A distinguishing characteristic of contemporary art is that it reveals subjects either socially marginalized or sub rosa. Many artists believe art has a moral responsibility to do so. Art that advocates for the rural, but is formally and conceptually rigorous – that uncovers the relationship between the intellect and the advancement of place, is such work. It may include projects that are contemplative and protracted, liminal, silent, or anthropological – invigorated by cultural memory, interior narratives and utilitarian design. Artwork like this provides a richer portrait of Middle America and an important alternative to the depleted specter of much contemporary art.

Coastal culture is fixated on vaguely-chic, futuristic and consumerist art production. Museums blithely assert that the city and spectacle are the defining subjects of cultural advancement and the only home for innovation. Our most powerful art institutions are equivocal about challenging that discourse. They appease audience’s passivity and exploit their distractedness by bracketing radical exhibitions with fantasy and celebrity. They ooze curatorial itinerancy and thwart a more coherent, place-oriented, stream of American narratives.

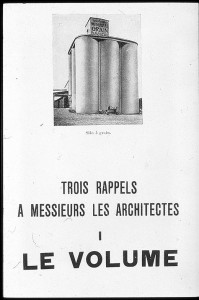

Grain silos inspired the work of Le Corbusier, 1887-1965. Le Corbusier was a Swiss-French architect, designer, painter and urban planner who was one of the pioneers of modern architecture. More than a dozen of his projects are now on the UNESCO list of World Heritage sites as “an outstanding contribution to the Modern Movement.”

The seeds of contemporary art, however, were also sewn in nature and in engineering. Grain Silos inspired Le Corbusier’s liberated forms. He believed that the materials of architecture and city planning were “sky, space, trees, steel and cement; in that order.” Frank Lloyd Wright went farther. Respect for the viewer’s intelligence and experience was built into designs that considered the social network of place and class. Despite the fact that he designed a mile-high building, Wright thought high-rises for living and cities in general were loathsome and that the nation should be decentralized to solve its economic injustices. His utopic Broadacre City plan set aside acreage for each home to grow vegetables and raise a few animals, but it also was designed to have a civic opera, sports arena, and a museum. He forecast a rural/urban dialogue and reformed our aesthetics and living spaces with principles that inland art still cultivates.

Unfortunately, rural vs. urban is still a dichotomous construction used to esteem the metropolis rather than being an integral part of a system. More accurately rural and urban are mutable, contestable things with no hard boundaries, but presenting them as fixed valorizes the harder logic and affluence of the city.

The past decade has been complicated by a Balkanization of news and entertainment. Social media has captivated insolated readers who dismiss the value of cross-cultural conversation. Mainstream news remote-senses all manner of farcical reportage – and assumes the high ground in their presumptive pluralism. The art press offers little more as it devotes itself to synthesizing and monetizing artistic expression. Why does that matter? Because culture is flux, and nations benefit from a fully reasoned debate about everywhere progress and innovation reside.

The cities with the most active arts commerce are increasingly gentrified, cloistered and unaffordable, making suburbs and rural areas progressively more representative of America. While roundly stereotyped as indistinct, undereducated and depressed, smaller communities are flexible, entrepreneurial and socially productive for emerging artists. DIY practice and a respect for manual labor is abundant in the provinces. Objects are held in high esteem. Craft and design thrives in Midwestern art curriculums. As a result inland artists have allegiances with productive communities outside the art world such as manufacturing and building trades. Inland art can’t avoid engaging local histories, partnering with other disciplines and affecting a wide range of spectators who don’t view art as amusement or investment.

If immigration (and not xenophobia) continues to trend in America, a comingling of cultures and subcultures and a re-consideration of place will compound our living art language. Where you can live and thrive will become as critical an identifier as race, sex, class or gender. Suburbs, exurbia, smaller cities and rural areas will hold a larger stake in defining culture in the future than cities, who’s art is increasingly detached, solipsistic and paid for.

4 comments for “”

Recent Comments

Paul, I appreciate your drawing distinctions between rural and urban art making. After 40 years of urban living/working and a wide range of gallery experience I find great solice in my new life as a rural artist. Among the most notable shifts in my awareness has been the liberation I experience daily which spaciousness enables in addition to the opening silence generates. Perhaps it is this very circumstance which facilitates a shift in perspective to a body centered awareness and all that it implies, in particular a shift from encapsulated thinking into the intelligence of feeling.

Thanks for your comments Tom. The ability to have a contemplative practice is rare, no matter where you live, but the opportunity to make mindfulness a subject of one’s work is a part of the allure of the rural.

Paul

Really important points you’re making here about rural versus industrial habitation and a political climates effect upon its populis, community and economic relationships, and upon the arts. Thank you for your thoughtful insight.

Thank you Suzan. I appreciate your comment and your interest. My newest column will be up in a couple of weeks and posted on my Facebook page.