Agreed: Water and its safety are important to Central Illinois.

Agreed: Water is a key piece of the economic puzzle as the City of Peoria faces huge financial strains.

Agreed: Water’s place in that puzzle is determined by the Peoria City Council.

Disagreed: Just about everything else.

Over the past couple of years, the debate over public vs. private management for Peoria’s water franchise has resurfaced. The history and details are complicated. But the council’s Oct. 30 decision against “due diligence” — getting facts to decide whether or not purchasing the water franchise is a good idea — sparked outrage and vows to keep the issue alive.

The pro-public argument says ownership of the area’s water should be investigated. Water belongs to the people, so information about it should be readily available, particularly about costs. Peoria residents pay twice as much for their water as the national average. Perhaps some of that revenue could help address the City of Peoria’s looming debt crisis.

“I do think it was a missed opportunity,” said Cheryl Budzinski, who spearheaded the League of Women Voters of Greater Peoria’s effort to pursue due diligence. “Since the vote, I have had several people ask me what other new revenue sources have been offered by councilpersons. I think more people than we realized felt that due diligence was an important step for our community. It may not have worked out, but to not take that step was political and harmful to the future.”

Money figures prominently in the pro-private argument, as well. The city doesn’t have enough to investigate, much less purchase, a franchise from an Illinois-American Water Co. which consistently says it does not want to sell. Illinois-American insists spending up to $1 million on due diligence would be a waste.

“We’re looking at three-quarters of a billion dollars in debt load for the city,” said Mayor Jim Ardis. “ . . . It’s $300 million we don’t have. Is it realistic to put that on top of $500 million we don’t have in CSO (combined sewer overflow) costs and pension obligations?”

The answer depends upon who is asked.

What happened?

The winners of the latest round portray it as a slam-dunk.

“The Peoria City Council voted 8-3 not to pursue a takeover of the local water system,” e-mailed Illinois-American spokeswoman Karen Cotton. “We support the council’s vote against a buyout as it represents the 88 percent of Peoria voters who told us the City has more important priorities.”

The losers cite technicalities.

“Ardis has continually moved the goalpost,” said Terry Kohlbuss, a former city staffer who has worked with both the League and the CEO Council on the water issue. “. . . These guys don’t mind the sinking of the Titanic, as long as they’re the captain.”

As always, the devil is in the details.

Peoria’s water has been managed privately since 1889. The city has the chance to revisit the issue every five years, so efforts to regain public control resurface repeatedly. (Peorians who fear the city couldn’t handle the job might consider that timeline when they see another water main break stop traffic.) The 2018 Ardis council is not the first to decline.

Ardis has served on the Peoria City Council since 1999, as mayor since 2005. It’s roughly the same time public-water forces really got engaged. Shortly before he became mayor, the council voted to pursue due diligence on water with financial help from some of the area’s business leaders. But the city did not do due diligence, the business leaders wanted their money back, the fight ended up in court and the city is now on the hook for the original loan-plus — a tab over $2 million, increasing more than $300 a day at 6 percent interest.

This may be a drop in a $300 million bucket, but it muddies already-roiled waters, to mix even more metaphors.

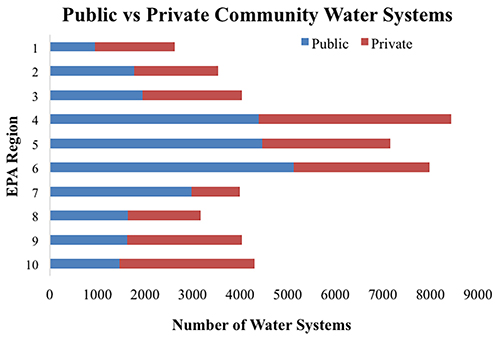

Public-water advocates note almost 90 percent of the water in the U.S. is managed by government, which can keep prices low and use the resource to lure economic development. Their estimates indicate public ownership could mean $15 million a year to this cash-starved community. Buying the water company could not only pay for itself, they say, but help pay for the $200-million-plus combined sewer overflow project mandated by the federal government.

Private-water advocates point to Illinois-American’s solid record for good water and satisfied customers. They scoff at the notion the city could handle the management, or the debt, for what may be a $300 million enterprise. Efforts to get the old loan forgiven failed, and they cited that precedent when the CEO Council offered a new $700,000 loan for due diligence now.

“You can see how both sides are reluctant,” Ardis said.

A lot of these figures may be inflated. Or low. Illinois-American has the actual numbers and does not open its books here. Appraising such a public/private entity is tricky. Pursuing due diligence doesn’t mean deciding to buy the company. It means analyzing real costs and benefits in order to make an informed decision.

The latest debate on whether or not to proceed with due diligence has been ongoing for more than a year. Yet the council ended up with a last-minute special meeting before the Nov. 2 deadline to decide. The LWVGP had raised questions about conflict of interest for both the mayor and 1st District Councilwoman Denise Moore. Both voted anyway.

And there was more than one vote that night. Council members voted 6-5 to accept money from the CEO Council to pursue due diligence. But, according to Corporation Counsel Don Leist, that means spending money in 2018 — an assumption questioned by Council member/attorney Beth Jensen — which requires amending this year’s budget. That takes eight votes.

“If he doesn’t have six votes, he says he has to have eight votes,” Kohlbuss said of Ardis. “And gets the city attorney to back him up.”

“I didn’t change that. That’s a council rule. I did not move that ball,” said Ardis.

There was more discussion, despite Jensen’s motion to call the question. It was Council Member Zach Oyler’s motion to purchase the waterworks which failed 8-3.

The pro-public water effort failed.

What happens next?

Like Gertie the Groundhog or swallows to Capistrano, the public water option can be counted upon to return like clockwork.

“What happens next is: Hit replay,’’ said Ardis. “Hopefully not with all the drama. But the process is the same.”

One definition of crazy is to do the same thing, expecting different results. Ardis said public-water advocates always say they’ll start sooner, but don’t. This time, those advocates say they will start the debate sooner. And they will prepare differently.

“It is good to continue to plan for the next four years,” said Budzinski. “IAWC had the potential to lose $15 million profit per year and was willing to spend big money to avoid due diligence. They spent some money. Whereas, our organizations do not have the budgets or the fear of losing profits. We were looking at the possibilities of a future with lower water rates, or additional revenues, and transparency in rate setting, costs, and our environmental future . . . . A full-out campaign could cost $25,000 plus. We need to start planning and collecting money.”

Tom Fliege headed up the CEO Council’s water committee. Initially, he wasn’t convinced public ownership held promise. But the more he learned, the more convinced he became. Fliege ended up giving dozens of talks to neighborhood groups and clubs in an effort to raise awareness.

“We’re being gouged,” he said. “And the people who are being gouged the most are lower-income people. Who is standing up for them? Not their council.”

He said the water committee compiled a final report including five possible courses of action. The first four are not recommended: Sue the city for improper procedure. (More division.) Say nothing further and allow Illinois-American to declare victory. (Lets the other side win on technicalities.) Initiate a long-term public education campaign. (Issues are complex and PR is expensive. Illinois-American is a $16 billion corporation.) Work within the system, as a group, to recruit new council and mayoral candidates. (Can’t do it as a 501(c)3.)

Instead, the recommended option is to “ask ourselves what we can do, as individual business leaders to act to improve our community, i.e., actually LEAD.”

In fact, that is one more thing everyone agrees on: Changing leadership on the Peoria City Council will make all the difference in the water buyout issue over the next few years.

“The next chapter of this is council elections,” said Kohlbuss. “That’s the only way this is going to get fixed.”

“Six votes changes your water rates,” said Ardis.

For more information, access these sites:

http://efc.web.unc.edu/2016/10/19/public-vs-private-a-national-overview-of-water-systems/

https://www.pjstar.com/news/20181030/peoria-council-turns-down-water-company-bid

http://www.peoriagov.org/city-council/council-meetings/

Recent Comments