BILL KNIGHT

The United States was neutral for two years, but a pro-war movement led by powerful industrialists resulted in the U.S. declaring war in April 1917. That mobilized anti-war forces, including labor leaders, to resist, resulting in hundreds of people prosecuted and jailed for treason, including prominent union man Eugene Debs.

That’s one of the back stories in Yale Strom’s new, 97-minute documentary, “American Socialist: The Life and Times of Eugene Victor Debs,” released on video this month.

An Indiana-born man and five-time Socialist Party candidate for U.S. President, Debs gave his life to standing up to government for workers’ rights and free speech.

Contrary to shallow histories, World War I was a senseless slaughter (10 million died), a war involving no invasion but a callous “reboot” for Europe’s Great Powers – and a contributing factor to both Nazism and Stalinism. Many Americans objected to the nation’s involvement, and many were imprisoned or deported for voicing opposition.

Debs served time in federal prison, and so did two Peorians, according to records of the National Civil Liberties Union (forerunner of the American Civil Liberties Union).

In Peoria on May 9, 1918, Daniel Mahoney was sentenced to 18 months in prison for seditious remarks, and C.H. Kamann was sentenced to a three-year prison term and a fine of $5,000 for making disloyal comments.

“A Peoria history teacher, Kamann was dismissed by the school district and convicted under the Espionage Act, accused of telling his 12- to 15-year-old students that ‘getting the [German] Kaiser would not end the war,’” according to “Books, Not Bombs: Teaching Peace Since the Dawn of the Republic” (2010) by Charles Howlett and Ian Harris.

“This is a war of nations, and does not depend on getting anybody, whether the Kaiser, the President or the [Russian] Czar,” Kamann commented.

However, “pupils in his classes testified that he praised the Kaiser and criticized the United States in connection with the war,” according to a (Carbondale) Daily Free Press news story that day, which noted that Kamann was a former Peoria principal and ex-president of Illinois’ German-American Alliance.

As for Debs, there are ties to Peoria and Illinois.

A high school dropout, Debs had worked for railroad companies cleaning engines or cars, painting, and as a fireman; worked for a grocery while attending night school; and then returned to railroading as a member of the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen (BLF). There, he rose in the ranks and eventually edited its monthly magazine from 1881-1894, after which it was edited by W.S. Carter in Peoria before Carter went on to become the group’s national president from 1908-1919.

Also, Debs is recognized with an historical marker at the Old Courthouse and Sheriff’s House in Woodstock, Ill., where he was first jailed for six months after defying a court order to end the Pullman Strike of 1894. That installation last summer was controversial, marking not only his 1895 incarceration in the McHenry County Jail for “mail obstruction,” but for noting his devotion to socialism.

“You can see Debs as a labor leader; you can see him as a socialist,” said Woodstock Celebrates Inc. board member Kathleen Spaltro. “You could also reconceptualize Debs as an American whose constitutional freedoms were violated twice … and who stands for citizens pushing back.”

During Debs’ term in Woodstock, he read voraciously and emerged as a socialist, eventually co-founding the Social Democracy of America (1897), the Social Democratic Party of America (1898), and the Socialist Party of America (1901).

That Pullman Strike stemmed from the response by the American Railway Union (ARU), an early industrial union Debs helped establish, after workers there launched a walkout over pay cuts. Debs organized its workers and initiated a national boycott of trains with Pullman cars. The strike involved a quarter of a million workers in dozens of states.

Supposedly to keep the U.S. mail running, President Grover Cleveland used the U. S. Army against the strike, and court injunctions to halt the work stoppage were filed. Defended by Clarence Darrow before the U.S. Supreme Court, Debs was convicted of violating the injunctions and imprisoned.

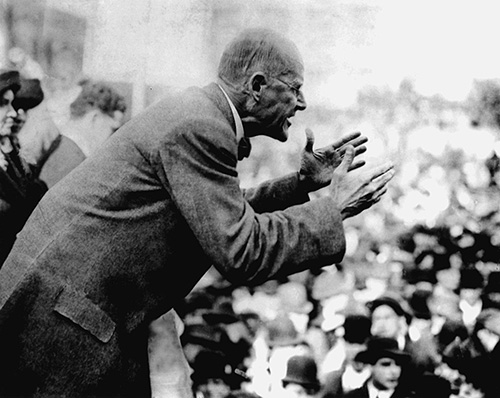

Union organizer and presidential candidate Eugene Debs speaking in Canton, Ohio, in 1918 against American involvement in World War I. Debs and many other Americans were imprisoned for voicing opposition to the war.

Years later, President Woodrow Wilson (a Democrat and racist former New Jersey Governor and Princeton University president) used the Espionage Act of 1917 as a bludgeon against dissent. Debs was arrested for speaking out against World War I’s draft, and, like Peorians Kamann and Mahoney, he was tried as a traitor in the summer of 1918.

At Debs’ sentencing, he said, “I never more fully comprehended than now the great struggle between the powers of greed on the one hand and upon the other the rising hosts of freedom. I can see the dawn of a better day of humanity. The people are awakening. In due course of time they will come into their own… . The cross is bending, midnight is passing, and joy cometh with the morning.”

His 10-year prison term was commuted three years later by Republican President Warren Harding, and upon Debs’ release from the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary (where he ran for President for the last time, receiving almost 1 million votes), prisoners cheered him, and when he arrived home in Indiana, he was welcomed by a crowd of about 50,000 well-wishers. He was nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize in 1924.

Incidentally, NCLU records show that Mahoney was one of 53 people whose sentences also were commuted (his to one year and one day, and he was released), and Kamann’s conviction eventually was overturned on appeal.

Another Illinois/Debs connection, sadly, is in Elmhurst, where in 1926 Debs became a patient at Lindlahr Sanitarium, where he died.

The movie, meanwhile, “offers so many piquant moments through visual documents and a vivid narrative that highlighting one or another becomes difficult,” wrote labor historian Paul Buhle. “Debs and the socialist movement did not fail the U.S.; quite the reverse. He saw – and the film is quite clear about this – the world emerging from war as brutal, the war’s unprecedented slaughter as normalized, and a terrifying sign of what lay ahead.”