WILLIAM RAU

For there is hope of a tree, if it be cut down, that it will sprout again, and that the tender branch thereof will not cease. Though the root thereof wax old in the earth … through the scent of water it will bud, and bring forth boughs like a plant. Job 14:7-19

Before industrialized or clear-cut forestry and its tree-planting imperative, pre-industrial peoples repeatedly coppiced regrowth from tree stumps for carbon-neutral firewood and building materials (Rackham). Roots did “wax old.” In 2012, UK’s Westonbirt Arboretum coppiced 60 poles from a small-leaf linden with a 43-foot diameter. Tree DNA proves the trunk is from one tree, possibly a sprout when Jesus walked the earth.

For millennia, populated areas of Europe managed coppiced woodlands interspersed with naturally regenerating trees. Thus, when Julius Caesar invaded Britain in 55 BCE, southeast England’s countryside was mostly densely-settled farmland with some managed woodland. Contemporaneously, Amazonians were managing forests to support large populations through permaculture and crop production (Chazdon). Amazonians transformed infertile, acidic forest soil with charcoal- and middens-enriched “Indian black earth” to create forest-interspersed, agricultural plots.

Nor were there ancient, extensive forests when 17th-Centuary European settlers arrived on our east coast. Beginning 200 years earlier, Conquistador-spread smallpox killed 90% of roughly 60 million pre-1492 Indians (Koch), a population rivaling Europe’s. Trees then overgrew 135 million acres of abandoned farmland, and tree-accumulated carbon helped drop temperatures in the 16th Century’s Little Ice Age. Settlers moved into largely-depopulated, second-growth forests, not ancient wilderness.

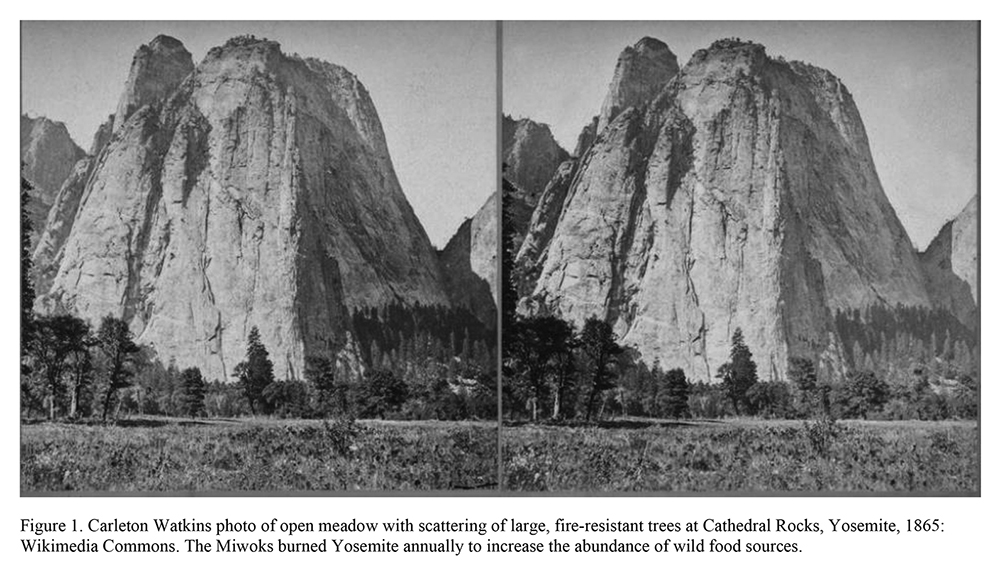

Nor were our national parks wilderness or “unspoiled” before their creation. Miwok Indians, for example, fired Yosemite Valley annually to maintain large, productive meadows (Fig. 1); yet, John Muir claimed the Miwoks had “no right place in [Yosemite’s] landscape,” and they were forcibly evicted (Johnson) to make a tourists’ playground (Gilo-Whitaker). Gorgeous photos: ugly backstory.

Trees possess irrepressible fecundity. Fence farmland near forest (the deer problem) and leave it fallow. Tree sprouts will fill it quickly. “In ten years it will be difficult to reclaim,” Rackham asserts; “in thirty years it will have ‘tumbled down into a woodland’.” Like clockwork, Yosemite’s park-like meadows were filling with trees, along with much flammable brush, 30 years after the Miwoks’ extirpation.

Why then the calls to plant? Natural regrowth does not square with modern forestry’s mechanized tree harvests nor does it permit carbon-offsets for governments and energy companies. Large land grabs for ineffectual carbon offsets, however, could threaten future food security.

Destroyed ecosystems cannot regenerate naturally, but it is not always a forest that is destroyed. Illinois pioneers plowed under much more prairie and drained more wetland than they cut forest. We therefore need ecological restoration for annihilated prairies and wetlands as well as temperate and tropical forests. Such efforts, however, face many difficulties and require their own essay. Therefore, let Oliver Rackham, England’s foremost woodland ecologist, have the last word on tree planting:

“Planting is not conservation, but an admission that conservation has failed. One can be a lifelong woodland conservationist but never plant a single tree.”

Next column: can tree planting extend environmental equity across our city neighborhoods?

References

Chazdon, Robin L. 2014. Second Growth: The Promise of Tropical Forest Regeneration in an Age of Deforestation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

Gazette & Herald. 2012 (Nov 13). National Arboretum’s lime is one of the oldest trees in Britain; https://www.gazetteandherald.co.uk/news/10043199.national-arboretums-lime-is-one-of-the-oldest-trees-in-britain/

Gilio-Whitaker, Dina. 2020 (Mar 1). The problem with wilderness. UU World; https://www.uuworld.org/articles/problem-wilderness

Johnson, Eric Michael. 2014 (Aug 13). How John Muir’s Brand of Conservation Led to the Decline of Yosemite. Scientific American; https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/primate-diaries/how-john-muir-s-brand-of-conservation-led-to-the-decline-of-yosemite/

Koch, A. et al. 2019 (Jan 25). Earth system impacts of the European arrival and Great Dying in the Americas after 1492; Quaternary Science Reviews; https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0277379118307261

Rackham, Oliver. 1990. Trees and Woodland in the British Landscape. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Recent Comments