PAUL KRAINAK

Designer, photographer and now hand-made book artist and printmaker Robert Rowe came to Bradley University from Marshall University in Huntington, W. Va., in 2000. During his 20 years in Huntington, Robert served as the head of graphic design and photography and also chaired the department before leaving for Peoria. In his tenure at Bradley, his studio production began to expand. He moved from focusing primarily on graphic design and photography to letterpress and book arts, something that has a significant history in nearby Chicago and in the Midwest. Last year he retired from teaching and was awarded professor emeritus status.

Now he devotes more time to his burgeoning studio practice and to local artists and writers who are eager to fuse images and texts in his workshops and at his Gold Quoin Press that he founded a few years ago.

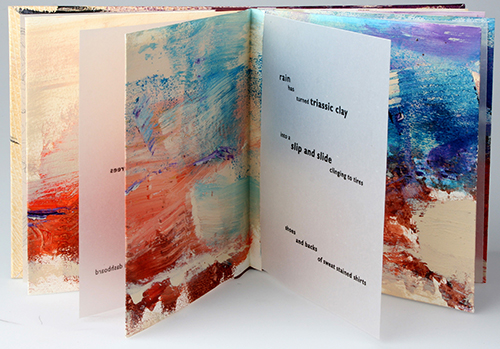

In Rowe’s hand-printed projects every skillful detail, every piece of material – ink, binding, paper in somatic play, competes for our attention. Some works contain a few discrete lines of text floating effortlessly in spaces between bold washes of ink. Other times they’re submerged in color, nearly illegible. Occasionally text bends with the arc of background brushwork or braces compositional angles, drawing lyrical and structural correspondences between language and music.

The issue of objectness in art stems from both visual and literary matrices. In narrative art, groundbreaking forms like concrete poetry, materialist filmmaking and formatting and cover design in modern novels, have expanded upon ideas such as “sign over signified” and “form follows function.” They’ve relaxed the restrictive formulas of figure/ground and the time-based logic of grammar. Yet, it requires the reader to collaborate, i.e. be an engaged reader, with the artist/author to reap the conceptual risks and rewards of structural change. The book form has proven particularly appropriate because it’s more suitable for juxtaposition and montage, and more operational than other narrative mediums. It’s the reader’s option to skip to the middle or the end and then back to the first chapter in a heartbeat. You can re-read a sentence, look up a word, write in the margins. Touch the page and the oil in your skin merges with paper and ink and vice versa. More than any other medium artist books require a broad measure of observation and contemplation.

Rowe’s work is nothing if not contemplative. He arranges texts in a way that moves beyond narrative, crafting it formally and conceptually. Text isn’t just integral, it’s elemental particularly when he’s addressing nature or the body. It may be the most critical component and given the artist’s expertise with typography and love of travel, it drives content.

Robert Rowe book “Onion Creek,” 6- by 6.5-inches. Materials are paste, paper, acrylic paint, letter press and electrostatic printing.

Rowe’s “Onion Creek” book is a distillation of a trip the artist took to the Utah desert a few years ago. Pages are filled with vivid and tactile paint passages and text that perform much larger than their actual dimensions. Rowe describes the site. “Onion Creek starts in the La Sal Mountains of Utah and descends to the Colorado River, going through fantastically shaped rock spires. The rugged unpaved road repeatedly drops and crosses the stream bed, which in summer can be completely dry crusted with a white rime of salt laced with arsenic, cadmium and selenium leached from the surrounding Jurassic rock.” The desert is one of the artist’s principal muses. The architecture and tactility of the book simulates his experience, and/or memory in deft, abbreviated phrases.

Rowe also travels in a complicated aesthetic territory, generating a self-reflexive sketch that beckons city-dwellers with a promise of intimacy and timelessness. These are notions that have been applied to the West since the beginning of the Republic. Rowe’s portrayal of dust and sweat, however, amends that legacy with tender, unadorned expressions of conservancy and respect.

1 comment for “Inland Art | Robert Rowe”

Recent Comments

I had the incredible privilege of studying under Mr. Rowe at Marshall University, and his talent, passion, and dedication to his craft left a lasting impression on me. It’s so inspiring to see his work being recognized and celebrated! His creativity and insight have influenced so many, and I’m grateful to have had the opportunity to learn from him. Looking forward to seeing what he creates next!