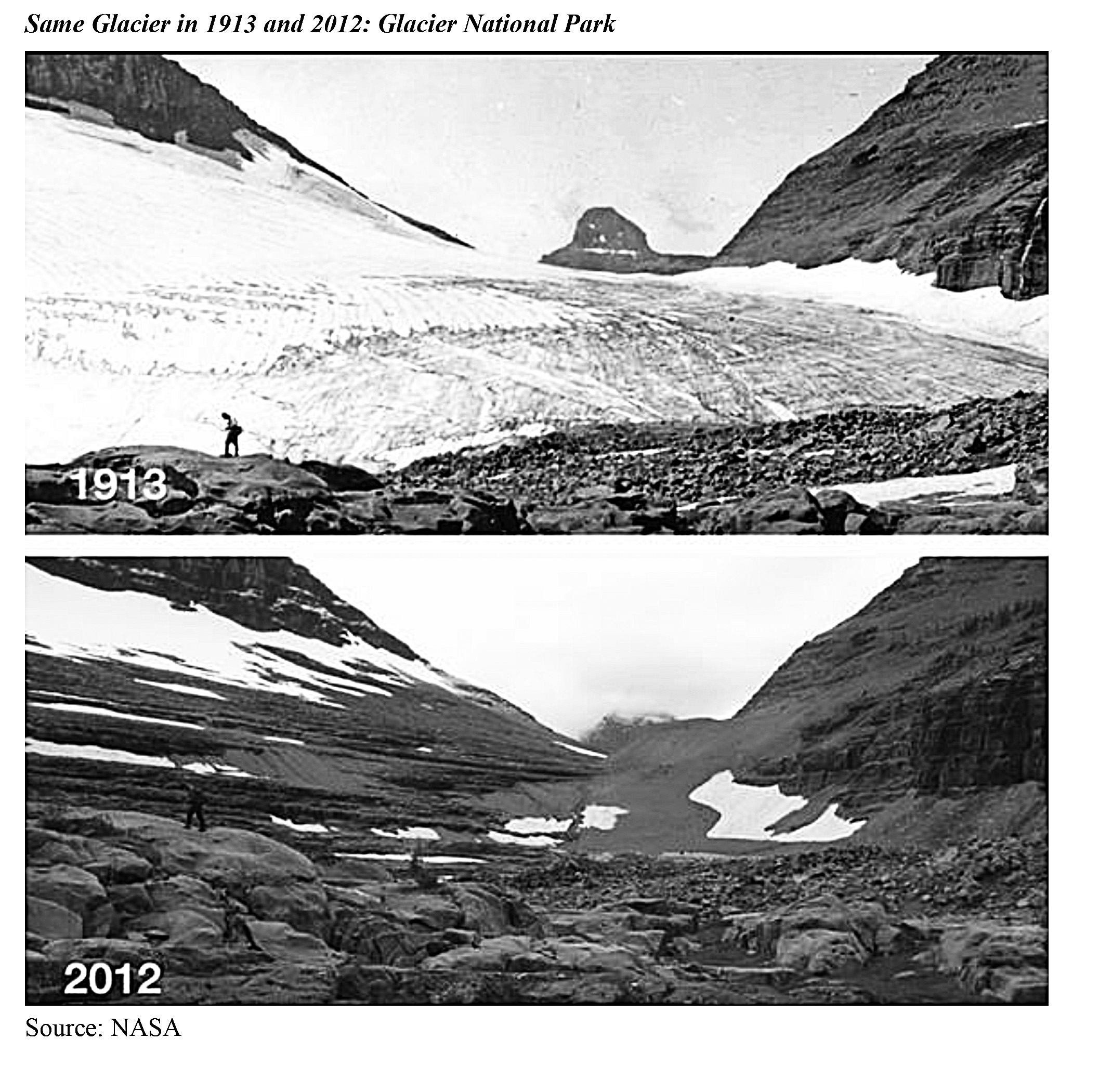

Last month I explored Greenland’s and West Antarctica’s accelerating ice loss. Both are approaching tipping points beyond which continuing ice loss becomes irreversible. Yet, these glaciers are so massive that it’s hard to imagine them withering away. For that task we can turn to mountain glaciers, such as Glacier National Park. In 1850, 150 glaciers covered the Park; by 2020 only 26 remained — a loss of 82% of the Park’s glaciers (Milman). In several decades, possibly as soon as 2030 (NASA), the Park will be incorrectly named because all the glaciers will be gone.

Sea level rise is the glacier-related issue attracting the most attention because more than 600 million people live in low-lying coastal areas. Eventually, many will have to move to higher ground. Thus, sea level rise may set into motion the largest mass migration in human history. Remarkably, Americans are still moving to coastal areas that will eventually be submerged.

That’s not all. Loss of glaciers will also degrade or destroy ecosystems on which animals and humans depend. Consider tundra reindeer who feed in the winter by rooting through dry, powdery snow to reach lichen. With temperatures rising, rain in the Artic will become fairly common in the future with follow-on frigid temperatures turning rain into ice sheets. Will reindeer be able to break through layers of ice to reach lichen, or will there be mass starvation (Carringtion)? Will Dasher, Dancer, Prancer, and their sleigh mates fade from memory along with disappearing snowy Christmases of seasons past?

Humans will also take big hits. Peru’s population, for example, is concentrated in cities along its arid coastline, a legacy of Spanish colonialism that has turned Peru into South America’s most water-scarce nation. The Incas never located cities on its water starved coast. In contrast, Peru’s capital, Lima with 12 million people, has become (after Cairo, Egypt) the second largest desert city in the world. And the flow of Lima’s three small rivers provides only a trivial fraction of the flow of the Nile. Supplied by glacial melt, these rivers are dependent on orderly, gradual melting — and there’s the rub. The area occupied by Peru’s tropical glaciers has declined 40% since the 1970s and the pace of loss is increasing. The amount of glacial water provided to bone-dry Peruvian cities is both declining and becoming more erratic with spring floods from too rapid ice melt followed by reduced summer flow.

One of the functions of mountain glaciers is to regulate the release of meltwater. Mountain glaciers act as giant water batteries. Falling snow is turned into ice during the winter. Warm-weather melt then gradually meters out melting ice when it is needed most: during Peru’s five-month dry season. Glaciers as vast water batteries keep Peru’s rivers flowing during the dry months. Sadly, there is less and less ice to fuel this natural, no-cost water storage/release system, an outcome that may soon threaten the lives and livelihoods of millions of coastal residents.

There are means to adapt, at least in part. Next month we turn to another natural water battery that will play a major role in addressing Peru’s water woes: the pre-Incan mamanteo or amunas water system.

References

Carrington, Damien. 2021 (Nov 30). Rain to replace snow in the Arctic as climate heats. Guardian.

Kormann, Carolyn. 2009 (Apr 9). Retreat of Andean Glaciers Foretells Global Water Woes. Yale Environment 360.

Milman, Oliver. 2021 (Aug 25). US Glacier national park losing its glaciers with just 26 of 150 left. Guardian.

NASA. 2016 (Jun 5). Glacial Change in Montana’s Blackfoot-Jackson Basin; NASA.

Recent Comments