What’s worse than being sick and tired is being dead.

What’s worse than being sick and tired is being dead.

It’s OK to be curious or concerned about monkeypox, an emergency. But it’s far less contagious than COVID-19 (only about 12,000 monkeypox cases have been reported, and no deaths).

And COVID is still killing people.

Nationally, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports COVID has infected 92.8 million in the United States and killed 1 million Americans since 2020. More than 80% of all COVID cases since then could occur this year, according to the New York Times’ David Wallace-Wells.

This summer’s dominant BA.5 variant — in Illinois, almost two-thirds of COVID cases are BA.5, CDC says — has resulted in new infections up 20% in weeks, 40,000 hospitalized, and deaths rising. Within this very infectious mutation, even masked people in closed spaces for a long time are at risk. “This post-vaccine phase of COVID is worse than many expectations,” said George Mason University professor Tyle Cowen. “More than 300 Americans, and sometimes as many as 400, are dying each day.”

Virus expert Eric Topol of Scripps Research told Politico that BA.5 is “the worst version of the virus.”

BA.5’s symptoms are like allergies or sinus viruses: a sore throat, runny nose, congestion, but it’s serious.

“Although it may feel like COVID is now like annual flu, data show it is still causing more hospitalizations and deaths than the flu,” commented Yale immunologist Akiko Iwasaki.

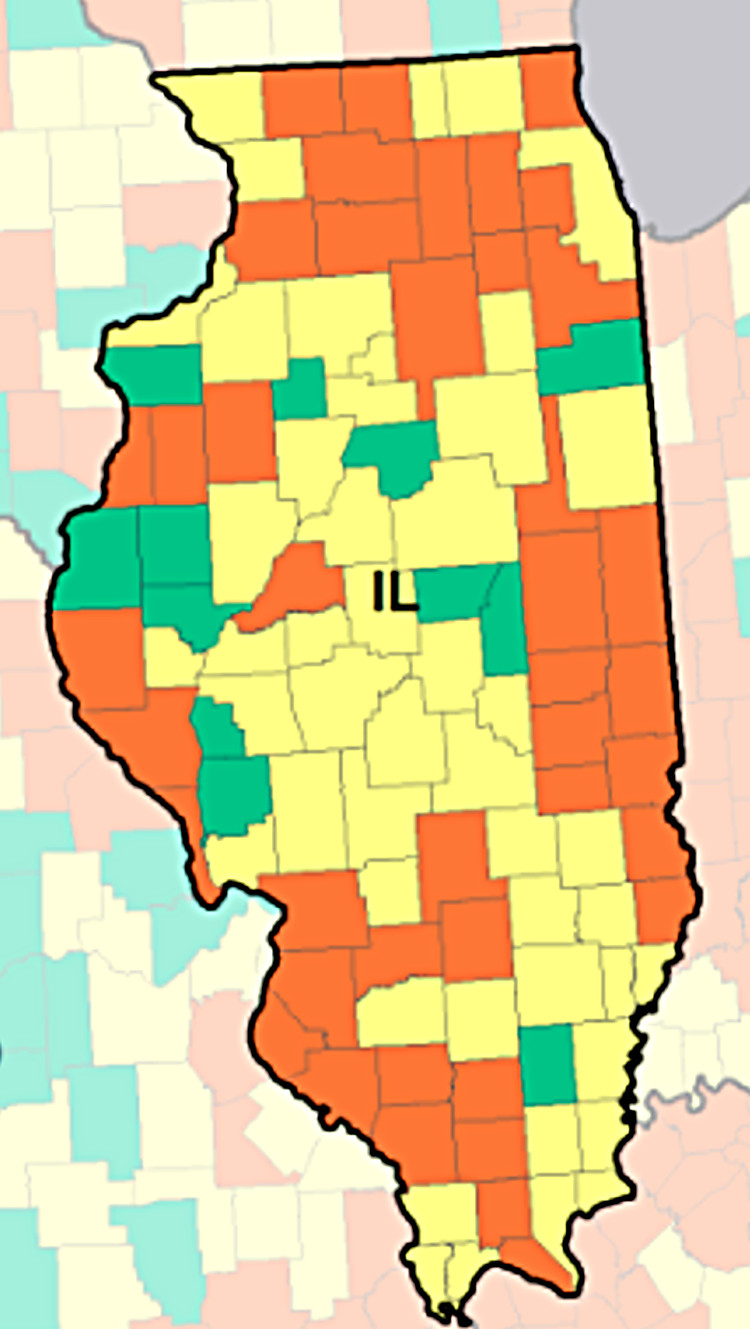

Last month, the CDC reported 27,406 new cases in Illinois and increases in hospitalizations (to 13.1/100,000) and deaths (to 1.1/100,000). In west-central Illinois, community levels are high in Knox, Mason and Warren counties; medium for Fulton, McLean, Peoria and Tazewell; and low for Stark and Woodford. (See map.)

Besides repiratory distress, COVID’s long-term effects can damage organs including the heart and brain, and the immune system.

“We are still learning a lot about the long-term effects of COVID,” says Peoria City/County Health Department Administrator Monica Hendrickson. “We have learned so much globally about impacts to the circulatory system (increased risk of blood clots) to COVID fog, and overall fatigue.”

Effective tools exist

Scientific advances have helped, Hendrickson says.

“We have learned a lot and developed multiple tools,” she says, “to assist in responding and treating COVID — rapid testing, vaccinations, boosters, and treatment — both medications such as Paxlovid but also care models needed in hospital settings. We continue to move closer to endemic phases, but I would just caution to remain optimistic. We are dealing with a virus and it doesn’t play fair.”

Yet there’s little sense of public urgency.

Another mask mandate or closing stores are doubtful, and the CDC eased guidelines on social-distancing, testing, contact-tracing and quarantines. Both K-12 schools and colleges are relaxing precautions. In Illinois, the state made available the University of Illinois’ saliva-based SHIELD testing, which 258 districts used last year. But fewer than 180 are participating now — none in central Illinois, SHIELD spokesman Steven Russell told The Community Word.

CDC recommendations haven’t always helped.

“Many people find the CDC recommendations confusing,” Hendrickson says. “CDC is providing guidance that is changing as more data and understanding is gained, the landscape over the course of the pandemic changes with new and improved interventions, vaccines and medications, and the CDC is balancing the impacts of the virus against creating secondary health issues and burdens.

“We all have different levels of risk and different willingness to accept risk.”

(In fact, last month CDC director Rochelle Walensky called for the agency to be revamped after an external review found it failed to respond quickly and clearly to COVID, and she faulted the agency for acting too much like an academic institution focusing on producing “data for publication” instead of “data for action … For 75 years, CDC and public health have been preparing for COVID-19, and in our big moment, our performance did not reliably meet expectations,” she said.)

Health officials expect a major surge this fall, and the Biden administration hopes to offer updated boosters within weeks. But “if eligible, people should not wait to get a booster,” Hendrickson says. “With the variants being highly transmissible, you want to minimize the risk of severity — meaning likelihood of hospitalization. Vaccines continue to demonstrate their ability to prevent extremely severe illness.”

Fatigue or surrender?

Now in Year 3 of the pandemic, denial of the danger persists despite the obvious: No one’s immune. COVID has sickened President Biden, Gov. Pritzker, and even Dr. Anthony Fauci, the nation’s top federal infectious-disease expert. “You can’t deny reality,” Fauci said.

Ongoing vaccine hesitation, suspicion or doubt contributed to just 69.5% of Illinoisans being fully vaccinated, according to CDC data.

Health officials are boxed

in, buffeted by business, politics and an impatient public feeling “COVID fatigue” at safety measures

“We have seen this for some time and (it) tends to cycle,” Hendrickson says. “Much of the ebb and flow relates to community mitigations, levels of virus, variants, access to vaccine/medication and on personal experience with COVID.”

The future is cloudy.

“Coronaviruses have always been circulating through the globe in some variation,” she continues. “But with this new virus and its variants, it is starting to mimic how we see, respond, and think to that of influenza.”

Officials such as epidemiologist Céline Gounder of the Kaiser Family Foundation say that by year’s end the country could see annual COVID fatalities reach between 100,000 and 250,000 deaths, making COVID the deadliest infectious disease.

“It’s important to realize that the virus is not going away and will remain a risk for the foreseeable future,” said Jennifer Nuzzo, an epidemiologist and director of the Pandemic Center at Brown University School of Public Health. “Getting infected is not inevitable, but ultimately it does come down to a trade-off: How much are you willing to give up to lower your risks of infection and for how long?”

Recent Comments