Last month’s column parsed newspaper reports on this summer’s larger, more intense and deadly weather extremes. Other (omitted last month) headlines concerned growing crop and livestock losses. Georgia lost 90 percent of its peach crop; Florida lost more than 90% of its orange crop, its lowest harvest since 1928; next, extreme heat and flooding decimated India’s tomato crop, resulting in a 400% price hike for a dietary staple; then Kansas’ most intense drought in 128 years reduced wheat yields by about one-third compared to non-drought years; finally, a humid heatwave killed thousands of cattle in Nebraska and Kansas. Additionally, two years earlier, a huge marine heatwave in the North Pacific killed more than a billion sea critters. Temperatures along the shoreline reaching 122F, boiling mussels and clams alive. Fish took a hit, too. Salmon, now too costly for many consumers, will become even more expensive.

Thus far, losses have been local or regional. It may not stay that way. For some time, climate scientists have worried about the possibility of simultaneous crop losses across several cereal gains — corn, rice, wheat — that provide the bulk of world caloric intake. As Kornhuber’s (2023) research indicates, meanders in the jet stream could bring drought and high heat to several of the world’s breadbaskets at the same time. The end result could be substantial reductions in the yield of more than one essential grain. Both prices and hunger, each already on the upswing, would skyrocket and threaten the political stability of countries with food shortages. Remember the Arab Spring, which was precipitated in large measure by soaring food prices?

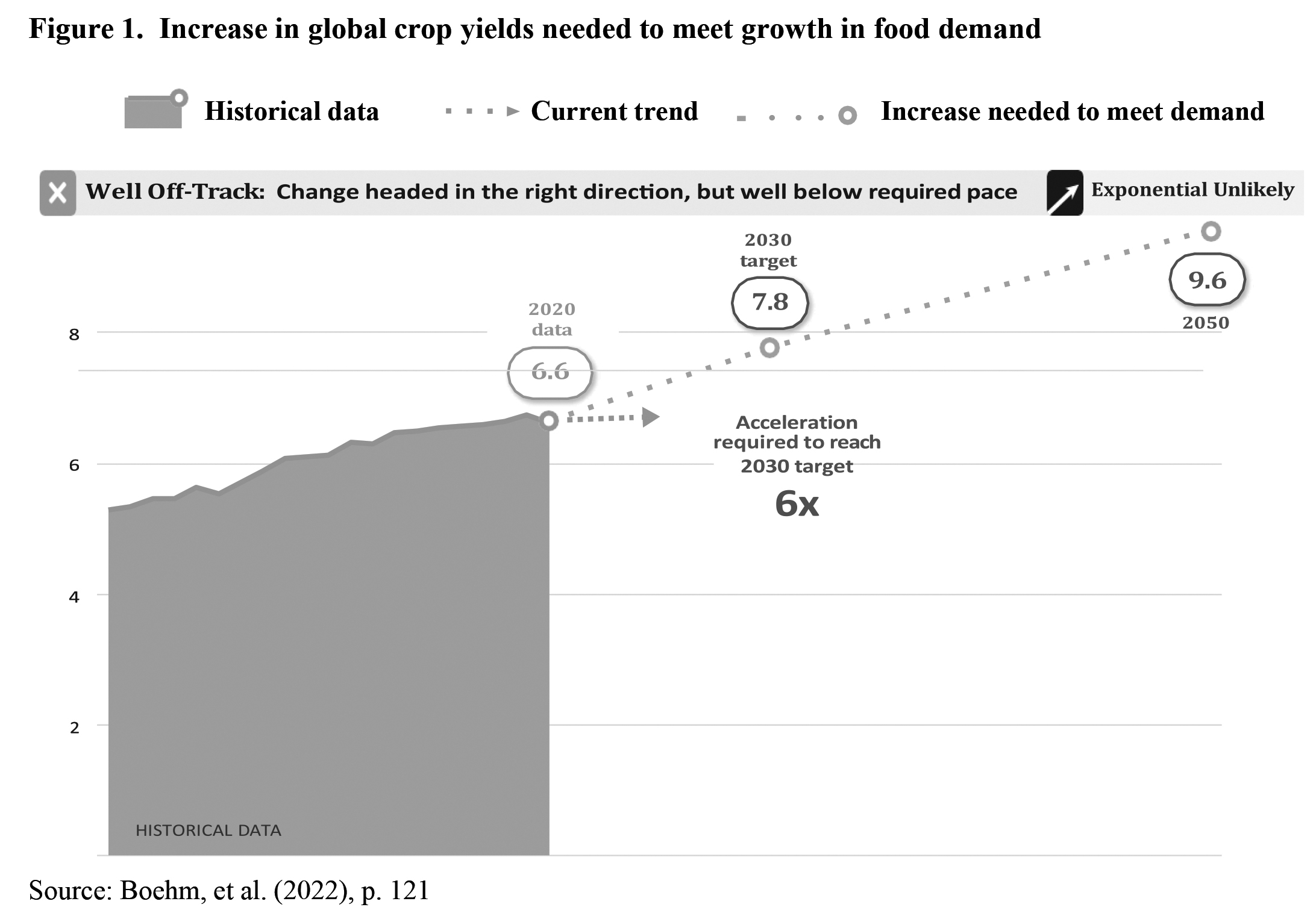

If we set aside this worst-case scenario, things are still dire. Global food demand is projected to increase 45% by 2050. As Figure 1 shows, our current agricultural system will be unable to meet this increase. Moreover, agriculture relies heavily on greenhouse gas-generating practices, which means that food production, processing, and delivery generate about 30% of global carbon emissions (Boehm 2022). Agriculture must reduce its emissions if we are to stabilize the climate, but emissions are still increasing.

While radical yet doable transformations of agriculture will be required to feed people in the future, the quickest and smartest stopgap solution to food insecurity is often overlooked. Until 2008, the U.S. stockpiled food for possible domestic emergencies and for food crises overseas. However, when food prices spiked during the 2008 financial meltdown, the U.S. depleted its entire food stockpile and replaced it with a cash fund to meet emergencies through food purchased in the marketplace.

This daft policy ignores a self-evident truth: We can’t eat money when the cupboard is bare. Chinese and Egyptians understand this and have well-provisioned granaries. China’s stockpile contains

650 million tons of rice and wheat along with large quantities of corn and pork. And Egypt had the foresight to store enough wheat to cover more than five months of consumption — an astute move since Ukrainian and Russian wheat imports, both disrupted at the moment, meet 85% of its needs.

In contrast, our foodless Strategic National Stockpile stores up to 700 million barrels of oil. It is perhaps no surprise that our auto-obsessed country has decided to keep cars running rather than feed hungry citizens should there be shortages of fuel and food.

References

Avi-Yonah, Shera. 2023 (June 23). Florida’s smallest citrus crop in a century to put squeeze on shoppers. Washington Post; https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2023/06/17/florida-oranges-shortage/

Boehm, Sophie L., et al. 2022. State of Climate Action 2022. Bezos Earth Fund, etc.; https://climateactiontracker.org/publications/state-of-climate-action-2022/

Einhorn, Catrin 2021 (Jul 23). Like in ‘Postapocalyptic Movies’: Heat Wave Killed Marine Wildlife en Masse. New York Times; https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/09/climate/marine-heat-wave.html9

Hamilton, Tucker. 2022 (Feb. 25). Food Insecurity: Why the US Needs a Strategic Food Reserve; American Security Project; https://www.americansecurityproject.org/food-insecurity-why-the-u-s-needs-a-strategic-food-reserve/

Kornhuber, Kai. 2023 (July 5) Guest post: Climate models underestimate food security risk from ‘compound’ extreme weather. Carbon Brief; https://www.carbonbrief.org/guest-post-climate-models-underestimate-food-security-risk-from-compound-extreme-weather/

Siripurapu, Anshu & Noah Berman. 2023 (March 2). The State of U.S. Strategic Stockpiles. Council on foreign Relations; https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/state-us-strategic-stockpiles

Smith, Mitchell. 2023 (Aug 9).

First Scorched, Then Soaked: Weather Whiplash Confounds Farmers. New York; https://www.nytimes.com/2023/08/09/us/kansas-wheat-harvest-drought.html?searchResultPosition=1

Recent Comments