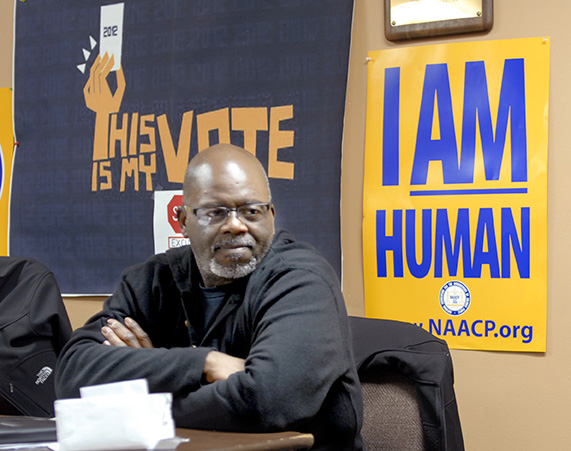

The Rev. Marvin Hightower, president of the Peoria NAACP, recognizes the nation’s destructive, misguided and punitive treatment of crack cocaine addicts and today’s different approach to opioid addicts most of whom are White, but Hightower says this is not a Black issue or a White issue. It’s a people issue, and a clean needle exchange program serving all people is urgently needed to combat the epidemic of addiction. (PHOTO BY CLARE HOWARD)

During a discussion about a clinic location in Peoria to supply clean, safe syringes to addicts illegally using drugs, Hightower said, “Data takes the emotion out. This is not a Black issue or a White issue. This is a people issue. This is a vitally needed service for a rampant problem.”

Peoria has some of the state’s highest rates of overdose deaths, HIV infections and sexually transmitted diseases.

A proposed clinic sponsored by the Jolt Foundation with private, state and federal funding is seeking to open a clinic in Peoria to supply clean needles, HIV testing, counseling about sexually transmitted diseases and other public health services. Similar clinics are successfully operating in nearly a dozen communities in Illinois.

In Peoria, community response has been mixed, but Hightower said, “I told Jolt, if I’m ever needed, I stand with them.”

Hightower recognizes that opioid addiction often has the connotation of targeting primarily affluent, White communities. Crack cocaine, on the other hand, was a blight that targeted African American communities, and the societal response was arrests, prison, destruction of families and communities. Now with opioid addiction, the response is to provide counseling, clean needle exchange sites and therapy.

Acknowledging that a vindictive and misguided response to crack cocaine addiction destroyed generations of African American families, Hightower said, “We can’t go back and correct problems in the past. We have to deal with today and the here and now.”

In the past, crack cocaine addiction was primarily among adults, however, children were also major victims when parents received long-term prison sentences and children went to foster care or into the homes of elderly grandparents.

Hightower said opioids are worse in the sense that an opioid addiction targets children and teenagers as well as grandparents, parents, the employed and the unemployed.

“Taking no action is not an option. At least we have to try,” he said.

Hightower said the board of the NAACP voted nearly unanimously to rent space in its offices on MacArthur Highway to the Jolt Foundation, but there was negative community reaction. The Foundation is now looking at a location on Northeast Adams Street near Spring Street.

Not far from Peoria, a safe needle exchange program has operated out of the Champaign-Urbana Public Health District for more than a decade, most of that time with Joe Trotter as a prevention specialist there.

He said the program has operated without controversy and accepts all clients regardless of residence. Some come from across state lines. Clients are 75 percent white and come from all socio-economic levels.

“We create a safe space where we help people until they are ready for treatment,” he said. “We don’t just throw needles out there. We have a whole range of other services.

“You have to be good at talking with people without being judgmental. These are not ‘junkies.’ That’s a term from another era. These are not people living on the streets. They are people caring for their families, doing their jobs, all the while battling this difficult addiction.”

Many people inadvertently become addicted to opioids because of pain medication following an accident or illness. Trotter said medical marijuana shows significant potential for treating pain without causing the addiction of opioids.

“We know coming for clean needles is not easy. We want to be as accessible as possible. Recovery from addiction is not easy. People feel like they are dying,” Trotter said, noting that timing is key and is based on each person’s situation. Successful needle exchange programs are ready to provide support and referrals to rehab services based on each client’s readiness.

According to research, if someone participates in a safe needle exchange program, they are five times as likely to enter rehab as people not using a safe needle exchange.

Jeffery Erdman, specialist with the Illinois Public Health Association, said for every $1 spent on a safe needle exchange program, there is $6 in savings to the healthcare system. HIV and Hep-C are both spread by sharing dirty needles.

Erdman said research also confirms there is no uptick in crime, drug use or dirty needles on the street with a designated safe needle exchange program.

“I have been in this field since 1992. I love this work, love public health,” he said.

These clinics are in all different kinds of neighborhoods including residential.

“These clinics become invisible,” he said. “HIV and Hep-C have been reduced by 70 percent in some communities with syringe exchange programs. I understand community concerns, but the negative stigma is undeserved.”

When he was governor of Indiana, Mike Pence outlawed clean syringe exchange programs. Following that decree, there were 181 HIV diagnoses in Scott County, Indiana, from Nov. 2014 to August 2015 among intravenous drug users, and 95 percent of those also had hepatitis C. Cost for treating hepatitis C is more than $30,000 per person. In September and October after the ban on clean syringe exchanges was lifted, there was not one HIV diagnosis.

Trotter, with the program in Champaign-Urbana, said “People don’t give up their basic right to healthcare once they become addicted.”

He said successful syringe exchange programs increase the likelihood of successful rehab.

“When Jeff Sessions says ‘just tough it out’ and stop using, that’s a naïve perception of drug addiction usually from people who don’t know and don’t understand,” Trotter said. “When someone actually knows someone dealing with this addiction and knows the research, that perception changes.”

Recent Comments