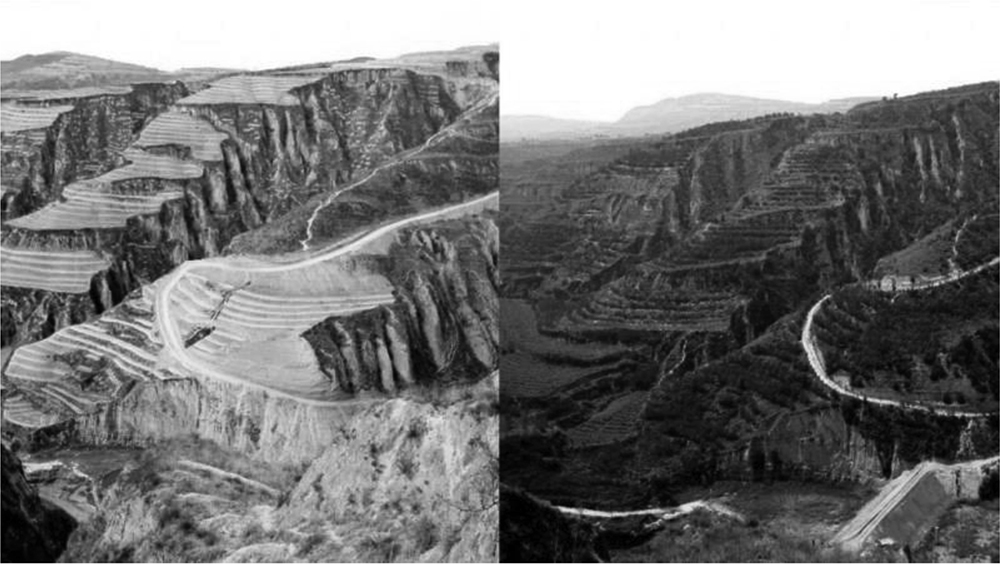

Jixian County before restoration in 2002, on left, and after restoration in 2005. (Image from World Bank Institute)

WILLIAM RAU

The “pulling” stage can unfold simultaneously with the move to a fossil-free economy. Indeed, a growing number of people are already working on carbon sequestration by regenerating depleted farmland and replanting once great forests. Both trees and soils absorb large quantities of carbon because photosynthesis draws CO2 from the air with plants and trees storing it in soil and biomass.

There are about 1 billion acres of thoroughly degraded agricultural land that has been abandoned. According to Paul Hawken in “Drawdown,” restoration of only 40% of this land would remove about 14 gigatons of atmospheric CO2 while generating a return of $1 trillion by 2050 for an upfront cost of $72 billion. Transforming another 1 billion acres of conventional agriculture to organic, regenerative farming would draw down 23 gigatons of CO2. Finally, the Earth has enough space to replant about 2 billion acres in forestland. If a half trillion of the right trees are planted in the right places, they would eventually store 200 gigatons of carbon, or about 25% of current atmospheric CO2 (Buis 2019).

A textbook example of large-scale ecological restoration involves the Loess Plateau, 300 miles west of Beijing. Once covered by forests and grasslands, this Texas-sized region was the ancestral home of the Han, China’s dominant ethnic group. Loess soil is fertile and farming in China began on the plateau. Loess soil is very fine, however, and considered “the most erodible soil on earth.” The Yellow River is, well, yellow, because of the large amounts of wind-and-rain-swept Loess sediments it carries away.

Declining soil fertility and yields forced Loess farmers to plant crops on steep slopes. Others turned to sheep and goats whose grazing left the plateau almost totally denuded. Heavy rains completed the destruction by sweeping away enough barren soil to moonscape the plateau. Floods, sandstorms, and desertification compounded the misery of farm families who relied on a grain subsidy because they could no longer feed themselves.

The Chinese government and the World Bank targeted the cycle of ecological destruction and immiseration with a “Grain for Green” Program. Rather than giving farm families a grain subsidy, they would pay them to turn the plateau green again. One crucial change granted farmers 30- to 70-year land tenure contracts, the de facto equivalent of transferring land ownership from the government to farmers. Parallel initiatives involved efforts to ban free-range grazing of animals, cutting trees and planting crops on slopes.

So, did this grand experiment succeed or fail? My June column will examine the outcomes.

References

Buckingham, Kathleen. 2016. Beyond Trees: Restoration lessons from China’s Loess Plateau. ANU Press; http://press-files.anu.edu.au/downloads/press/n1906/pdf/ch16.pdf

Buis, Alan. 2019 (Nov 7). Examining the Viability of Planting Trees to Help Mitigate Climate Change. NASA; https://climate.nasa.gov/news/2927/examining-the-viability-of-planting-trees-to-help-mitigate-climate-change/

Liu, John D. 2009. Hope in a changing climate. YouTube; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bLdNhZ6kAzo

Xie, Mei, et al. 2010. Rehabilitating a Degraded Watershed. World Bank Institute; https://www.researchgate.net/publication/236027728_Xie_et_al_Rehabilitating_a_degraded_watershed