PAUL KRAINAK

With 2018 winding down, I feel obliged to reflect briefly on central contemporary art figures in the Midwest. Art from the middle America differentiates itself from coastal markets via artists such as Ed Paschke, Phyllis Bramson, Kerry James Marshall and Michelle Grabner, just to draw a few names out of a hat. While there is little formal thread among these Chicago-based artists, they share something critical. Despite being widely recognized, each has resisted how art is generally promoted on a national stage. Many came to maturity before the machinery of the global art market would portray their careers. They made work that was derived from a real place and singular experiences –– narratives in the vicinity of their studios, the places they’ve worked or taught and histories they have inherited. In larger coastal metro centers the subject of art is infringed upon by the business of art, the strategies of curators and the whims of collectors who profit from monoculture. Chicago and the Midwest attract artists who make exceptional objects that are external to art-vogue.

University art departments support our leading artists and are silent partners in inland art. Images and ideas are absorbed from mentors who hand down the accounts of the ones who mentored them. It’s a more intimate sharing of ideas than academies on the coasts that are designed to feed the enormous appetites of multinational markets. The Midwest conserves and modifies tradition that is germane to identity, debate and visual intelligence. The coastal fixation for transcending the past and substituting pageantry or gloom is cultural itineracy.

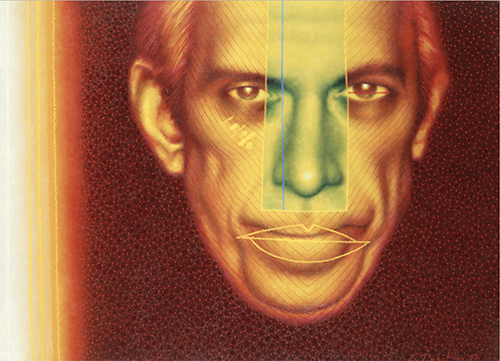

“E.P. Rouge,” Oil on linen, 1993. (PHOTO REPRINTED WITH PERMISSION, ED PASCHKE ART CENTER)

The choice to live in the present and fine tune one’s surroundings in the Midwest or other inland cultural zones is substantive and rational. That the Ed Paschke Art Center is the only Chicago exhibition space devoted to the legacy of a single artist is no surprise. His work is as esteemed equally by artists and the general public. The 14th anniversary of his death was just last week, and while much has occurred during that time, Paschke’s work seems as virtuosic and charismatic as ever. His radically electrostatic portraits of the famous and the anonymous calculated the drift towards obsession, narcissism and escapism in which we are now embroiled in so much of the mainstream. His slightly detached gaze and criticality came from being planted firmly at a distance from official tastemakers.

I had the pleasure of speaking on a College Art Association panel with Paschke in the 1980s. The subject was “The Not in New York Artist,” and it addressed the dilemma of Midwest artists leaving for New York as well as strategies for making inland America more responsive to a seriously engaged practice –– i.e. an alternative to New York City. Paschke’s blunt assertation was that he wasn’t driven to become a New York artist. He told the convention crowd that “It’s easy to be an artist in New York. Everyone there is an artist. I want to be a Chicago artist.” He preferred to labor here precisely because of Chicago’s more sober identity, and that his measure of anonymity was more valuable than celebrity. It was a perfect riposte to those who grumbled about not getting validation from a remote licensee. Paschke defied that authority, embodying the post-regional artist who defines art on his or her own terms and in relationship to where they live. His instinct that investing in place and its history held more promise was part of the debunking of New York’s citadel of place transcendence that Chicago picked apart, plank by plank in the 1980s.

3 comments for “Inland Art | A not-in-New York artist”