BY CLARE HOWARD

Released after almost half a century in prison on a vacated conviction, Cleve Heidelberg waited in the shade of a tree near the parking lot at a free specialty health clinic on Peoria’s south side on a recent Sunday. It was 90 degrees and humid, but Heidelberg was upbeat about his first appointment for medical care outside prison.

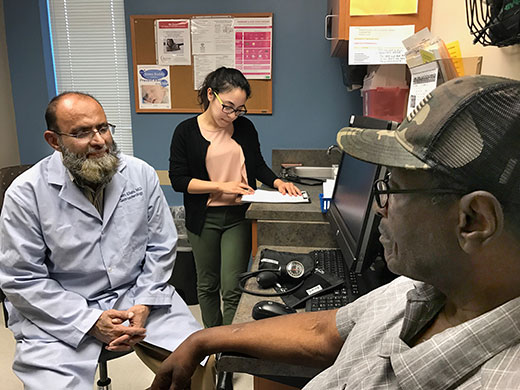

PHOTO BY CLARE HOWARD

Cleve Heidelberg, released from prison after 47 years when a judge vacated his conviction, sees a doctor and third-year medical student for a complete physical and series of tests. Heidelberg said he has so many medical problems he was concerned no physician would see him.

He and his friend Alstory Simon arrived an hour early for a 1 p.m. appointment.

Both men had been imprisoned in Illinois and both were released after judges reheard their cases.

Heidelberg, 74, and Simon, 68, looked like two genial grandfathers spending time together on a Sunday afternoon, but their voices rose and became more strident as they discussed the health care they had received in prison.

“Health care in prison is nonexistent,” said Heidelberg who has trouble getting up from a chair or rising from bed in the morning due to arthritis, congestive heart failure and other conditions. He has been physically disabled since sustaining a severe police beating in 1970.

He said when he saw a doctor in prison about back pain, he received “an aspirin and ‘a slow walker pass’ so I didn’t have to keep up with the mass movement” of inmates from location to location within prison.

“They treat the symptoms in prison not the condition,” he said.

Heidelberg has cataracts and chronic back pain.

He said that inmates in Illinois are required to pay a $5 co-pay to see a doctor.

According to the not-for-profit Prison Policy Initiative, that amounts to 55.5 hours of work at the minimum prison wage of 9-cents per hour. That would be an equivalent co-pay of $458.33 for someone on the outside earning the minimum wage.

Heidelberg said he did not work in prison because of his disability.

Simon, who was in prison for 16 years before a judge ordered his release, said, “There are more inmates than jobs in prison.”

He did not have a prison job for years but then started cooking for the prison staff.

He said that $5 co-pay means inmates have less money available to purchase personal care products like toothpaste, soap, shampoo and deodorant. Inmates who smell and are unkempt can be given a citation, he said.

Heidelberg and Simon laughed disparagingly over the toilet paper situation in prison.

“Inmates are given one roll a week,” Simon said.

Heidelberg said, “Newsprint becomes highly valued.”

Simon said, “What tickles me, what I have never understood, is how do you stay clean without soap and cleaning supplies. If you smell, you can be written up for a hygiene violation.”

He said in some maximum-security prisons, inmates have access to a shower infrequently.

“If the prison goes on lockdown, that means no showers. Lockdown for four to five months means no showers four to five months,” he said, explaining a system he devised filling a plastic tub with warm water, standing in it and giving himself a sponge bath.

Both men had been at Hill Correctional Center in Galesburg for years, and while there, they both had access to showers daily.

Heidelberg’s main source of income while in prison was spending money his older sister sent him for 47 years. Simon operated his own home improvement business before he went to prison so he had money in an account to pay for expenses while he was incarcerated.

“I had cell mates, so out of necessity I had to buy them soap, deodorant and toothpaste so I didn’t have to smell them,” he said. “Indigent prisoners are supposed to get basic supplies, but I ended up paying for my cell mates.”

Air conditioning is rare and prisoners depend on fans in the summer, they said.

Both men complained about dental care in prison.

“I went in with perfect teeth. I received no cleaning, no care, only extractions,” Simon said. “I got pyorrhea and my teeth became loose and started falling out. Then all were taken out and I have full dentures.”

A spokesperson with the Illinois Department of Corrections declined to comment on the specific charges made by Heidelberg and Simon. She referred Community Word to a department policy regulation posted online.

Wendy Sawyer, a policy analyst with the not-for-profit Prison Policy Initiative, said a co-pay of $2 to $5 “looks relatively small to people on the outside, but for people inside who make no money . . . the co-pay deters care.”

She said prison healthcare is typically geared toward symptoms and short-term fixes, not looking at the bigger picture.

Among incarcerated people, 50 percent who want to work are unemployed, she said.

Illinois does have a policy for providing care for indigent inmates, but Sawyer said it is virtually impossible for independent researchers to assess whether a policy is enforced or abused without full transparency and communication.

When people in prison go without basic healthcare, Sawyer said, that’s a violation of basic human rights.

In 2013, the United Nations adopted the “Standard Minimum Rules for Treatment of Prisoners.” However, when there is no transparency, it’s impossible to evaluate the treatment of prisoners other than to rely on their own first-hand accounts.

Recent Comments