People of a certain age may hear “Pleasant Valley” and think of the Monkees’ ’60s musical-comedy TV show, but Pleasant Valley School District 62 sees no laughing matter in meeting teaching obstacles some might feel are insurmountable (though it has expanded music offerings).

One challenge: 99% of students here come from low-income households. That’s due to real-estate values in the neighborhood, says Superintendent Tracy Forck, since property taxes are a main funding source for Illinois schools.

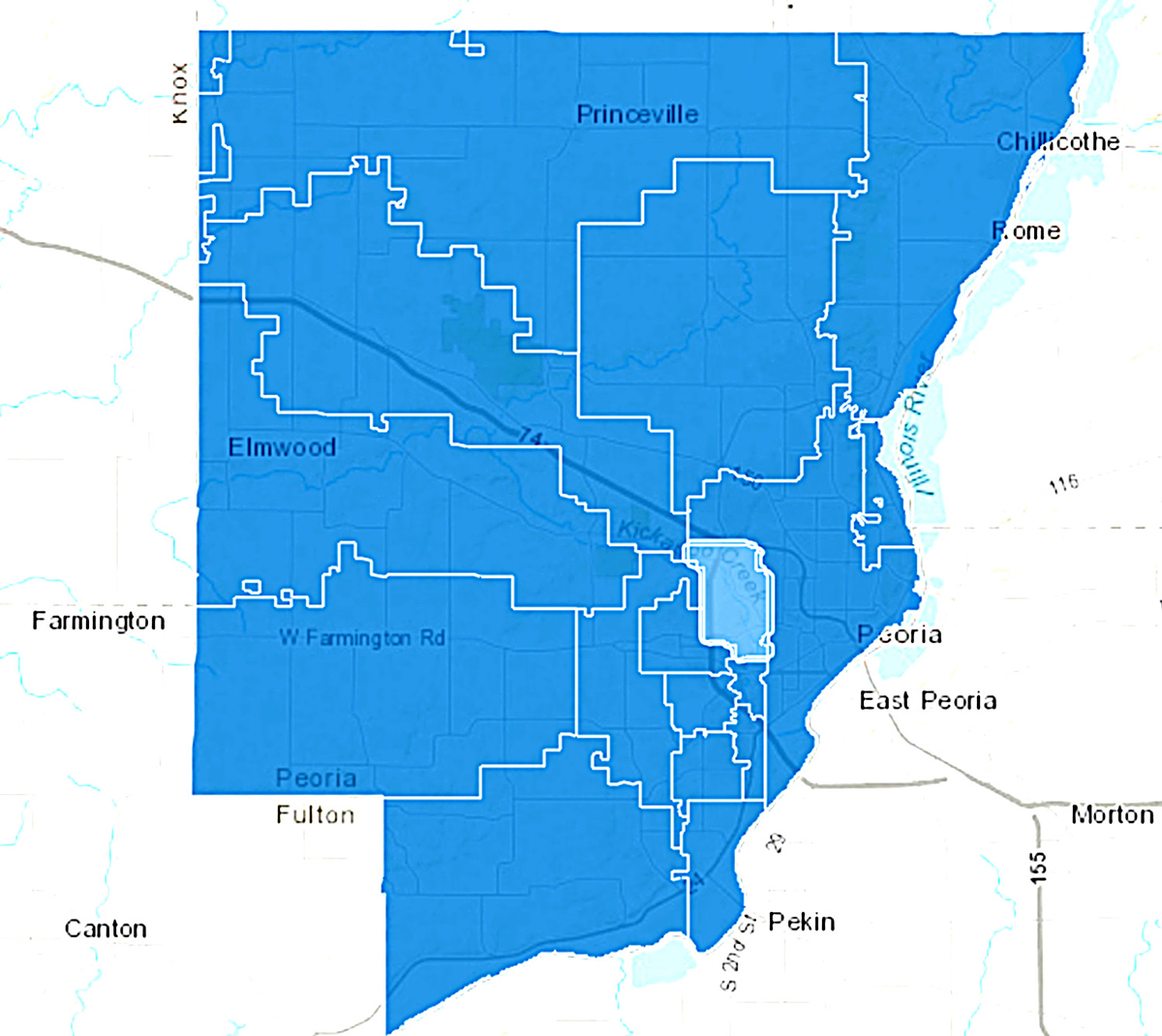

PV Dist. 62 is made up of 440 students in a primary school built in 1949 off Farmington Road, and a middle school built in 2001 on Richwood Boulevard west of Sterling Avenue. An area almost surrounded by Peoria Public Schools/Dist. 150, Pleasant Valley is a “feeder school” to Limestone Dist. 310.

Also, 22 of PV students are registered as homeless, some 5% of the enrollment, a much higher percentage than the City of Peoria, according to the U.S. Dept. of Housing and Urban Development.

“Poverty negatively impacts students in a variety of ways within K–12 education,” says a position statement from the National Association of Secondary School Principals, “factors like health issues stemming from a non-nutritional diet, homelessness, or the inability to receive medical treatment for illnesses.

“These factors often place more stress on a student, which can negatively impact the student’s ability to succeed in a school.”

Second home

Facing such factors, PV tries and sometimes succeeds in dealing with kids’ needs inside and outside classrooms.

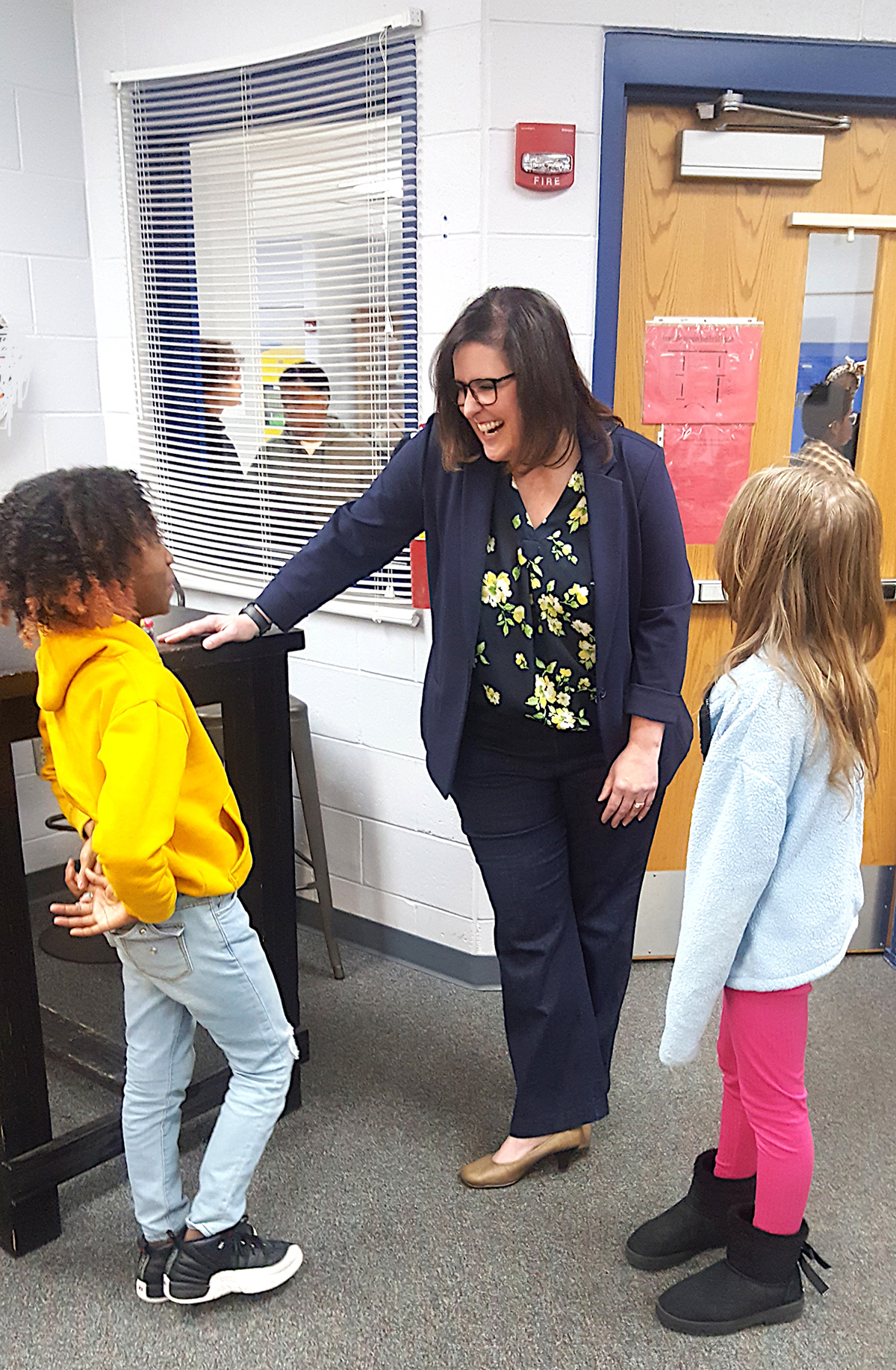

“We try to be a second home for the students,” says Forck, 49, who’s been superintendent for five years. An Ohio native who earned degrees from Bowling Green State University and Illinois State, plus other post-grad work, she previously served as principal at PV’s primary school after teaching reading in the 3rd and 5th grades.

The State of Illinois isn’t unaware of Pleasant Valley’s plight and fight to serve its students, families and community. According to the Illinois State Board of Education, which designates PV’s Primary school as “Commendable” and its Intermediate school as “Targeted,” the district has 46 teachers whose average class size is 18, and learning conditions and student learning criteria comparable with the state overall.

Two areas PV administration wants to address are attendance (both chronic absenteeism and truancy are above 25%) and funding.

“The district has approximately $1 million in local funds and [state] Evidence Based Funding makes up the remaining $3 million,” Forck says. “We are underfunded by $2 million, although EBF has modestly increased each year.

“The district received approximately $4 million in COVID money, which allowed us to install new HVAC systems in both the Primary and Intermediate schools, add a much-needed addition of classrooms at the Primary, and adopt new reading and science curriculums district-wide,” she added.

Pleasant Valley Primary School has been designated ‘Commendable’ by the Illinois Dept. of Education.

PHOTO BY BILL KNIGHT

Outside the box

Forck and the school board “rely more on local analysis” than ISBE’s Illinois Report Card, she says, developing district responses to challenges.

“We try to think outside the box,” she says, noting innovations ranging from protective to practical:

* All students have Chromebooks, and those in 4th-8th have second Chromebooks to use at home,

* 91% of 5th-8th graders take part in the fine arts; 56 students overall are in band using school instruments; and more than 70 are in the Drama Club,

* snack packs and fresh food are distributed to about 200 students monthly,

* a student store offers free clothes and supplies, and

* a laundry room is available to kids.

Often driving the four miles through Pottstown from school to school, can be trying, Forck says, laughing.

“Sometimes I feel like I’m running on a hamster wheel. [But] as superintendent I am ultimately responsible for everything that happens in the district, which is why I am involved in everything from curriculum to behavior.”

“Everything” includes another inconvenience that affects operations: the lack of public transportation to the primary school, contributing to truancy and absenteeism.

“Many of our families do not have transportation, so if their children miss the bus they cannot bring them to school,” she says. “If a child is sick at school they cannot pick him or her up. If there is a need to meet with the teacher, it has to be over the phone. We’re looking at getting a step van to fill that gap. It’s a balancing act. We don’t want to enable more than benefit.”

Good place

There’s no substitute for family, but a feeling of a home away from home has worked out; there are requests to transfer here. “We have a good reputation,” Forck says, also mentioning support from individuals or companies such as the Simantel Group or the Peoria Area Performing Arts School.

“We have families who want their kids to come here, but they have to live in the district,” she continues. “We have no boundary waivers.”

That attraction has helped PV respond to the widespread teacher shortage.

“We have to be aggressive in recruiting,” Forck says. “One time, we had seven special-ed teachers and six left. [But] one of the benefits of being in a district the size of Pleasant Valley is there are not as many layers of bureaucracy that larger districts have, which allows us to be more responsive and flexible.”

Also, Pleasant Valley’s attention to behavior and discipline improved in recent years, another positive to entry-level teachers worried about leading unruly kids or to veteran educators tired of such trouble.

“Our focus this year has been Social Emotional Learning with dedicated time each morning to SEL lessons, and a Google Form check-in each day for students,” Forck says. “This preventative approach has resulted in significantly fewer office referrals and suspensions.”

The check-in asks how kids have slept, how the morning’s going, how they feel about the day, problems with others, and whether they’d like to talk with an adult. In the last five years, office referrals have dropped from 71 to 4 overall, in-school suspensions fell from 22 to 11, and out-of-school suspensions declined from 23 to 2.

Walking through the building, visitors see not just art lining most of the walls, but hear rehearsals, soft laughter in the library and quiet conversations.

A PV staff guide to Protocol, Routines and Support says, “We cannot ‘make’ students learn or behave; we cannot control what happens in students’ home environments; we can create environments to increase the likelihood students learn and behave.”

Forck says, “It’s a progression; gradual steps,” and it’s all enough to make a “Daydream Believer” that PV educators are dealing with challenges.

And teaching.

Recent Comments