Photo by Clare Howard Organic farmer Henry Brockman points across his field to a path cut through a hillside once forested with oaks. The Enbridge Flanagan South pipeline transects his land and became operational months ago with none of the organized protests surrounding Keystone XL.

While debate over Keystone XL engulfs Congress and the White House, farmers in the Congerville-Goodfield area find themselves sitting atop a river of Canadian Crude Tar Sands oil that eclipses the volume projected for the controversial proposed pipeline to the west.

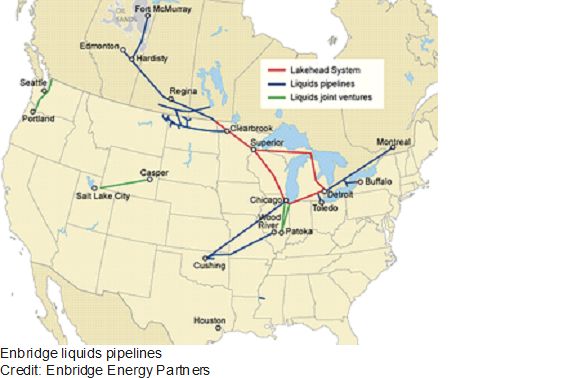

Keystone XL is still hotly debated and years from operational, but the Enbridge line now connects Western Canadian tar sands by pipeline through Superior, Wis., Flanagan, Ill., Woodford and Tazewell counties, Cushing, Okla., and finally Houston/Freeport, Texas, and the Gulf Coast. The line passes El Paso, Goodfield, South Pekin and Havana.

The line through central Illinois was developed “under the national radar” according to an article in Pipeline & Gas Journal. The article cited “generally strong community support along the pipeline.”

Organic farmer Henry Brockman just shakes his head at that characterization.

The earliest visits to the Brockman farm by company representatives in 2012 were to discuss pipeline upgrades. These visits seemed almost routine. The existing pipeline was constructed nearly 60 years ago, and new work would be to enlarge and increase volume.

Brockman recalls company representatives explaining the new pipeline would be larger than the old line and used for natural gas. His topsoil would be carefully preserved and replaced, he was told.

“It is amazing what can be done without the knowledge of the community,” he said recently after learning the pipeline under his land is not transporting natural gas but thick Canadian tar sands oil diluted with a lighter hydrocarbon so it can flow under high pressure.

The upgraded pipeline went online in 2014.

The segment crossing Brockman’s fertile Woodford County farm is part of the Enbridge Flanagan South Pipeline a 600-mile, 36-inch wide pipeline linking Flanagan, Ill., with Cushing Okla.

Photo by Clare Howard The Goodfield Station is one of seven above-ground pump stations on the 600-mile Enbridge Flanagan South Pipeline that connects Canadian crude oil from tar sands in Alberta with the Gulf Coast. The pipeline became operational in November, and at peak capacity it will transport more crude oil than the controversial Keystone XL. Enbridge used Russian-based steel producer EVRAZ for all pipe for the $2.8 billion Flanagan line. Nearly 3,000 people were employed for almost one year during construction of the line but few new permanent positions were created.

While TransCanada Corp. has fielded strong opposition to the proposed Keystone XL pipeline, Enbridge worked on segments of a line connecting Alberta, Canada, to Freeport, Texas, and the Gulf Coast with little fanfare. At capacity, TransCanada expects Keystone XL will transport 830,000 barrels per day. The Enbridge line that cuts through Central Illinois is projected to transport 880,000 barrels a day.

“I won’t say this is bait-and-switch, but Enbridge took advantage of an existing line and national attention diverted to Keystone,” said Joyce Blumenshine, spokeswoman with Heart of Illinois Group of the Sierra Club.

She said the national Sierra Club sued the Army Corps of Engineers over the Enbridge pipeline because the Corps approved segments of the line without adequate evaluation of the totality of the pipeline.

Doug Hayes, Sierra attorney, issued this statement:

“Sierra Club filed a lawsuit over the Flanagan South Pipeline Project – a nearly 600-mile, 36-inch diameter interstate crude oil pipeline that originates in Pontiac, Ill., and terminates in Cushing, Okla., crossing Illinois, Missouri, Kansas and Oklahoma. Despite the approval by numerous federal agencies, there was never any environmental review or public notice before the pipeline was permitted and constructed. The pipeline is now largely complete, but if successful, the Sierra Club’s appeal in the D.C. Circuit could halt pipeline operations and force an environmental review of the entire project.”

Enbridge spokeswoman Lara Beurhenn said all regulatory approval was secured through state and federal agencies. The Flanagan South line was always designed for crude oil from Western Canada and the Bakken region of North Dakota, she said.

The line went into operation three months ago in November and everything is working according to plan, Beurhenn said.

The segment over Brockman’s land is initially expected to handle 585,000 barrels a day.

Brockman said the crew working on the project across his property included only one local person with the rest of the crew coming from out of state. Enbridge’s web site indicated that after the construction phase of the pipeline that employed nearly 3,000 workers, few new permanent jobs would be created.

There are seven pump stations along the route. One is south-west of the Brockman farm outside of Goodfield. These pump stations are the only locations along the route that are above ground.

Brockman said his topsoil was scraped off and preserved while the pipeline was installed and then filled back in over the land. He put an initial cover crop of rye on the land to try to protect it from further erosion. Several heavy rains during the process resulted in significant topsoil loss.

“The soil has lost a lot of fertility,” he said. “You can’t remove it, run over it with heavy equipment, put it back and expect there to be much life left in it.”

Now that the pipeline is operational and the muddy construction sites are integrated back into row crops and other vegetation, Brockman said, “it is amazing this whole thing was done without much knowledge by local communities.”

He pointed out the irony of fighting Keystone XL because of the environmental damage caused by burning dirty Canadian tar sands oil while the Enbridge pipeline has already become a reality with little public opposition.

Maybe Enbridge can be recruited to help environmentalists fight Keystone, he said in frustration.

1 comment for “UNDER THE RADAR: Tar Sands Oil Pipeline Here; Central Illinois Volume Greater Than Keystone XL”

Recent Comments

Re/ “Under The Radar…” Interesting article by Clare Howard in the February CW.

America has the creativity and know-how to be a world leader in producing clean energy and taking better care of our world, and yet here we are stuck in “drill baby drill” mentality.

The plutocrats are steering energy policy in a totally wrong direction based, not on realities of atmospheric quality, integrity of the northern boreal forest, potential for ecological disasters along the pipeline, or clean energy alternatives… but solely on wealth that enriches a few. This peculiar type of ‘socialism’ privatizes profits for a very small group… while socializing the substantial ecological risks and environmental costs which are borne by the rest of us.

Our children and grandchildren should not have to look forward to a petrified 19th century fossil based economy. The shenanigans involved in this filthy tar sands oil business should finally convince our leaders…there is an urgent need to act NOW. We must face the catastrophic potentials of global warming and create a clean and vibrant future… before it’s too late.