Despite the isolation needed in a pandemic, some are working for others, even if it’s at a safe distance.

A garage outside Pekin is where Tazewell County Mutual Aid constantly fills and empties shelves of material for central Illinois neighbors. A recent “wish list” for items to be gathered and distributed includes powdered milk, dish soap, quarters for laundromats and gift cards (“no more than $25 increments”).

Mutual-aid organizations are grassroots groups that try to take their community’s welfare into their own hands, bridging gaps in necessary goods and services. The local network was founded a year ago this month, when COVID-19 surged but aid didn’t.

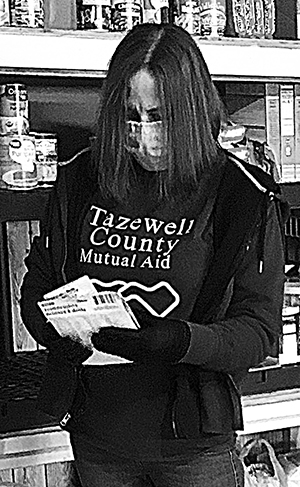

Erin Brown, founder and local spokesperson for Tazewell County Mutual Aid, sorts requests for assistance. Currently, requests are increasing for coats and groceries. (PHOTO BY BECKY ROLLINGS)

“I feared and anticipated what the pandemic would do to folks,” says Erin Rockhill Brown, a 52-year-old Tazewell County native who’s worked in education, social services, childcare and writing.

Brown has launched and helped with similar projects and been recruited into similar projects before but says this was hard to get going at first.

“In the beginning, we had difficulty finding folks in need of assistance,” she says. “I was the founder of our network and woefully lacking in the skills needed to put the word out.”

Lacking an identity and reputation, TCMA started slowly, but caught on through “word of mouth, social media, and referrals from similar groups,” she says, mentioning Enough Stuff Thrift Shop and Community Space, Porch Pantry, and 100+ People Who Care/Tazewell County.

When Cindy Klingbeil became Brown’s partner in July, activity accelerated.

“Thank goodness she joined, because she possesses organizing skills that I don’t,” Brown says. “We complement each other and are far more effective together [and] we began to receive requests for assistance and offers of assistance.”

Often structured informally, mutual aid doesn’t work top-down, but horizontally, and it’s been necessary to show people that it’s neither judgmental nor “charity,” Brown says.

“We’ve received messages from folks who are ashamed to ask for assistance, [but] our motto is ‘Solidarity, Not Charity.’ We make clear that the network is dependent upon all of us,” she says.

“One person who felt ashamed at first had prided himself on being self-sufficient. [Since,] he’s collected and distributed produce, performed more wellness checks than I can count, cooked meals for his neighbors, and is a wonderful asset to the network.”

Although the pandemic has created such responses, some point to similar approaches in post-Hurricane Maria Puerto Rico in 2017, about which anthropologist Isa Rodriguez-Soto wrote, “Only the people can save the people.” Decades before, the Black Panthers provided free breakfasts for kids who otherwise went without. And more than 100 years ago, zoologist and philosopher Peter Kropotkin wrote about people joining forces to help each other.

“It is not love and not even sympathy upon which society is based. It is the conscience –– be it only at the stage of an instinct –– of human solidarity,” he wrote in 1902. “It is the unconscious recognition of the force that is borrowed by each man from the practice of mutual aid.”

In fact, the idea goes back centuries. In the Bible, St. Paul in Romans writes, “Let us then pursue what makes for peace and for mutual upbringing.”

A 2020 book by lawyer and Seattle University professor Dean Spade, “Mutual Aid: Building Solidarity During This Crisis (and the Next),” presents principles, one of which is “solving problems through collective action rather than waiting for saviors.

“More people are learning how to organize mutual aid than have in decades,” Spade said. “This is a big chance for use to make a lot of change.”

TCMA’s network comes from Tazewell, but also McLean, Peoria and Woodford Counties, says Brown, who says its dozens of participants –– contributors and recipients –– make a diverse group.

“Members include people of every age,” she says. “Some live in houses, some in apartments, some in mobile homes, and some outdoors. One lives in a long-term care facility.”

Some are workers, others retired or jobless; many have disabilities and some have serious illnesses.

“Several are veterans,” she continued. “Some of us are Republicans, some are Democrats, some Independents, and some Democratic Socialists. Some are convicted felons; one is a retired police officer. Most of us are White, some are Latina/Latino, and some are Black.

“We all look out for each other in whatever ways we can and accept assistance as needed.”

A challenge is keeping up with different needs.

“We’ve learned to adapt from week to week to what is most needed,” she says. “Right now, we’re receiving requests for clothes and food more than for anything else. It was daunting at first, but we’ve found a rhythm.”

Besides groceries or coats, people need personal hygiene supplies, cards to buy gasoline, temporary indoor shelter, and more.

Sometimes, the effort can seem overwhelming, Brown concedes, “usually when we have difficulty recruiting delivery drivers.

“It’s definitely easy to feel happy and hopeful about when people in our network can come together safely to actually hang out and have more traditional friendships,” she says. “We have made friends, and the conversations are often hilarious.

“Laughter and fun don’t seem like basic needs to many people,” she adds, “but they are.”

Recent Comments