Time can offer perspective and appreciation to events undertaken in youth, when courage and cowardice collide.

This spring’s widespread campus protests, focused on Gaza, have rekindled meaningful memories. There were workshops I used to do for junior high schoolers on the First Amendment when I was a university journalism professor. “GRASP it,” I’d say, using a mnemonic device indicating the five rights: Grievance, Religion, Assembly, Speech and the Press.

Gaza protests exercise all these First Amendment rights.

There’s also the recollection of personal involvement in similar demonstrations 50-plus years ago, when protests erupted around war, student power, racism and disappointing politicians. I’m certainly nothing special; such actions, then as now, were less rites of passage than rites of passion with millions of us engaged. I hope today’s protests are similarly felt, with neither pride nor panic.

Echoing in young people’s stereos, radios and mind was music like Buffalo Springfield’s 1966 “For What It’s Worth,” with its line “There’s something happening here …”

I was a college freshman when the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated and, two months later, Robert F. Kennedy was gunned down, followed two months afterward by the Chicago police riot at the 1968 Democratic Convention, where peace candidate Sen. Eugene McCarthy lost the nomination to LBJ VP Hubert Humphrey.

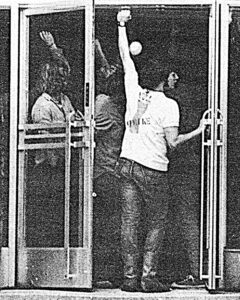

A young Bill Knight in a ‘strike’ shirt at the occupation of the building housing ROTC at Western Illinois University.

Shock and outrage swept society, including campuses, where students resented what seemed like arbitrary authority that mirrored heavy-handed government, and by February 1969, increasingly angry students defied a disputed student government election at Western Illinois University, and 2,000 of us took over the union building here.

Nine months later, hundreds marched throughout Macomb, part of the national Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam; weeks later, dozens of buses from Illinois traveled to Washington, D.C., to participate in the November Moratorium, where some 500,000 Americans gathered around the Washington Monument to oppose that war.

In contrast to such turbulence, days later the Pentagon held a draft lottery that randomly pulled birthdays to see which young men would go to war. In my dorm, men gathered to watch their destinies picked on live TV. My number was 204, and the highest number sent to Vietnam was 195. A friend on our floor was numbered 137 and he enlisted soon after. He’d die in Vietnam the next fall.

Of course, Vietnam already was on the minds of people whose student deferments had exempted them from the military draft. A schoolmate’s brother had returned from Southeast Asia gravely wounded. An older neighbor who’d played wiffle ball with us just a few years earlier was killed in combat that summer.

Activism bubbled for months and boiled over after National Guard troops shot anti-war protestors at Kent State, killing four and wounding eight. Two weeks later police opened fire at student protestors at Jackson State, killing two and injuring 12. Almost spontaneously, students invaded WIU’s ROTC building and occupied it for days, when students went on strike.

Seeing recent “tent cities” disrupting and criticizing colleges and political leaders from President Biden to Israel’s Prime Minister Netanyahu also is reminiscent of disillusionment felt in the ’60s and ’70s. There really was political corruption then, too.

President Nixon was forced to resign after conservative Republicans joined with liberal Democrats to hold him accountable for much of the Watergate scandal. One of Nixon’s aides, John Ehrlichman, was one of those convicted, and he served 18 months in prison.

In the ’90s, Erlichman, in an interview with Harper’s magazine journalist Dan Baum, conceded how one of many Nixon administration initiatives targeted people like me and my friends.

“The Nixon campaign in 1968, and the Nixon White House after that, had two enemies,” Erlichman said, “— the anti-war Left and Black people. You understand what I’m saying? We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or Black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and Blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities.

“We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news,” he added in Baum’s 2016 cover story on the War on Drugs. “Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.”

Besides the reassurance many of us felt that our uncertainty or naivete were less folly and vanity than clumsy but correct, there have been moments of profound reconciliation, between those who opposed the Vietnam War no matter what, and those who backed it. Veterans were divided, too, and one vet I argued with often was a colorful guy who resembled the grizzled cowboy actor Leo Gordon. We developed a mutual respect, agreeing to disagree, and we both became newspapermen, then good friends. Likewise, hometown Vietnam vets returned, harboring little ill will toward anti-war classmates.

WIU’s ROTC program eventually was moved from the building students temporarily seized, and about 20 years after that occupation I taught there.

I hope this year’s student activists make a difference, endure difficulties, and find common ground with their current antagonists.

As the Chambers Brothers sang in 1967, “Time Has Come Today.”

Recent Comments