Sherry Cannon reads one of the markers put up throughout Montgomery by the Alabama Historical Commission. (PHOTO BY JILL FRIEDMAN FOR COMMUNITY WORD)

Montgomery is a city of contradictions. It is known as the Cradle of the Confederacy as well as the birthplace of the Civil Rights Movement that was born from the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

The city has markers throughout the town square that tell its story. There is a sanitized history told by the Alabama Historical Society markers and the real history told by the Equal Justice Initiative.

Civil Rights attorney Bryan Stevenson founded the Equal Justice Initiative to confront racial injustice and advocate for equality. Stevenson and the EJI created two new museums that opened in April –– The Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice.

Pam Adams, former reporter at the Journal Star, and I had been warned not to visit both museums on the same day. It’s too emotionally draining.

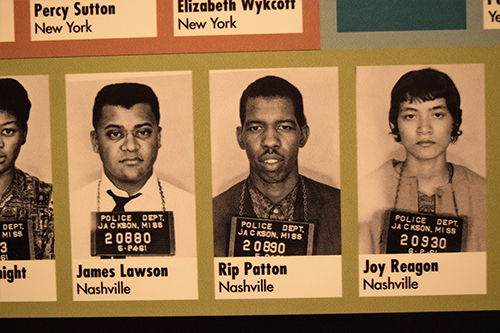

Rip Patton, one of the original Freedom Riders, speaks with Sherry Cannon and Pam Adams, right, about the attack by a white mob against him and other Civil Rights activists in 1961. Patton and the others were trying to integrate inter-state public transportation. (PHOTO BY JILL FRIEDMAN FOR COMMUNITY WORD)

Our first stop in Montgomery was the Freedom Riders Museum. This is the site of the Greyhound Bus Station where 20 civil rights activist were assaulted while attempting to ride from Washington, D.C., to New Orleans in an effort to integrate inter-state public transportation. On Mother’s Day, May 14, 1961, an angry mob of white people blocked their bus, slashed the tires, broke out the windows and set the bus on fire. John Lewis, a student leader, and two other men were beaten unconscious.

One of the original Freedom Riders was at the museum the day we visited. Rip Patton, a youngish 78-year-old man, generously took pictures with us and spent an hour sharing memories of the movement. Like those who have fought in war, Patton said there are things that happened that he never talks about, even with those he worked with in the movement. Amazingly, he has no anger or bitterness. For every protest he engaged in, he quoted a scripture from the Bible that served as his motivation.

Rip Patton was one of the original Freedom Riders who were attacked in 1961 by an angry mob of white people. Patton and other Freedom Riders including the Rev. C.T. Vivian, a former Peorian, were targeted because of their efforts to accelerate the slow pace of integration in the United States. Many Black and white Americans were arrested in the South when they exercised their legal rights. (PHOTO BY JILL FRIEDMAN FOR COMMUNITY WORD)

We made our first visit to the Legacy Museum the following morning. EJI spent a decade conducting research to gather the history of racial injustice and the narratives that tell the stories of victims.

The museum opened on April 26, 2018, on a site that previously warehoused enslaved Black people. It is located midway between the slave market and the river dock and train station where tens of thousands of enslaved people were sold during the height of the domestic slave trade.

Upon entering the museum, through amazing technology, visitors hear firsthand accounts by enslaved people talking about their trauma being captured, held in prison and sold away from families. They were held in dungeons, pens, jails and warehouses. Enslaved Black people were warehoused in the same place as livestock and cattle.

“Walk with me Lord, walk with me. Walk with me Lord, walk with me. While I’m on this tedious journey, I want Jesus to walk with me!”

This song is sung at an exhibit of a life-size hologram of an old woman. She is one of several holograms who tell their story of being captured, of their mistreatment and their hope for a better day.

Throughout the museum, the history of slavery is told. In 1619, the first enslaved people were brought from Africa to Jamestown, Va. International slave trading was banned in 1808 in the United States.

More than 12 million Africans were kidnapped and more than 2 million died at sea.

However, America continued slavery another 57 years, using the narrative that people of African descent were inferior to justify this cruel and inhumane practice.

During domestic slavery, enslaved people often were forced to walk more than 1,000 miles from Georgia to Montgomery, a four-month journey.

Rail lines were constructed for faster transportation. Slave labor connected Montgomery’s rail lines to West Point, Ga., and lines extended to the upper South.

Alabama had one of the largest populations of enslaved people. From 1810-1860 Alabama’s slavery population grew from 40,000 to more than 435,000. Black people comprised two-thirds of Montgomery County’s population.

In 1833, Alabama banned free Black people from living in the state. If emancipated people returned to the state and were caught, they would be arrested and sold to the highest bidder. The money from the sale would go into local government coffers.

On the walls of the museum are stories of people sold into domestic slavery. R. Saunders was one of five siblings sold and separated after the death of their master. M. Grady was sold away from his wife, and when he asked to shake his wife’s hand before they were separated, he was told no.

Then there is the story of a young boy, who was chained to an older man. The young boy says this older man was the only kind person he had ever encountered in his short life. The older man carried the chains in a way that gave him the brunt of the chains’ weight and gave the boy relief.

Moving through the museum, you go from slavery to emancipation.

Thousands of emancipated Black people were killed in the first weeks, months and years by white southerners angry and bitter over the end of slavery and hostile to the idea of racial equality, according to historian Leon F. Litwack.

One of the narratives in the museum after slavery is from Fountain Hughes. Mr. Hughes lived to be 101 years old. He was born into slavery and was emancipated in 1865 after the Civil War. His grandfather was enslaved by Thomas Jefferson and lived to be 115 years old.

Mr. Hughes is recorded as saying Black people were treated no better than dogs, and often a dog was treated better than an enslaved Black person, and he would have killed himself before being enslaved again.

From 1877 to 1950, 4,400 lynchings of African Americans have been documented. These heinous acts were committed by groups of two to mobs of 10,000 white people.

A section in the museum has shelves of mason jars containing soil from the different lynching sites. Each jar is labeled with the victim’s name, date of his death and county where the lynching occurred.

In an alcove, next to the mason jars, you can watch videos that tells the stories of victims of lynching.

Along another wall in this section of the museum are the names of lynching victims and the reason they were lynched. A few samples of the hundreds of documented lynchings are:

- Robert Mallard was lynched in 1948 in Lyons, Ga., for voting.

- Minister Arthur St. Clair was lynched in 1877 in Brooksville, Fla., for performing a wedding ceremony between a Black man and a white woman.

- John Hartfield was lynched in 1919 in Ellisville, Miss., for allegedly having a white girlfriend. The local newspaper advertised the lynching, and up to 10,000 white men, women and children came to witness this heinous act. He was hung, shot, burned alive, and his lifeless body was tied to a horse and dragged through the town.

As you continue through the museum, you see how slavery, Jim Crow and mass incarcerations are linked. The same way a narrative of inferiority was given as a reason to enslave African people, a presumption of guilt and being dangerous has been assigned to African-Americans.

Beginning in 1940 court-ordered execution became America’s solution to the bad optics of lynching. From 1927-1976, 82 percent of people legally executed in Alabama were African-Americans.

For every nine persons executed in the United States since 1976, one person on death row has been exonerated. There have been 160 people on death row proven to be innocent of the crime they were convicted of.

In 1972, there were 300,000 people in U.S. prisons. Today there are 2.3 million people incarcerated.

Bryan Stevenson began defending death row inmates about 30 years ago. One wall of the museum is filled with letters EJI received from imprisoned people asking for help.

One letter that stayed with me is from a man named Vernon. Vernon was on death row, and he watched another man walk past his cell to be executed. Vernon wrote, “As he walked pass my cell with his head bowed low, a guard and a priest silently walking at his elbows; without looking up and tears rolling down his cheeks, I heard him ask, will there be any handcuffs in Heaven and chains for my feet?”

Innocent Black people are seven times more likely to be falsely convicted of murder than white people. In 2015, police killed an average of two unarmed Black people each week.

A study done in 2017 by Georgetown Law Center on poverty and inequality reveals astonishing levels of bias against Black girls.

- Black girls are seen as older than white girls of the same age.

- Black girls are assumed to need less nurturing, protection and support than white girls.

- Black girls are five times more likely to be suspended from school than white girls, and they are suspended two times more often than white boys.

Pam and I returned a second day to the Legacy Museum. Following the advice of Rip Patton, we experienced the museum both days independent of each other. It is not a space where you want to have dialogue with anyone. Processing the inhumanity that has been endured by people of African descent was difficult.

EJI has done an amazing job presenting this information in multiple formats. Unable to read one more letter of pain and suffering or watch one more video narrative, I sought refuge in the one space that was safe.

Near the exit of the museum is a display that I call “the wall of heroes.” On the wall are the names of dozens of African-Americans who, in spite of all odds, excelled to become trailblazers in their fields or civil rights pioneers who looked hate and fear in the face and accomplished amazing deeds in the fight for equality and justice.

These amazing people are owed a debt of gratitude by this country. They not only proved it’s a lie and a myth that descendants of Africa are inferior; but they also lived out Romans 5:3 “Because we know that suffering produces perseverance, character and hope. And hope does not disappoint us because God has poured out his love into our hearts by the Holy Spirit whom he has given us.”

Pam and I talked to everyone we encountered from our Uber drivers, to a homeless man who became our unofficial historian. Everyone was willing to engage with us and share their thoughts on the past Montgomery and today’s Montgomery.

One of my most interesting conversations was with Mr. Henry Pew. He is a Blues singer and a musician. Every Saturday at midnight in a club called the Underground, Mr. Pew sings and plays keyboard. Luckily, the Underground was directly across the street from our hotel.

After taking a nap, Pam and I went to the Underground and spent a couple of hours before flying out at 7:30 a.m. To our good fortune, we were the first customers to arrive and had a chance to chat with Mr. Pew. He had performed in this same club during segregation. Back then he was not allowed to come in the front door, and he had to sing to an all-white audience with his back turned to them.

Today, Mr. Pew owns the entire building. The clientele this night was still predominantly white. Not only did he not perform with his back to the audience, but every woman in the place was called up by Mr. Pew to sit on a stool while he sang a song to her.

After touring Montgomery, the one thing I know for sure is the abiding faith and strength Black people possess and have demonstrated through slavery, Jim Crow and even today through mass incarceration.

Though it was challenging, I believe as EJI believes, that it is necessary to face this ugly part of American history. The history we won’t face is the history we’re likely to repeat.