In baseball’s infancy after the Civil War, Peoria had 13 teams. This month, as the All-Star Game is played in Seattle on July 11, history can connect the modern sport to feelings for a time when fun trumped money.

A new book, “Ballists, Dead Beats and Muffins: Inside Early Baseball in Illinois” (University of Illinois Press), effectively blends history and nostalgia, sparking an appreciation of the National Pastime.

There are other books about 19th century baseball, but this 250-page gem by Robert D. Sampson is an exhaustive focus on baseball’s early style and sweep when gentlemanly players, civic leaders, and hosts of spectators stressed the bliss more than the score.

Between 1865 and 1870, base ball (as it was then known) had ceremonies and rituals of courtesy, and playfulness was the norm, as virtual parades greeted opposing teams’ arrivals on trains or boats.

In four years it “swept through nearly every village, town or hamlet in Illinois large enough to field a team,” Sampson says. “At Peoria, ballclubs sprouted everywhere.”

Army recruiter Capt. M.A. Stearns in 1866 helped re-organize the Olympic Base Ball Club, which had folded after a season, writing, “No reason exists why Peoria, the second city in the state, should be behind in the establishment of an institution which would result in so much benefit to her young men.”

Curiosity

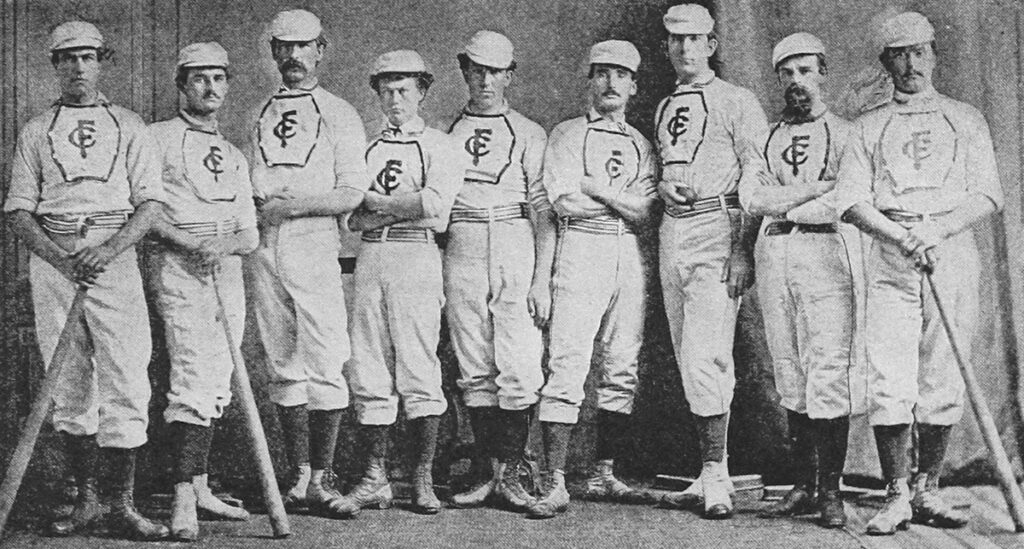

The baker’s-dozen clubs in Peoria were part of a game — an activity and a curiosity — that spread like a prairie fire, numbering hundreds of teams from Rantoul to Galena, topped by the Chicago Excelsior Base Ball Club, the Bloomington Base Ball Club, and Rockford’s Forest City Club (featuring Hall of Famer Albert Goodwill Spalding — future sporting-goods titan and author of 1911’s “Base Ball: America’s National Game.”

Then baseball essentially collapsed, to be reborn in ways more familiar to today’s version.

The American game has been traced to New York’s Greenwich Village in the 1820s, with little to do with Abner Doubleday or Alexander Cartwright. In fact, Brooklyn sportswriter Henry Chadwick had more to do with its development than anyone, compiling rules the sport adopted, developing standards of play for positions, introducing the batting average, and creating what evolved into scorecards.

“The 1860s Illinois game was a cauldron of fun, rituals, moral purpose and civic pride … all recounted in newspaper commentary that boiled and simmered before it turned tepid toward the end of the decade,” Sampson says.

There was plenty to see; the game was almost all offense (double-digit scores weren’t uncommon).

Community support

“Illinois communities of the 1860s were different in many ways,” Sampson tells The Community Word. “For one, they were smaller. Second, while there was some penetration by national commerce (that’s why towns battled for railroads), much business was owned locally. People were in close contact every day and likely knew most of their fellow residents [with] lots of well-attended community events, including concerts, lectures, etc. They turned out not only to watch the “skilled” teams but especially their good-natured friends and neighbors who played in ‘muffin’ games, ones that lampooned the creeping fixation on winning and rules disputes.

(The book title’s derived from what people called players: ballists; muffins were less-talented teams that played for novelty and amusement; “dead beats” refers to some clubs’ offbeat names, such as the Ashley Dead Beats, Rock Island’s Lively Turtles, or Cairo’s Clodhoppers.)

Once, Peoria Enterprise and Excelsior teams merged into the Fort Clark Base Ball Club, and originated commercial sponsorship, with backing from a bakery. Others followed, including Ottawa’s Clifton Club (backed by a hotel) and the Springfield Capital Club (supported by the Capital Horse Railway).

Muffin pans

But the Fort Clarks squad was so weak that before a Fort Clarks-Rock Island game, the Peoria Transcript said it would be shocking “to have our club beat another city’s club. We shall have to break the news gently to our readers.” The club didn’t dramatically improve. In 1870, Ottawa’s Shabbonas defeated the Fort Clarks 59-6, prompting Peoria to “quit the game in disgust and leave the field.”

Future sporting goods giant Albert Spalding is third from the right in this photo of Rockford’s Forest City club. Learn more about the early days of baseball in Illinois in ‘Ballists, Dead Beats and Muffins: Inside Early Baseball in the 1800s.’

Frustrations emerged in other ways. Bloomington banned baseball games within the city limits. Ball playing was also prohibited in the streets of Decatur and Cairo. Complaints were raised about ball playing in public spaces in Jacksonville, Quincy and Peoria (where they practiced in an area between Jefferson and Madison). But no legal action followed.

Other issues ranged from travel and attire to the risk of injuries and the increasing need for players to be skilled. Teams needed access to railroads and riverboats, so Peoria’s Fort Clarks took a train to Chillicothe to play, and a steamboat to Lacon for a game.

In 1866, the Transcript remarked that after shirts worn by the Olympic team split during play, “each clubber looked like a 17-year locust just sprouting,” but the newspaper praised their caps and a local hat maker for “better and cheaper hats than those found in Chicago or New York.”

Throughout, Sampson resurrects players’ names forgotten since, plus some of the prominent business and political figures who helped organize teams: Fred DuBois in Springfield, J.C. McQuigg in Pana, and Hiram Waldo in Rockford.

“The project took about 10 years, most of it spent in research on microfilm,” says Sampson, editor of the Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, a former newspaperman in Eastern Illinois, and author of “John L. Sullivan and His Times.”

“I was able to use Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum microfilm reels at home (after purchasing my own machine),” he continues. “I could work, night and day, going through thousands of pages. I learned early that search engines can pass by important stories, so unless you are turning those pages yourself, you’ll have no idea what is missed. Plus, there is no better way to ‘know’ a historical community than perusing newspaper pages.”

Old timers

Apart from the history and analysis, Sampson’s notes, index and list of 19th century newspapers are terrific, and readers will value him avoiding some pop historians’ “presentism,” the tendency to impose current norms for past facts.

“An often-made mistake among writers of baseball history is looking at the past through the perspective and knowledge of the present,” he says. “We must try to see the world as they saw it and exclude the subsequent history of the game — professional teams, the rise of town teams later in the 19th century, the game’s evolution in rules and equipment.

“Trying to imagine what they saw and felt (based on actual newspaper commentary plus the scattered memoirs of former players), I reached some answers,” he adds. “I found that the game’s arc began with an explosion of interest and embrace of the game followed by decline. Why? As the game became more competitive (communities saw a winning team as a competitive advantage in striving for railroads, economic growth, and bragging rights), the stakes increased. Complicating this was widespread gambling, which caused problems among spectators. In one instance, these tensions led to a postgame free-for-all fight. All these factors put more pressure on umpires and created rules disputes.

“As these controversies and disappointments grew, people tired of reading about rules disputes and how the latest East Coast touring team had dismantled a local favorite.”

By 1870, the gentlemanly type of baseball and its “once-treasured rituals were all but gone,” Sampson writes.

Baseball more than 150 years later can still be fun, of course, whether played on backyard sandlots, in youth leagues, adult softball, or watched in stadiums or on screens. But it’s not the same. Nothing is.

But, oh, there was a time.

1 comment for “America’s Pastime: Illinois base ball in 1800s fun, first”