crime stats are critical to figuring out what’s going on,” Brady says. “It can measure our successes, like the Don’t Shoot program. It can be a good tool, but it doesn’t show a lot, too.”

Agencies voluntarily provide crime numbers to the FBI; they’re collected differently; and none show crimes unreported by victims or crimes prevented by police presence – or absence.

“There’s a police strategy called ‘hot spots,’ where high-crime neighborhoods get more attention, either because of one incident or an ongoing perceived need for a police presence,” Brady says. “However, hot zones might have three times as many law-abiding citizens as criminals, so they can start to resent police presence as an occupying force.”

Comparing a few Illinois cities, it’s difficult to see a pattern. Median ages (the midpoint of the range of ages) are comparable in Peoria, Rockford, Springfield and Chicago (between 33 and 38), but crime rates are vastly different, with Rockford’s almost twice as bad as Chicago’s. Household incomes correlate somewhat: Rockford’s median income is $48,000, Peoria’s $52,000, Springfield’s $55,000, and Chicago’s $60,000, following a descending crime-rate pattern. However, incomes don’t reflect costs of living.

Likewise, police spending is a bad indicator of safety. Despite crime rates dropping since 2001, subsequent spending increased 28 percent, adjusted for inflation, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics and the Justice Policy Institute (JPI).

“Although crime rates are at the lowest they have been in over 30 years, the number of arrests has declined only slightly,” JPI reported. “The U.S. still spends more than $100 billion on police every year.”

Critics could point to Flint’s 10.213 crimes per 1,000 people and blame its $269 per capita spending on cops, according to “Return On Investment on Police Spending,” a report by WalletHub.com. However, Detroit spends twice as much ($554) and still shows 9.692 crimes/1,000. St. Louis spends $709 per capita and remains the fifth-worst in the country.

“Much of America wrongly approaches safety at home as a peacekeeping problem: More danger on the streets must mean we need better-equipped police to impose stricter order,” reported journalist Chris Walker on the Mic.com news site. “Our communities aren’t war zones though. Throwing money at policing doesn’t necessarily make our communities safer.”

Crime is complex, affected by factors like acceptance of violence as a response or the number of juveniles whose brains and judgments are still developing and feel alternately invincible or doomed.

“Crime can be seen as a symptom of a lack of educational or economic opportunity – or of hope,” Brady says. “It’s driven by education, racism and gun violence.”

Local law enforcement is focused on shooting, which is down in a few categories from 2013: shots fired (-26 percent), people shot (-27 percent) and murders (-77 percent).

“The number of murders isn’t the best measurement of public safety,” Brady says. “From my perspective, it’s shootings. Gun violence doesn’t have to be tolerated in civil society.”

Recent Comments