MIKE MILLER

If you have walked any of the trails in our woodland parks around central Illinois, you will understand how walking a straight line is rather difficult. Steep hills, deep creeks and ravines, and dense vegetation make wandering cross-country a difficult proposition. Add to this the difficulty of keeping on a true compass bearing, while measuring distance with a 66-foot iron chain made up of 100 links. To be able to do this with any degree of accuracy, these surveyors were very skilled. Today, we still use these lines that they laid out more than 200 years ago.

The physical hardships the surveyors had to endure, year-round in the wilderness, would have been immense. Covering close to 20 miles each day on foot, sleeping in tents, having to regroup, move camp and all of your supplies on a regular basis. Through cold, rain, heat, and terrain that would make a modern mail-carrier cringe, it couldn’t have been an easy life. On the other hand, they had a front-row seat at the exploration of a landscape before it was altered by modern development. Today, less that 1% of Illinois looks like it did when the surveyors walked their section lines. Their efficiency at surveying made it possible for land to be sold, and ultimately altered by the new owners.

Beyond laying out the section lines, the surveyors were also responsible for documenting what type of area they were walking through. They had a list of short-hand descriptions for land. While they surveyed a line, they would identify whenever the vegetation changed along that line. For instance, when they left a forest and entered a prairie, they would identify at what point along their measurements that this happened. When they came to a corner of a section, and were in a woodland, they would take measurements to the nearest trees from that point and note the compass headings of those trees, and identify the species. This allowed the section corner to be “triangulated” by future surveyors. If they were in a prairie and there were no trees, they would build a rock carne, if rocks were available, or set a wooden stake on a dirt mound. They would also note whether an area was suitable for cultivation, or if there was plentiful timber suitable for harvest.

It is these notes about habitats, tree species, and other general observations that interests ecologists today. While the GLO Survey was designed to facilitate the sale and development of land, it also created a blueprint of what the state of Illinois was like 200 years ago. Maps would later be made from these field notes that show us the extent of forests and prairies across the state, what types of wetlands existed, and what species of trees were common and how far apart they grew in our woodlands. It is a look back at an Illinois before 99+ percent was altered by human activity. In many ways it has become a blueprint for the restoration of these habitats as well.

I recently looked back at a section line that was surveyed on January 30, 1819. It is a section corner that lies along the boundary of the Peoria Park District’s Singing Woods Nature Preserve. In the field notes, the surveyors write “Set a post at the corner of section 8, 9, 16 & 17. From a White Oak 12in diameter bearing N50˚W, 24 links, and White Oak 15in diameter, S55˚E, 14 links. Land very hilly, poor soil unfit for cultivation, timber oak and hickory, no undergrowth.”

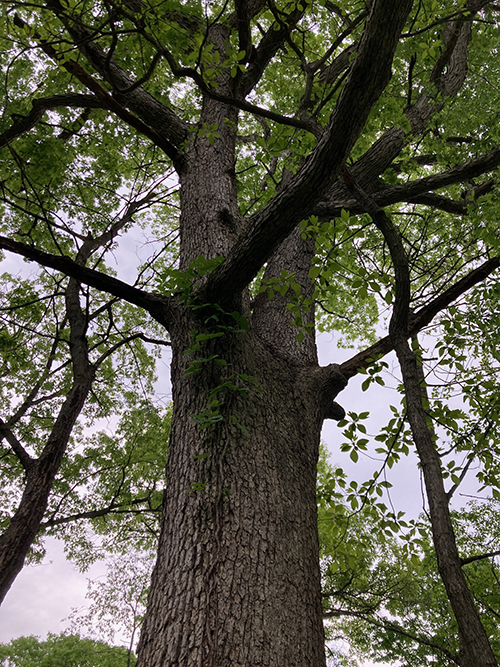

That same corner today is now under a tall powerline, and none of the original witness trees still stand. However, the survey crew also noted that as they were walking south along that same section line, approaching the corner, that they came across an 11-inch diameter White Oak, directly on the survey line, at 71.5 chains. That oak is still there. Today, it is 32 inches in diameter. A tree that, in its youth, was observed by a surveyor on a cold winter day. If only that tree could talk. Think of the stories it could tell!

1 comment for “Nature Rambles | Lines of our landscape laid out long ago”

Recent Comments

Great story. Great history. Almost romantic.