Meteorologist Chuck Collins sits at a bank of computers at News25’s weather center in East Peoria.

BILL KNIGHT

Twenty years ago, Illinois State Climatologist Trent Ford was a Roanoke teen at home midday on July 13 when he heard a weather alert about a “super cell” moving through the area.

“I’d just gotten back, so I rode my bike to get my sister at the swimming pool — where it was still sunny, so people were still swimming,” he told The Community Word. “By the time we got back home, you could see the rotation in the sky, so we went downstairs and I got her and our pets settled, and I went out to look — which you’re not supposed to do — and watched it roll in.”

Before the tornado passed, it caused an unknown amount of damage, the National Weather Service reports, but it destroyed the 250,000 square-foot Parsons Manufacturing plant, where about 140 workers sheltered in concrete-reinforced bathrooms. Steel beams and metal siding from Parsons were blown almost a mile east, There were three injuries total, NWS says, none at Parsons.

“At the time, I didn’t appreciate what had happened,” Ford added. “Now, in the (weather) community, that tornado is still one of the most talked-about in the state.”

Hours after Ford reflected on Roanoke, Illinois sustained dozens of tornado “pathways” and 20 confirmed twisters, according to the NWS — already making 2024 the second busiest year for tornadoes, after 2011.

Dropping from thunderstorms, tornadoes are rotating funnel clouds of dust and material swept up by violent winds. They’re gauged from EF0 to EF5 in severity.

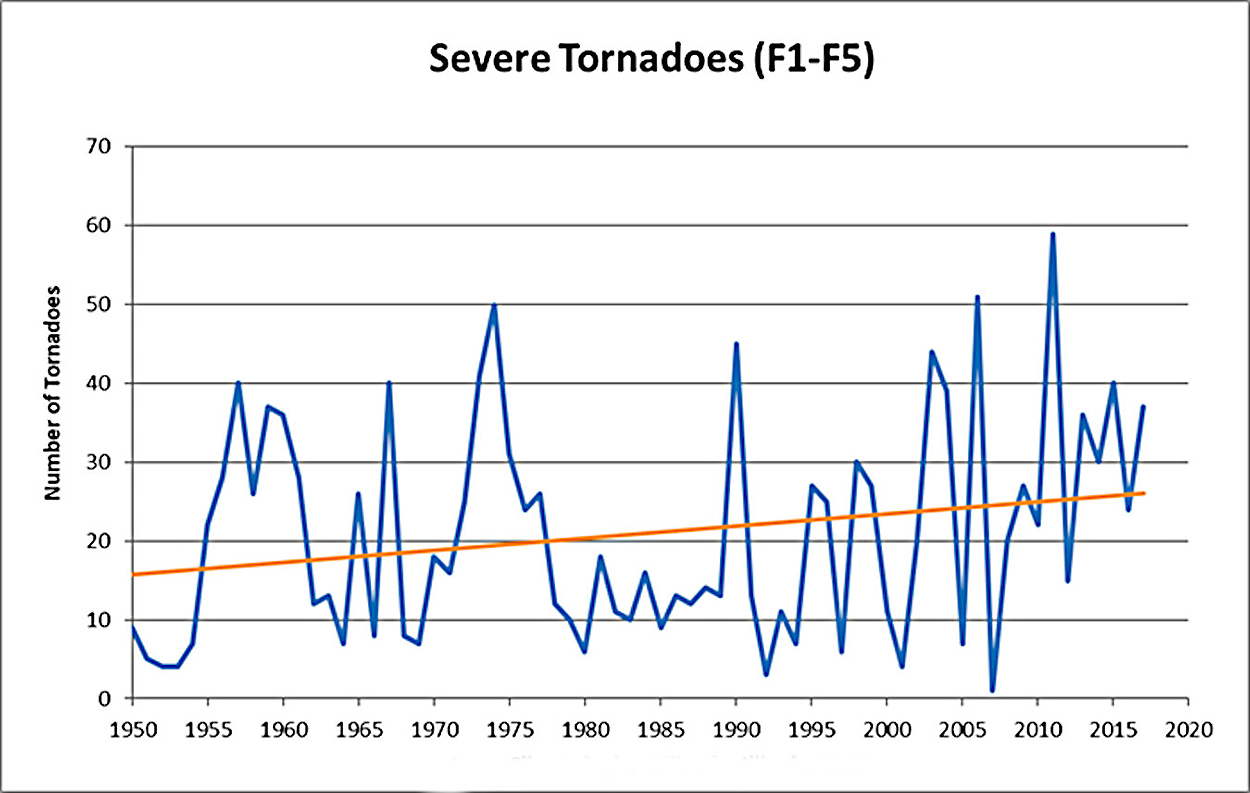

Last year, Illinois had more than 125 tornado reports, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, leading the country in 2023. Since 1950, the number of severe tornadoes has steadily risen, too.

- In the decades since 1950, tornadoes have caused thousands of injuries and hundreds of deaths in Illinois, according to data from the University of Illinois’ Department of Atmospheric Science.

- The most frequent months for tornadoes in Illinois are April-June, but they’ve happened every month.

- Tornadoes happen most often between 11 a.m. and 11 p.m.

- The total number of tornadoes in Illinois are up since 1950, and the most severe tornadoes vary from year to year, but has a rising trend line (See chart).

Tri-County alley

The Tri-County area has had three memorable tornadoes. The NWS says Woodford County has had 47 tornadoes since 1950, including the EF4 tornado at Roanoke, where winds were clocked at more than 200 mph as it remained on the ground for 10 miles.

Tazewell County has had 66 tornadoes in seven decades, but though the EF4 tornado that hit Washington in November 2013 was catastrophic, it was part of one of Illinois’ largest November outbreaks ever — 25 in one day. Three fatalities, 121 injuries and more than $900 million in damages resulted from winds in excess of 190 mph, and its 46-mile path continued through LaSalle and Livingston Counties.

And in Peoria County, which has had 28 tornadoes since 1950, the EF2 tornado that hit Elmwood about 7 p.m., June 5, 2010, damaged most of the town square, destroying 30 businesses, 10 homes and dozens of vehicles, with an estimated $85 million loss but no injuries.

Northern Illinois University meteorology professor Victor Gensini said 70 years’ of data indicate a shift eastward from the area long known as “Tornado Alley” — Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas and Nebraska — to Alabama, Mississippi, Tennessee, Indiana and Illinois.

Meteorologist Chuck Collins at News25 in central Illinois thinks of increasing tornado activity as a reflection of another shift — “It’s about shifting seasons,” he said.

As remnants of Hurricane Beryl brought showers through the Midwest (and the premiere of the film “Twisters” a week ahead), Collins relaxed at the station’s weather center and said, “I ask Baby Boomers about weather changes they notice. Winters are mild now. We’ve only had two white Christmases in recent memory.”

Thirty years ago, Illinois used to have an average of 27 tornadoes a year, he said, and now it’s 58 — an effect of the changing climate, he said.

Asked whether he gets pushback to climate-change connections, Collins said, “I talk to a lot of groups, and there’s not any, not like back when Al Gore was talking [in the early 2000s, when his Oscar-winning documentary “An Inconvenient Truth” was released]. Then, there was some ‘Does it or doesn’t it exist?’ questions. Now most people say climate change isn’t fantasy; it’s reality.”

Twister tech

Technology is another factor in increased numbers since tornadoes are almost invisible until dirt and debris show the funnel.

“Before Doppler radar, radar might not pick up weaker tornadoes, and might pick up other things — flocks of birds or aircraft,” said Collins who’s worked in weather for almost 38 years, 23 years at WMBD-TV 31 and 14 at WEEK-TV 25.

“Doppler is so much more sophisticated,” he continued. “Instead of relying on visual sightings, we use Doppler to dissect and filter what’s out there — in 3D — and show wind velocity, energy signatures, even debris in the air.”

Information from NWS’ Lincoln office and satellite imagery are much better than relying on Emergency Management Agency spotters or storm chasers to see a tornado and start local sirens.

Satellite images are delivered for broadcast by TV stations’ outside vendors, but Collins and crew issue warnings, too.

“We might see a nasty-looking cell and tell people to seek shelter before the Weather Service,” he said.

Meteorologists are vulnerable, too, like the November 2013 on-air broadcast of News25 staff instructed to go to their safe place. “We were warning viewers about the Washington tornado,” he said. “Then it was across the street from the station. We heard it. We took shelter.”

Take cover

These days, tornado preparedness rarely includes tornado myths, like going to the southwest corner of a basement or opening windows.

“People are generally more cautious now,” Collins said, but as recently as 2011, when Joplin, Mo., was hit by an EF5 tornado that killed 156 people, an early warning didn’t help everyone.

“A National Weather Service survey found a vast majority of those killed did not take immediate action when warnings were issued,” Collins said. “Residents had 20 minutes lead time, but many wanted verification including visual confirmation.”

Preparing means thinking ahead, making plans and bracing buildings. The safest spot in a building is in a small, reinforced room or closet on the lowest floor near the center of the structure.

“The Weather Service can certify a designated location as ‘storm ready’,” Collins said.

Besides mobile-home residents being advised to plan for retreating to a sturdy building, structures with many people are vulnerable, too, from big-box stores and dorms to hospitals and industrial buildings.

The Parsons episode was instructive. “At the time of the Roanoke tornado, I went to my girlfriend’s house and everyone was OK, but the tornado threw a truck right through a shed,” Ford remembered. Now, he sees the wisdom of preparation.

“Parsons is a great example of how to design buildings to save lives,” he said, “not only was there shelter. Everybody knew what they were supposed to do and where to go.”

Recent Comments