PAUL KRAINAK

“When I lived on Lincoln, and then further up north on Damen, I loved taking walks at night on Ravenswood, which then was a deserted industrial strip. It’s now a Hipster haven. Thinking about this may account for my more recent work, which although still architectural does not deal with old Chicago, or N.Y. or most of industrial middle-class working America and its artifacts.” – D.K.

In the ’70s, Hubbard Street was Chicago’s epicenter of emerging contemporary art and a magnet for young artists regionally and nationally. Although just north of the river from the Loop and steps from Michigan Avenue, the zone had a radical vibe, distinct from districts on all sides. It was more than the fact that there was a pocket of six-story lofts with muscular oak pillars and raw spaces. A preponderance of low-rise warehouse buildings served as living and working studios for a growing number of artists, designers and musicians taking advantage of surprisingly affordable rents. The street was charged with a conglomeration of cooperative spaces, beauty salons, diners, photo processing houses, dance clubs and architecture studios. Harry Weese’s office was directly across from N.A.M.E. and Artemisia and just above Chicago Filmmakers. Weese published Inland Architect, a magazine I came to write for on public art. Looking east across State Street was the elevated and affluent Michigan Avenue traffic while the west gave way to low density industrial buildings and smoky sunsets.

I first visited N.A.M.E Gallery in 1976 where sculptor Dennis Kowalski was installing his first one-person show. I’m sure I didn’t grasp it at the time as it was an installation of common construction materials designed to reflect Chicago’s vernacular building methods in working class neighborhoods. And even though I just strolled in while the sculptor was working, he was totally relaxed and willing to talk. Three semi-independent wood structures easily packed the gallery’s substantial interior and we talked about them, but what I recall was the works’ palpable stillness.

At that time, Dennis was considered a kind of plain-spoken post-minimalist, but the nature of his work was not that theoretically handcuffed. He had begun teaching at the University of Illinois, Chicago where a tradition of constructivism and abstraction disputed the expressionism and imagism taking root in the School of the Art Institute and at the University of Chicago. His sensibility was embodied in a basic respect for production processes that bridged sculpture and architecture. The work was striking and muscular but grounded in a democratic vision of culture, in real sites and ordinary buildings. It embraced the modernist tenet that art should not only enhance essential experiences, it should reveal these experiences as aesthetic goals in themselves.

His constructions were reflective of a respect for engineering and design that originated from his earlier days as an architecture student. The sensibility that penetrated many of the post-minimalists was channeled primarily by an urban dialogue with links to the geometry and materials of Constructivism and the spaces of De Stijl. Kowalski’s rudimentary forms, however, would prove to be more influenced by American art studio traditions and skilled labor practices than aestheticism and critical discourse.

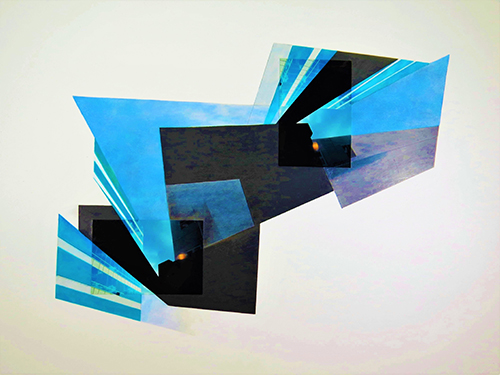

Kowalski’s most recent works are compositional detachments scrambled from actual architectural sites – consisting of diagrammatic, winged shapes that hover in vertiginous mid-flight. Spatial inversions of top and bottom, interior and exterior, flatten to imply multi-perspectival views that require formal decoding. The work echoes fragments of groundbreaking architectural studios like Koolhaus and Himmelblau whose designs are well known for bending and twisting structures beyond their traditional function or their material capabilities.

Kowalski’s organizational format also bears some interesting relationship to Chicago architect Marshall Brown’s “stealth collages.” As a designer, Brown’s formal interest lies in the possibility of contained spaces with a potential for modernist re-definition. Kowalski, however, strategically inverts representational design details, adding soft interstices and fissures that preclude the normative processes of achieving wholeness or objectness.

Moving away from categories like interior/exterior helped the artist generate hybrid images and his own method of formal division and displacement. While his early constructed assemblages and later flat work appear radically different, both reflect a debate between operation and abstraction. These aren’t the usual quantifiable experiments sculptors are drawn to as they skirt the resolution of form or the illustration of material. Kowalski works with the matter that falls through the cracks of either sculpture or architecture and notes the effects of places transfigured by time as he stresses in the opening quote. No grand themes, no spectacle – but the infinite pleasure of mastering virtual evidence and unpredictable change.

Dennis Kowalski has a show May 16 through June 28 at Gallery Studio OH, 4839 N. Damen Ave., Chicago. Opening reception is 6 to 9 p.m. June 7.

“Adelaide Window” by Dennis Kowalski, photograph and colored paper, 22 by 30 inches

1 comment for “Inland Art | Dennis Kowalski”

Recent Comments

Hi Paul, another brilliant review… Although, I think, plain spoken Dennis is definitely a keen observer of a transient human conditions in the city. A social commentator of changing times of culture, environment, perception though the materials and structural destruction and projections. Dennis I know and remember is subliminal and much more complex…