Volunteers at the food pantry at Bartonville Christian Church box up food to help provide for those in need across four townships.

PHOTO BY BILL KNIGHT

On Saturday, May 13, the morning will start slow for thousands of volunteers from coast to coast. At the USPS Persimmon Annex just south of the State Street Post Office, Cub Scouts from Pack 219 will meet, grab a snack, and wait for USPS trucks to start rolling in. Then the pace picks up for “Stamp Out Hunger.”

“The kids run out, help unload bags and bags of food, and start to separate glass from cans and so on,” says Wayne Cannon, a Scout leader and also director of the Peoria Area Food Bank.

“It’s pretty organized. Maybe organized chaos,” he adds, smiling.

Asked what he feels like at the end of the day, National Association of Letter Carriers (NALC) Branch 31 President Scott Haney, who helps coordinate the greater Peoria event, smiles and says, “Sore. Happy-tired.”

Stamp Out Hunger has been collecting for food banks and pantries for more than 25 years. NALC leads the effort, with involvement by the U.S. Postal Service, United Way Worldwide, United Food and Commercial Workers International Union, Kellogg Co., the National Rural Letter Carriers’ Association, CVS Health, the AFL-CIO and more — plus countless volunteers.

Days before May 13, Letter Carriers leave plastic bags for postal customers to hold nonperishable food for pickup. By the end of the day, Peoria’s North University USPS will have seen some 60 trucks bringing in tens of thousands of pounds of food, Haney said.

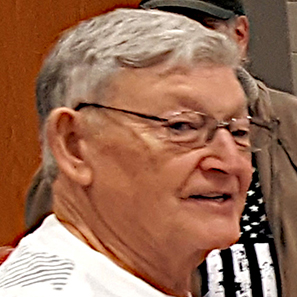

Local Letter Carriers president Scott Haney will help lead Stamp Out Hunger on May 13.

PHOTO BY BILL KNIGHT

People come together to help those in chronic need, folks who’ve hit a rough patch or families hurt when summer means no school nor school breakfasts or lunches. “There’s no ‘red’ or ‘blue,’ ” Haney explains. “It’s regular people helping regular people. Our employer helps, as do rural carriers and clerks and everyday people.”

Crunch time

It’s more timely than ever this year, as March saw cutbacks in the pandemic emergency allotment for individuals and households enrolled in the federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) in the 32 states that participated, triggering a cut of at least $95/month. The COVID assistance kept 4.2 million Americans out of poverty, according to the Urban Institute.

One of the country’s key social-safety programs, SNAP’s overall low-income households’ daily assistance dropped from about $9 to $6.10. Meanwhile, food prices went up considerably since the emergency relief took effect.

In Illinois, SNAP’s reduction will affect 1,058,837 households, according to the Food Research & Action Center, which adds that older adults at the minimum benefit level will be hurt the most — dealing with benefits dropping from $281/month to $23.

Slashing SNAP means some people for whatever real reason may face choices like buying food or paying their power bill.

Asked if agencies like his have concerns about the SNAP reductions, Cannon says yes — and no.

“Concerned? More? Hard to say,” he comments. “We still have difficulty believing the need out there.”

Across communities

The need is rural as well as urban, says a group of more than a dozen volunteers at the Bartonville Christian Church, where a food pantry serves four townships that include the communities of Bellevue, Glasford and Hanna City as well as Bartonville.

The back door of a metal building adjacent to the brick church on Pfeiffer Road leads to a roomy space inside, where long folding tables are filled with banana boxes overflowing with pasta, peanut butter, tomato sauce, bread and more. Operating for decades, BCC’s pantry helped 28 families weekly in 2012, records show. This January, it assisted 94 families.

Recipients are eligible for boxes of canned fruits and vegetables, nonperishable/boxed food, bread, etc., once a month, says Bartonville volunteer Connie Malson.

The attitude is lending a hand without passing judgment

“They’re people dealing with some kind of hardship,” Malson says. “It could be your next-door neighbor. You don’t know people’s circumstances.”

Another longtime volunteer, Terry Post — from nearby St. Anthony’s Catholic Church, which recently sent more than 560 pounds of food — says all the people who pitch in to help don’t do it for a reward, exactly.

“Stamp Out Hunger bolsters pantries’ operations,” he says. “Refilling pantries.

“There’s not really a sense of accomplishment,” he says, calling 13 people to gather at tables stacked with food. “It’s more like if we’re able to be here, we want to be here. I guess that’s fulfilling.”

About seven miles northeast, a single-story. cinder-block building on McBean houses the Peoria Area Food Bank’s modest offices and storage area. Outside, a cart and handful of wood pallets stand near a loading dock. In its attached warehouse, neatly stacked on tall shelves, Gaylord corrugated cardboard boxes are filled with food ready for sorting and shipping.

Sourcing

Since 2018, Cannon has led the Peoria Area Food Bank, which has a staff of six and five 24-foot box trucks and a van to provide food to 83 pantries and four soup kitchens in Peoria, Tazewell and Mason counties.

Last year, the food bank, part of Peoria Citizens Committeee for Economic Opportinity (PCCEO), collected 2.4 million pounds of food, or about 2.7 million meals, Cannon says.

“Stamp Out Hunger is a major food drive,” he says. “We collect anywhere from 30,000 to 60,000 pounds just that day.”

But numbers aren’t the whole story, Cannon says, noting a growing change in food banks’ philosophy.

“Our mission is to reduce the need, to help people be self-sufficient,” he says. “We want people to know about nutrition, too, about food waste, and how to stretch dollars to buy good food instead of soft drinks and processed food.”

He said operations like his don’t look to grow and go along with more need on the short-term. It’s as if fire departments added more fire-fighting equipment but ignored preventive measures such as smoke alarms. “Long-term, we want to be part of dealing with root causes of people with food insecurity,” Cannon says.

Cannon, Haney and Malson all stressed that the food all stays local — “to Creve Coeur and Germantown Hills as well as Peoria,” Cannon adds.

It’s not necessary to go out and buy extra food to donate to Stamp Out Hunger,” he continues. “Just go to your cupboard and see what’s there and share some.”

And people interested in personally volunteering should look nearby, he suggests: “Start at your local food pantry.”