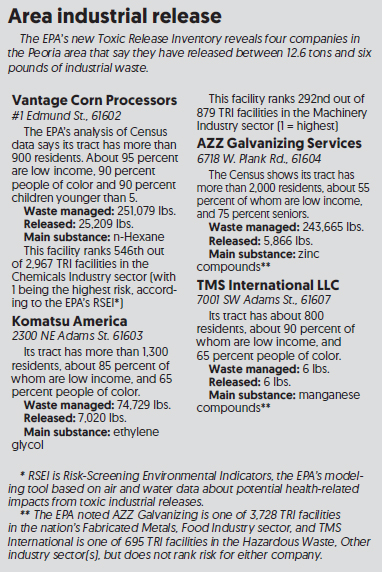

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s new Toxic Release Inventory shows companies’ data on industrial waste last year, and of all of Peoria’s zip codes, four have businesses that say they released between 12.6 tons to six pounds.

Metro Peoria has 33 “TRI facilities,” says the EPA, which administers the annual reports of data provided by the companies themselves under the Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act, which was passed in 1986.

The sites are in mostly low-income neighborhoods, and there’s been little public outcry from residents about harmful substances in their midst. Objections to the proximity of some business or government plans —protests dubbed NIMBY, for “Not In My Back Yard” — have ranged from disapproval of a port at Chillicothe’s riverfront to opposition to changes in parks or proposals for subsidized housing.

Thousands of people live near these TRI sites, but there’s no indication of “environmental justice” concerns.

Tonyisha Harris

“Environmental justice sets out to remove qualifiers such as race, ethnicity, or socioeconomic status from being a predictor of pollution and toxic development,” she told the Community Word. “Oftentimes, these communities contribute the least to pollution but bear the burden of its effects.

“Racist policies like redlining and lax environmental enforcement or regulation allow for polluting industries to be concentrated in low-income communities,” she added.

The lack of concern may be due to residents moving to such neighborhoods after the factories were there, possibly contributing to lower property values and making homes more affordable for the less fortunate. Other reasons for a begrudging acceptance are a lack of local organizing of residents who may be worried or economic concerns prioritized over public health.

“It depends on the community and the type of polluter,” Harris said. “Some coal communities may not fight back against a coal-fired power plant because it’s the primary source of income or jobs and contributes significantly to property-tax revenue. In these cases, the plant is the economic stimulator for the community and its removal would be far-reaching.”

Also, acquiescence might be because most such sites have existed for decades with no apparent problems, which can lead to tolerating risk.

Still, risk remains.

Local releases of toxic material have been controlled through regulated emissions or waste disposal.

Regardless, potential health effects of uncontrolled releases could be substantial. For example, the main substances released by these four sites are n-Hexane, ethylene glycol, zinc compounds, and manganese compounds. The EPA summarizes their dangers thusly: n-Hexane — neurological; ethylene glycol — developmental, renal, respiratory; zinc compounds — hematological, reproductive; and manganese compounds — neurological.

Details:

- n-Hexane is an irritant to eyes and skin, a cause of Central Nervous System depression, and can lead to dizziness, headaches, nausea and respiratory irritation, according to the National Library of Medicine, which also addresses

- ethylene glycol, a substance that also can cause “CNS depression (coma, hypotonia, eventually cerebral edema),” and renal failure;

- “large amounts of zinc can be harmful,” reports the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, causing stomach cramps, anemia and changes in cholesterol levels; and

- “exposure to manganese … can damage the lungs, liver and kidneys,” warns the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Manganese fumes can lead to a neurological condition, manganism, with symptoms similar to Parkinson’s disease.

Elsewhere, “communities do fight back against polluters,” Harris said. “Chicago has seen wins in this arena, such as the ban against pet coke (petroleum coke) or the delay of the General Irons permit (for its scrap-metal shredding operation). Communities are either not given the opportunity to weigh in on developments in their community and learn about the polluting industry once it’s approved, or the public-comment period is often symbolic and community concerns aren’t seriously considered in the permit approval process.”