For many Floridians, melting polar glaciers means too much water, rising sea levels, and eventual relocation. For many Peruvians, melting Andes glaciers means torrential spring floods, summer water shortages, and rivers — major sources of drinking water — possibly running dry during the summer. Lima, for example, receives one-third-inch of rain annually and must rely on three small, glacier-fed rivers for 80% of its water supplies.

These rivers are not faring well. Glaciers in Peru’s Andes are giant river-water batteries; warming dry-season temperatures providing steady flows of glacial melt for rivers through the summer. Peruvian pilgrims once honored glaciers by carrying chunks of ice, believed to possess healing powers, to villagers below. No longer. The glaciers have become “sick,” Peruvian highlanders say, and they don’t want to cause harm (Jonathan Moens 2020).

Highlanders don’t need weathermen to know which way the glaciers are going. They are going straight up the sides of the Andes.

Andes glaciers have lost three feet of thickness each year since 2000 and 40% of their areal coverage since 1970. Driving the change is a gradual shift from glacier-sustaining snowfall to glacier-dissolving rainfall. Additionally, the wet season has shortened while precipitation remains steady resulting in more intense wet-season rains and flash floods followed by longer, drier summers. As a result, Lima cannot provide 8 million residents with 24/7 summer water service while 1.5 million slum dwellers receive no service at all.

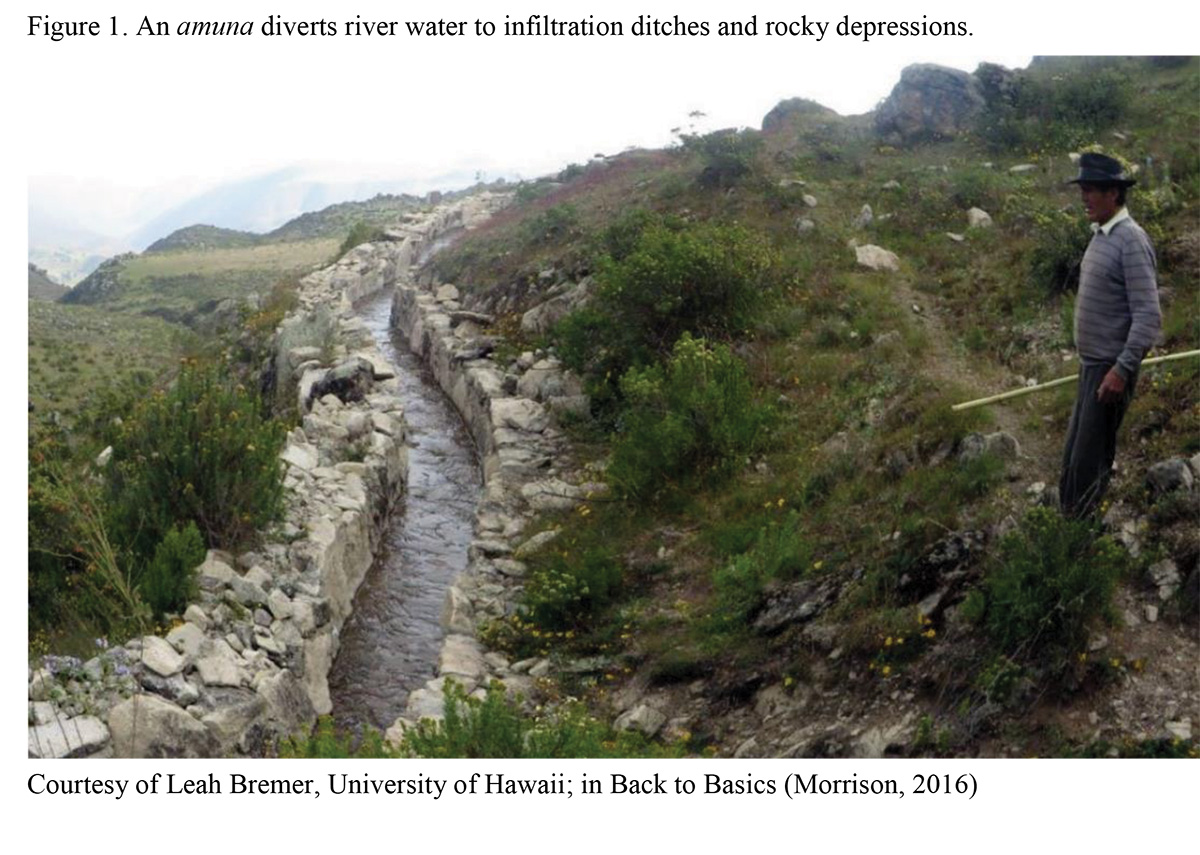

Peru is building expensive reservoirs and much more expensive desalination plants to eliminate water shortages. It is also returning to a 1,400-year-old water storage technology: the amunas (“retain” in Quecha). Amunas are water-tight, stone-lined channels that divert river water across mountain slopes to infiltration ditches or rocky depressions (see below). Absorbed into the soil, diverted water recharges the water table. As groundwater moves slowly downhill, it resurfaces in springs and ponds in the highlands weeks to months later while continuing on to seep into rivers, sometimes eight months later. Soil also functions as a water battery.

Other green solutions include moving to rotational grazing and restoring wetlands converted to pasture. Overgrazing of Peru’s native, puna grasslands has degraded their sponge-like, water-retaining ability. Unlike alpaca, whose padded feet and bite-sized nibbling left grasses intact, cattle pull out puna grass by the roots, thus leaving soil bare, while their weight and hooves compact soil. In short, restored grasslands turn lots of rain into groundwater.

These nature-based solutions require only one-tenth to one-hundredth of the cost of reservoirs and desalination plants, and, if fully employed, could meet 90% of Lima’s water shortage, which is why its water utility is quickly increasing investments in amunas and grassland restoration. Ancient technology can help fix Peru’s water woes — if the gods are kind.

The gods were not kind to Peru’s Moche civilization in the Fifth Century. Also located on the bone dry coast, the Moche relied on a sophisticated water diversion system until a mega El Nino hit them with 30 years of flooding and then 30 years of drought. Many Moche moved inland where water was available.

Different glaciers, different fates. In the future many Floridians will have to move to higher ground because of too much water while many Peruvians may have to move to higher ground because of too little water.

Further Reading

Gammie, Gena & Bert De Bievre. 2015 (Apr 10). Assessing Green Interventions for the Water Supply of Lima, Peru. Forest Trends; https://www.forest-trends.org/publications/assessing-green-interventions-for-the-water-supply-of-lima-peru-2/

Gies, Erica. 2021 (May 18). Why Peru is reviving a pre-Incan technology for water. BBC; https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20210510-perus-urgent-search-for-slow-water?zephr-modal-register

Moens, Jonathan. 2020 (Jan 30). Andes Meltdown: New Insights Into Rapidly Retreating Glaciers. Yale University; https://e360.yale.edu/features/andes-meltdown-new-insights-into-rapidly-retreating-glaciers

Morrison, Jim. 2016 (Aug 1). Back to Basics: Saving Water the Old-Fashioned Way. Smithsonian Magazine; https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/saving-water-old-fashioned-way-180959917/

Ochoa-Tocachi, Boris F., et al. 2019 (July). Potential contributions of pre-Inca infiltration infrastructure to Andean water security. Nature Sustainability; https://www.nature.com/articles/s41893-019-0307-1

Tegel, Simeone. 2022 (Dec 12). Parched Peru is restoring pre-Incan dikes to solve its water problem. Washington Post; https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2022/12/12/peru-lima-water-shortage-amunas/