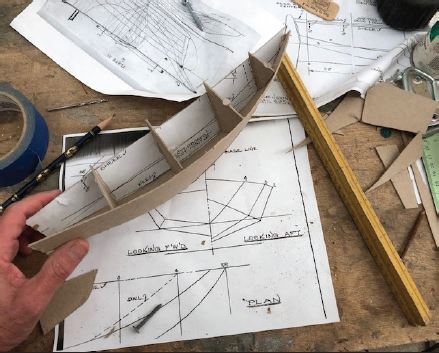

“Catboat Model” (Photo by Bob Emser)

Bob Emser’s body of public works are at ease in prescribed settings like urban plazas and sculpture gardens. The contours of his work are clear, adaptive and organic. He’s situated his sculpture on concrete and on soil, riffed on constructivist geometry and Prairie School detail and blended technologies of sea vessels and aircraft, all intermittently taking center stage. A repetitive buoyancy and material sophistication distinguishes his practice. Like an engineer, he doesn’t fetishize construction to the detriment of an object’s elemental form. The object is also the sign. He designs work that celebrates the tactical and strategic positioning of public works, taking pains to produce sculpture that calls attention to the space between nature and culture. His wing and foil forms unfolded liberally, appealing to air, water and earth, acknowledging all of the pleasurable capacities of motion.

Bob likes to question the culturally assigned status of art forms in relation to the lesser designated, but equally complicated, history of ordinary objects, particularly when both are inventive and have been perceived as beautiful over time. Essentially he asks what it is that strikes us as worthy of our attention.

“Test Flight,” a sculptural installation just a few years ago at Two North Riverside Plaza in Chicago, shifted his attention from traditional sculpture and its relationship to place, to more ephemeral notions about artistic play and labor. For the first time, Emser displayed objects that expressed his boyhood fascination with constructing toy models.

Emser’s newest turn extols the utilitarian design elements in romantic objects like planes and now boats. He’s attempting to steady the incongruities and ambiguities of aesthetics by making actual replicas, which simulate art but still float on an inland sea. The project employs ordinary objects – imprinted in our cultural memory – onto the platform designated for elite art objects, through facsimiles, rather than metaphoric formulae. It’s a twist on the premise of the found object, which critiqued the aura of traditional art as it exposed the exhibition space as the main arbiter of cultural value. Here Emser constructs his found object, blurring the difference between fine art and craft, between hand made and factory built and between workshop and artist’s studio.

Emser’s respect for and facility with construction methods and craft traditions are readily apparent in subtle details of a finely tuned part of design history. His kinship with architecture and its collaborative legacy of aspirational form, as well as his responsiveness to geography and climatology remains intelligent and deliberative. His objects – small watercraft built from elaborate kits are selectively re-articulated to propel the work into new waters – pun intended.

Numerous moments in modern and contemporary art have been punctuated by technology, manufacturing and transportation and by our oft-idealized expectations of them. Like Emser’s abstract sculpture, the boat sustains an unusually light-footed connection to the drawing and the maquette (reflective of the artist’s youth). Their subtext is still Emser’s investment in discovery made palpable in his appetite for the diagram and hand-built construction. While his work has generally been more emblematic than practical, more responsive to the futuristic focus of early modernism, it was always embedded in studio rituals and the intricacies of design practice.

Today Emser is reinterpreting his cross-disciplinary interest and taking a swing at a more conceptual and yet more populist subject. Illinois is the perfect landscape for his sight lines. It has an unparalleled history and image of transportation and architecture. Our low horizons, rivers and Great Lakes give way to expansive skies and episodic weather where the architecture of small planes and boats are a persistent icon.