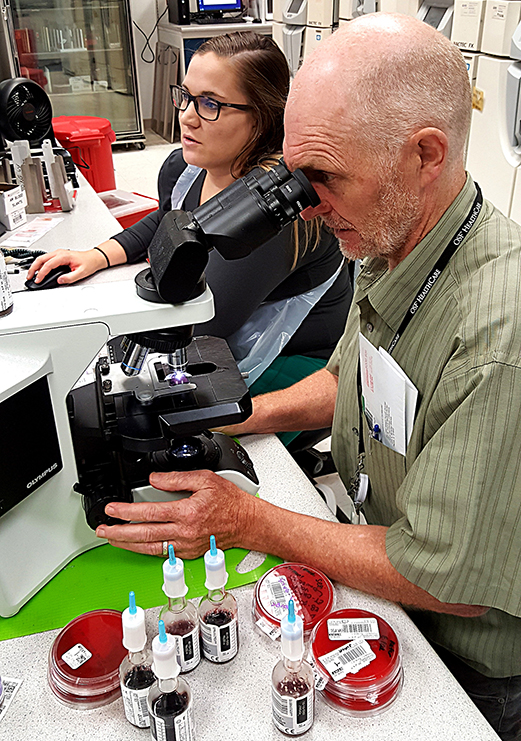

Infectious disease specialist Dr. John Farrell examines a specimen as medical lab technician Morgan Beschta looks on at the OSF System Lab in downtown Peoria. (PHOTO BY BILL KNIGHT)

People already in various medical facilities and the health professionals helping them have a new threat: a fungus named Candida auris (C. auris) that’s developed resistance to multiple drugs and is killing tens of thousands in the United States and making millions sick, says the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

This spring, the CDC confirmed cases of “pan-resistant” C. auris, a strain against which all major anti-fungals are ineffective, said Dr. Tom Chiller, who heads the agency’s fungal division.

Candida infections generally are a major cause of illness and death in critically ill patients, and C. auris specifically is an emerging fungus spreading worldwide, killing about half its victims.

A yeast, C. auris has three troubling characteristics, according to the National Institutes of Health: It’s often misidentified; its antifungal resistance makes it challenging to treat; and unlike other Candida species, it can survive on surfaces for weeks, and on skin for months, allowing further transmission.

There are about 50 Candida species and 20 strains of Candida auris, says Dr. John Farrell, Director of Microbiology and Serology at the OSF System Lab in Peoria.

“I was first alerted to it when the CDC in 2016 sent out something urging more quality control for C. auris, which made me curious,” he said.

Besides the United States, the CDC reports that C. auris has been reported in dozens of countries in Africa, Asia, Europe, the Middle East and South America.

The Illinois Department of Public Health (IDPH) has said “numerous” medical facilities have reported 158 C. auris cases since 2016, about 100 in Chicago and the rest outside the city.

“Fungal infections caused by C. auris, and similar infections have the potential to cause serious illness, are often resistant to standard medications, and continue to spread in health-care settings,” says IDPH Director Dr. Ngozi Ezike.

At least 557 cases of C. auris have been reported in the United States, mostly in Illinois, New Jersey and New York, but there haven’t been cases acknowledged in central Illinois.

Yet.

“It’s going to be endemic,” says Farrell, who’s also a professor of clinical medicine at the University of Illinois College of Medicine. “It’s inevitable.”

There may have been more fatalities; a precise count is difficult since many patients also have other serious ailments. C. auris tends to infect people with other conditions: post-surgical patients, diabetics, people with compromised auto-immune systems, and those recently treated with antibiotics and anti-fungal medicines. Other risk factors include patients using feeding tubes, catheters, IVs and ventilators.

Although C. auris was detected in 2009 by physicians in Tokyo examining a 70-year-old woman, it’s probably existed in some form for thousands of years, says the CDC’s Chiller, but the increased use of chemicals in agriculture correlates to its increasing resistance to extermination. For example, 80 percent of all U.S. antibiotics (17,000 tons) are used on livestock, according to researcher Alex Liebman of the Lurralde conservation and environmental protection group in Chile, and massive amounts of pesticides (fungicides, herbicides and insecticides) also are used on crops.

Today’s main fungicides were rarely used before 2007, according to Matt Fisher and colleagues, writing in Science magazine, but about 10 years ago, 30 percent of corn, soybean and wheat fields –– 80 million acres –– had fungicides applied.

“In a cruel irony, fungicide application places evolutionary pressure on pathogens to develop resistance at the same time that industrial management provides the near-perfect conditions for fostering and spreading these virulent mutations,” Liebman says.

Farrell sees a parallel between the C. auris situation and the 2009 pandemic of swine flu, a virus that sickened many.

“We were lucky more didn’t die,” he says. “Farms where a lot of antibiotics and pesticides were used, keeping livestock well and weeds out of the fields meant a mixture [of factors], especially at pig farms. Pigs are the perfect vessel. From the same ecosystem [came] runoff and waste, which flowed into streams, and we got novel mutations: a new flu.”

Now, some scientists see answers to overuse of pesticides and drug-resistant bugs such as C. auris in crop rotation and cover cropping, but solutions frequently are limited to combining current fungicides. Also, the current Environmental Protection Agency may relax pesticide regulations, causing some experts to criticize government’s deference to corporate interests.

“What’s in the industry’s best interest will win out over public safety 9 times out of 10,” Nathan Donley, a senior scientist at the Center for Biological Diversity, told The New York Times.

Meanwhile, the fungus moves within medical facilities by remaining on equipment or surfaces, spreading by direct contact or even by the routine flaking of skin cells. Symptoms of Candida infections include fever and chills that persist after antibiotic treatment for a suspected bacterial infection. The CDC says C. auris can be on the body without the person showing symptoms, making identification challenging before appropriate treatment can start.

During or after treatment, disinfection is needed –– and problematic. Protocols range from disinfectants and antiseptics to alcohol-based sanitizers and ultraviolet lights. Chlorine products help, but there’s little certainty on disinfectants’ effectiveness

“There is no established environmental cleaning method in controlling the spread of C. auris within health-care facilities,” according to Tsun Ku and colleagues, writing in PubMed Central.

Ninety percent of c. auris is resistant to one fungicide, and 30 percent to two or more, according to researchers, but there’s no reason to panic, Farrell say.

“It’s not a cause for alarm,” he says. “No C. auris strain is resistant to everything.”

Further, the OSF System Lab – with some 250 staffers serving 124 locations, including 13 hospitals, 18 managed-care locations and 11 centers for health – can handle such incidents.

“Our lab is able to recognize it,” Farrell says. “This is a reference lab; we have the expertise. A community lab can’t distinguish it to a specific level.”

Also, Farrell is skilled; last month the CDC published an article by Farrell and colleague Therese Woodring about a fatal septic transfusion reaction in Peoria.

“The rub [with C. auris] is balancing risk and benefits” Farrell says. “It may require a more toxic medicine and a patient who’s going to need it may be fragile.”

The emergence of C. auris isn’t the first such threat, but they’re becoming uncomfortably common. Humans are inadvertently, if repeatedly, contributing to the evolution of superbugs, the informal term for ailments that have become resistant to previously effective remedies. They include Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus Aureus (MRSA) and Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE).

“C. auris is eerily similar to [the rise of] CRE,” Farrell says. “CRE suddenly showed up in London in an intensive-care unit that had to be shut down, then in Brooklyn, where it couldn’t be eradicated even after the outbreak was controlled.”

CRE is a group of gut-dwelling bacteria that no longer respond to many carpapenems, considered “last-ditch” antibiotics. First sighted by the CDC in 1996, it was identified in the U.S. in 2001 and by 2013 the CDC dubbed it a “nightmare bacteria.”

“It’s the exact same situation we saw with CRE,” Farrell says. “You have a superbug.”

Recent Comments