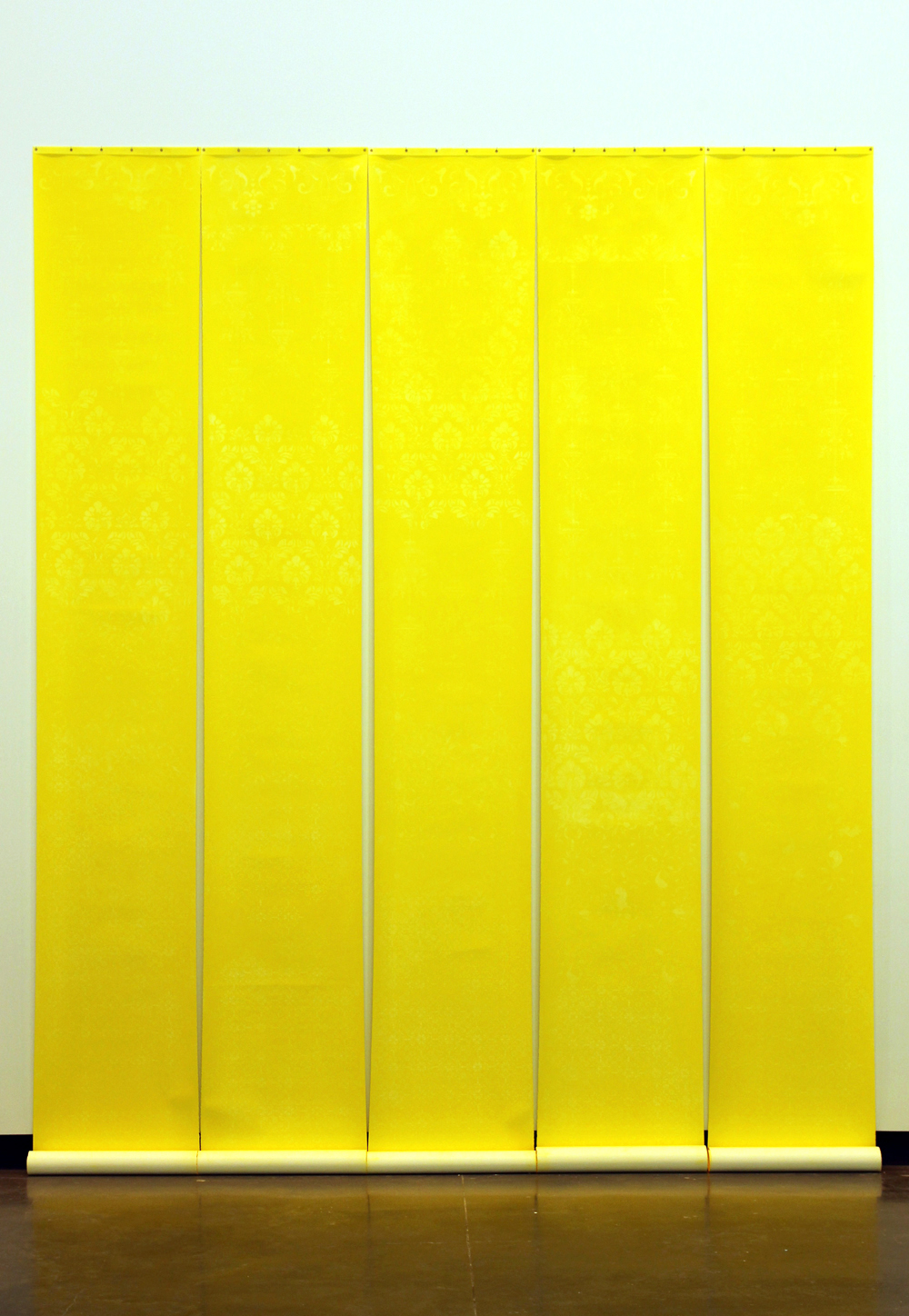

Leslie Bellavance, “Vicious Influence: Homage to Charlotte Perkins Gilman” 2003 – 2013, Soft Pastel on Paper, 15 feet x 14 feet.

PAUL KRAINAK

In 1995, Bellavance had one-person shows at the Milwaukee Art Museum and the Gallery 400 at the University of Illinois. She continued showing with photography-based work as well as collaborative installation and mixed media projects in various venues over the following decade. Then came a 16-year studio hiatus as a university administrator. The curatorial and operational processes of alternative spaces and the attendant writing and fundraising that was once a requirement of a serious artist, served her extraordinarily well as graduate coordinator and then interim associate dean in Milwaukee, (UWM). That appointment matched other academic programs’ adaptation of new genres emerging from alternative projects like those on Hubbard Street. Photography and video were driving forces in the ’80s, but so were art market critique, localism, and feminist theory. Bellavance took that knowledge to positions at James Madison University where she was Director of the School of Art & Design, Dean of the School of Art & Design at Alfred University, and finally as President of Kendall College of Art & Design in Grand Rapids, Michigan. She retired from Kendall last year and is now absorbed in reclaiming her quiescent studio practice.

PK: Leslie it’s great to talk, despite only having the chance to see your work virtually, like so many artists work, over the last year. With COVID-19 a national audience is basically a virtual audience. Studio artists across the country are feeling claustrophobic, but for inland artists producing an autonomous context for work and identifying non-traditional spaces for creative production and revised aesthetics is business as usual.

LB: Yes, seeing art, and experiencing the performing arts, has been challenging this year. I have participated in some innovative approaches to virtual presentations and discussions about art that have been more inclusive because they are virtual.

PK: After 16 years of administrative heavy-lifting in higher education, how does the studio feel, especially moving into a medium and imagery that I’m less familiar with?

LB: It feels like an amazing gift to reconnect to making art. While the work I did in administrative leadership certainly involved problem solving and creativity, it was a different way of thinking. Working in the studio is always about continuous invention, so the idea that I am starting from a new position in how I work with materials and content is something I expected and desired.

As for working in a new media, I have always worked in a variety of media. Mostly it’s been photography, drawing and painting, but also mixed media installation and book forms.

PK: Are the patterns on your new color studies a reference to Bauhaus textile design?

LB: Patterns in the decorative arts in general are on my mind as I work on these new drawings and paintings; anything from Bauhaus textiles, mid-century modern and contemporary textiles, vernacular patterns, but also color field paintings and modernist abstraction. I have used these kinds of patterns in previous work for a variety of reasons. The patterns and color fields I am using now are simple and intended as a vehicle for the observed atmospheric colors in natural environments and landscapes. I am currently working on this new project in its infancy. I fully anticipate that the conceptual interrogation that I engaged in my previous work will be part of this new work too. At the same time I wish to liberate the work from too much to carry.

PK: You mention landscape as a source of your color. Does color, or the structure, come from architectural as well? Michigan, Wisconsin and Illinois, where you have spent part of your career, have such a complex art and design legacy?

LB: A key conceptual underpinning to my career-long interest in the landscape as a visual and narrative form is my resistance to the dichotomous relationships of opposites such as wild/tame, wilderness/cultivated, nature/human, women/men, animal/plant, animate/inanimate, etc., and how these play out in actual, imaginary, psychological and conventional notions of figure/ground relationships and subjectivity. That’s a complicated way of saying I like to explore the permeability of categories of things or ideas that seem, or are accepted as, different from one another.

Nevertheless, living in Michigan during this particular point in history has made me more sensitive to the results of a world-view that sees nature as culture’s playground and industry’s resource.

Since reading it in my first year in Michigan, Annie Proulx’s novel Barkskins has influenced my thinking enormously. A portion of the novel addresses the deforestation of Michigan in the 19th century. When asked in an interview who the protagonist of the novel is the author stated it was the forest. This resonated for me. Even though the “story” takes the familiar form of a multi-generational historic human family epic, it is not. It is a narrative reversal of the traditional dichotomous relation of figure/ground.

I try to keep these ideas in mind as I work on my humble observations of color in the oak forest that surrounds my home on the outskirts of Grand Rapids in order to keep open the possibilities of what I might find out.

Recent Comments