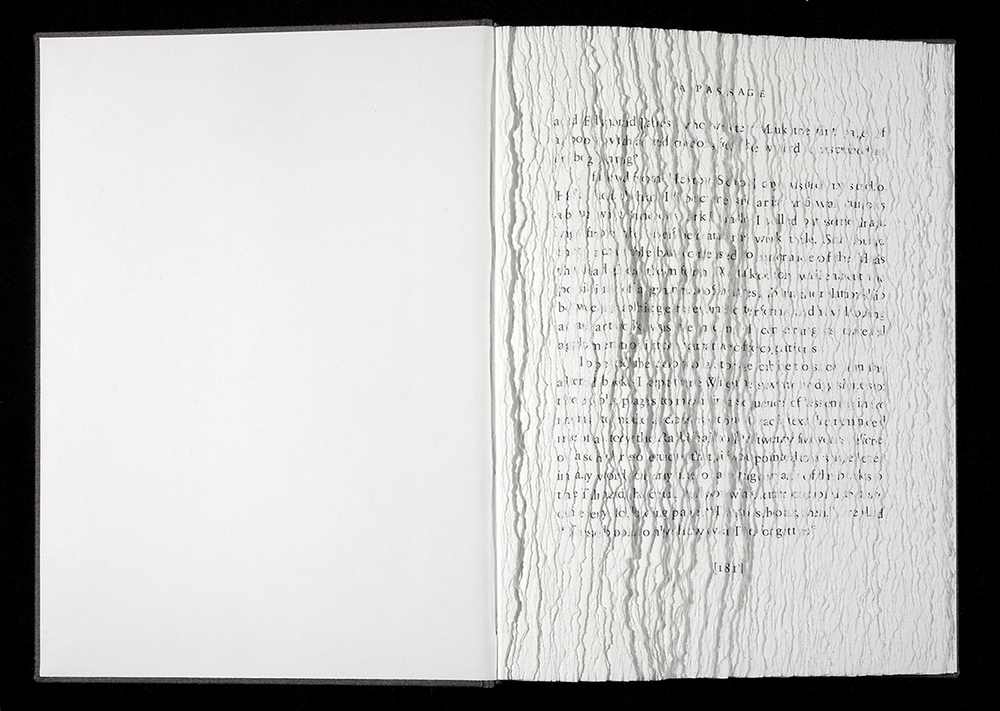

Buzz Spector, “A Passage,” 1994. (SUPPLIED IMAGE)

PAUL KRAINAK

Spector’s practice may comprise curious taxonomies like the ones Michel Foucault noted in “The Order of Things.” Foucault referred to Jorge Luis Borges’ fictional “Chinese encyclopedia” that classified animals as “those belonging to the emperor,” “drawn with a very-fine camelhair brush,” and “from a long way off look like flies” among others. Foucault was struck by the taxonomy’s brilliant unorthodoxy, writing that “the exotic charm of another system of thought, is the limitation of our own.” In the process of alternatively organizing the bibliographic and pictographic, Spector uncovers the occasional foreignness of abstraction and re-routes objects morphologically. The takeaway is that our familiar rational classifications are likewise exotic somewhere, or soon will be.

In Spector’s modification’s of language, materials and images, he bares sub-text – pictures that from a long way off look imperial, but at close range we observe that incongruity and ordinariness can be aligned and enclose their own beauty. His skill for inspecting details stems in part from literally dissecting the framework of texts. Add to that the ocular dexterity ordinarily demanded of drawing, collage, and especially the print –– whose ideal frame is no frame. It’s not just that Spector’s work is a hybrid. It’s reflective of a turn in art that refutes the autonomy of both the text and image in pre- and post-modern.

Some of Spector’s most striking work is also a form of un-architecture. He arranges large selections of hardbound books in sloped, curving wall forms that rebuff the venerable method of arranging them primarily by content. They affirm that it’s logical for artists who have assimilated any degree of deconstruction and intervened in curatorial strategies to encroach on libraries’ alphabetical distribution and decimal system. Spector reclaims collections, gets them off the shelves so we can walk among them decrypted. Temporarily freezing a tide of information, archives are secured from their institutional confinement, sidestepping sobriety and extending refuge. Consequently, and ironically, content is temporarily deferred.

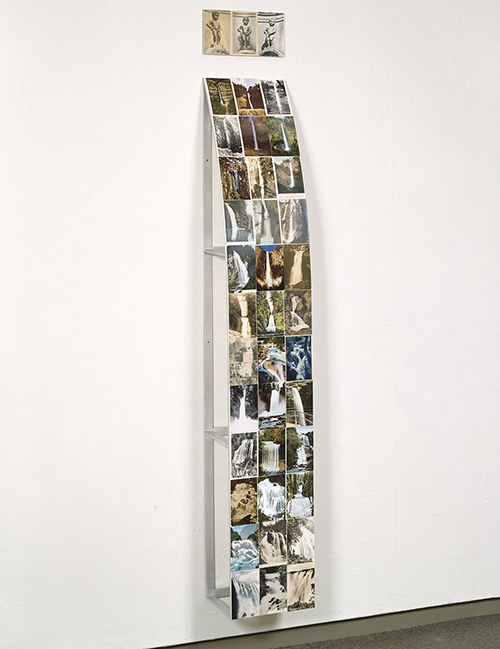

“Waterfalls” is an individual wall-piece that raises eyebrows about nature in the 17th century Brussels fountain statue “Manneken Pis.” It caricatures the sentimentality of popular tourist destinations, ones which lend themselves to an exaltation of classical art and antiquities as well as those that romanticize and objectify nature. In Spector’s fountain three postcard images of the memorable peeing boy sculpture stand above a human-scale cascade of 36 natural waterfall images. The postcards are affixed to a gently bowed aluminum frame that spill the images forward, connecting with our bodies and with the status of sculpture. The work recalls the ramp contours of his stacked book installations. A floating grid designed from skillfully arranged postcards digitalize water and submerge personal inscription in a way that the installations inter literature.

Before recalling Michel Foucault’s seminal text, I felt Spector’s sensibility was more aligned with Joyce or Stein, i.e. more about de-composing, displacement and deferral. The episteme of the modern, its persistent shaking up of vision and speech and endless self-analyses is academically determined. Spector’s work, however, feels like scholarship that is both subject and the analyst, story-teller and censor. Message fragments appear in his books, like “A Passage,” to reveal spatially degraded views of each page –– as if he was designing in reverse and relishing the epigraphic mischief. While asserting the range of the ordinarily restrained physicality of books, “A Passage” substitutes an alternative model of Joyce’s time-expunged prose; every thumbed leaf bears the aesthetic DNA of the whole book. Spector thrives in his free space carved out between the linguistic and the graphic, a dimensionally unfettered site for connecting other dots between the apprehending eye and the christening tongue.

“Alterations”, a 40-year selection of Buzz Spector’s work on paper opens at the St. Louis Art Museum Nov. 20 and runs until May 31, 2021.

Buzz Spector, “Waterfalls,” 1991. (SUPPLIED IMAGE)

3 comments for “Inland Art | Buzz Spector”

Recent Comments

Great piece of writing. It illuminates Spector’s work and brongs clarity to what can sometimes seem difficult to penetrate. Thanks for this key.

Thank you Guy!

Fantastic insightful writing. Explains the Spector’s work beautifully.