PAUL KRAINAK

The artists I’ve previously written about who were instrumental in the neighborhood’s consequence include Michiko Itatani, Dennis Kowalski, Phyllis Bramson, Dan Ramirez, Lindsay Lochman & Barbara Ciurej, John Phillips, and Gary Justis. I have upcoming columns on Buzz Spector, Frances Whitehead, Jean Sousa, Jeff Abel and others. These artists were instrumental in building an identity, for the city that ran parallel to Chicago’s establishment. With the first artworld decentralization looming in the ’70s and ’80s, Chicago became a critical visual culture laboratory contributing to a national dialogue on contemporary art.

These emerging artists eagerly asserted that the context and content for their work was their responsibility. They became organizers, curators, critics, grant writers, administrators, performers, editors, carpenters and janitors. Part of their success was their distance from New York even though it was generally thought of as a liability. A certain critical autonomy and confidence was possible because they built an infrastructure not indebted to decades of East Coast license and cultural supremacy. They didn’t wait to be anointed by Chicago’s museums which were also considered predictably coastal, exclusive and frankly timid.

There were scores of artists who made the alternative spaces viable and productive, significant ones that have always balanced two or more facets of the art industry and some that have taken less conventional visual culture tracks that deserve to be cited. Few of these artists share a similar aesthetic other than maybe a respect for skilled labor and the embedded memory and gratification about the collaborative action of that time. Each has had periods of achievement that circumvented the rise and fall of art market trends and now the threat of pandemic quarantine.

Guy Whitney, “Wounded Spirit Body,” 2019. Watercolor and colored pencil on paper. (IMAGE SUPPLIED BY ARTIST)

Steve Luecking, an accomplished sculptor and digital artist writes fluently on contemporary art with an enthusiasm that comes from 40 years of critical reflection on semiotics, technology and abstraction.

Othello Anderson, an early member of N.A.M.E. has produced radically divergent works that explore themes as varied as landscape painting, drawing, and photography, and delved into subjects like astronomy and mysticism –– the latter in collaboration with former Artemisia member Fern Schaffer.

Larry Lundy, “Looking East of E-Town, 10.28.18” C-print

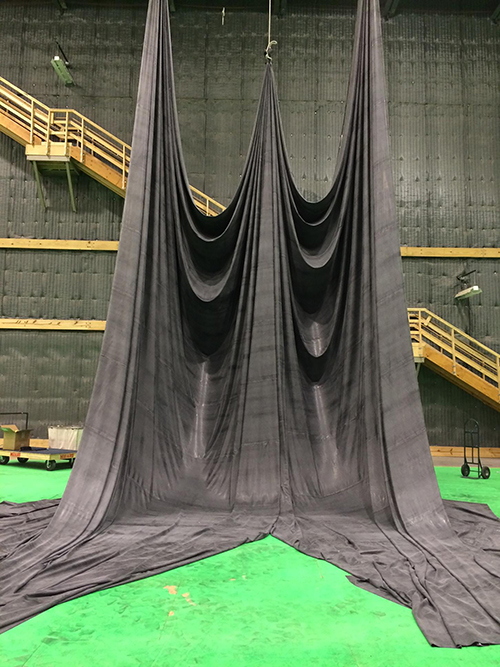

Joel Klaff, Batwing Shroud from “Batman Vs. Superman” 2016

These independent artists are just a few who rate more attention and patronage. They’re seasoned. They didn’t fit the faux-heroism or glamor of late modernism nor today’s globalist turn. They never aspired to simulate coastal aesthetics. Their work may not be legible as deconstructive, relational, or transnational. It’s not ideologically distinguished, but neither is it careerist or nihilistic.

They reflect the principle that an artist’s first audience is other artists. They’re connected by place and, they’re soberly idealistic. Their art hasn’t been interrupted by the COVID-19 alarm while so many of us are flying on instruments. The precarious new norm elbowed trends and theory aside making the future appear barren. The past, on the other hand, looks fertile and redeemable. Is it lucidity or nostalgia? Maybe it’s both.

1 comment for “Inland Art | Chicago’s Hubbard Street district”

Recent Comments

thanks Paul, for describing so eloquently about why I felt at home in Chicago. . . and what also prompted me to curate and produce the LOOP Show in 1981at the landmark Fisher Bldg. It’s my kind of town!