Diversity training helps expand understanding.

Journalism is foundational to democracy, but the craft is still evolving based on our levels of assessment and training in issues related to diversity.

It used to seem OK to repeat a police description of a suspect as “a 6-foot tall African American man in his 20s.” It doesn’t seem OK to me anymore after taking a course about 15 years ago on diversity at the Poynter Institute for Media Studies, a journalism think tank.

The instructor at Poynter explained including “African American” in the description was discriminatory. No, several of us insisted. We don’t discriminate. This is how police release information to assist in searching for a suspect. “African American” is part of a visual clue provided by police.

The instructor persisted. Rather than helping identify a suspect, it makes all tall African American men potentially the alleged criminal. It’s profiling.

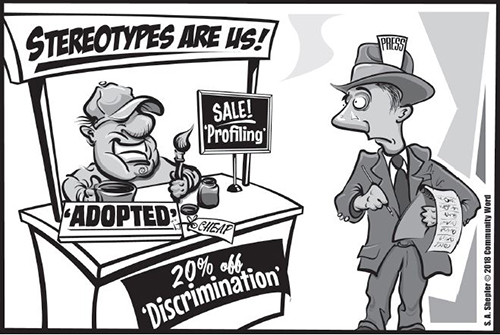

It was a difficult discussion and a difficult period of self-examination. Many of us left that seminar feeling we had been practicing journalism in a way that furthered discrimination and stereotyping.

The same type of ethical question confronted me recently in Peoria.

Susan Berry Brill de Ramirez was a wonderful person I had the opportunity to interview last year. She was a professor at Bradley University, and she was a volunteer Internet tutor teaching Baha’i students living in Iran. That volunteer work came with personal risk. The Baha’i are discriminated against, incarcerated and killed in Iran because they believe in education, the equality of women, universal humanity and equal rights. She understood her work meant she could never again safely land at the airport in Tehran without risk of being arrested.

“I would be more worried if I lived in London, but there is a certain amount of safety that comes with living in Peoria,” she said.

She and her husband were murdered at their home in Princeville in October, allegedly by her son and another man.

Sheriff Brian Asbell was prompt and as transparent as possible with his press releases and press conferences about the investigation and ultimate arrest.

We all wondered how could this happen? How does a son kill his mother and his father? Then reporters added a detail. He was adopted.

Many people reacted with “Oh, that’s how it could happen. He’s adopted.”

But being adopted has nothing to do with being a murderer. A person who is adopted is no more likely to murder than someone who is overweight, blonde haired or tall.

“Adopted” is a personal detail, and in journalism we understand personal details make news more interesting, but that’s one detail that maybe should have been held, at least initially. Was it relevant? Maybe it would ultimately come out during a court hearing. Maybe some newsrooms justified using the information because it had already been reported by other media outlets and was therefore in the public domain.

But do those explanations meet the standard of foundational journalism? Using “adopted” so early in reporting conveys a message –– a negative impression that adopted children are more prone to violence than biological children.

The murder of de Ramirez and her husband triggered difficult assessments of how inadequately our society deals with mental health issues. Their son apparently was grappling with mental health issues for years. His parents were highly educated, compassionate, well-connected people yet they couldn’t access adequate professional help their son needed.

Rather than sinking more billions into jails and prisons, we need to seriously start investing more money toward mental health programs and stop conflating “adoption” and “African American” with a proclivity for criminality.

Food as a value

Local, sustainable, organic family farms. Community Word has written about heirloom organic wheat grown at Janie’s Farm Organics in Danforth about 100 miles east of Peoria. Recently, Naturally Yours in Peoria’s Metro Centre started selling freshly milled flour from The Mill at Janie’s Farm.

Recent Comments